Bitcoin & Crypto | Monetary Policy & Inflation

Bitcoin & Crypto | Monetary Policy & Inflation

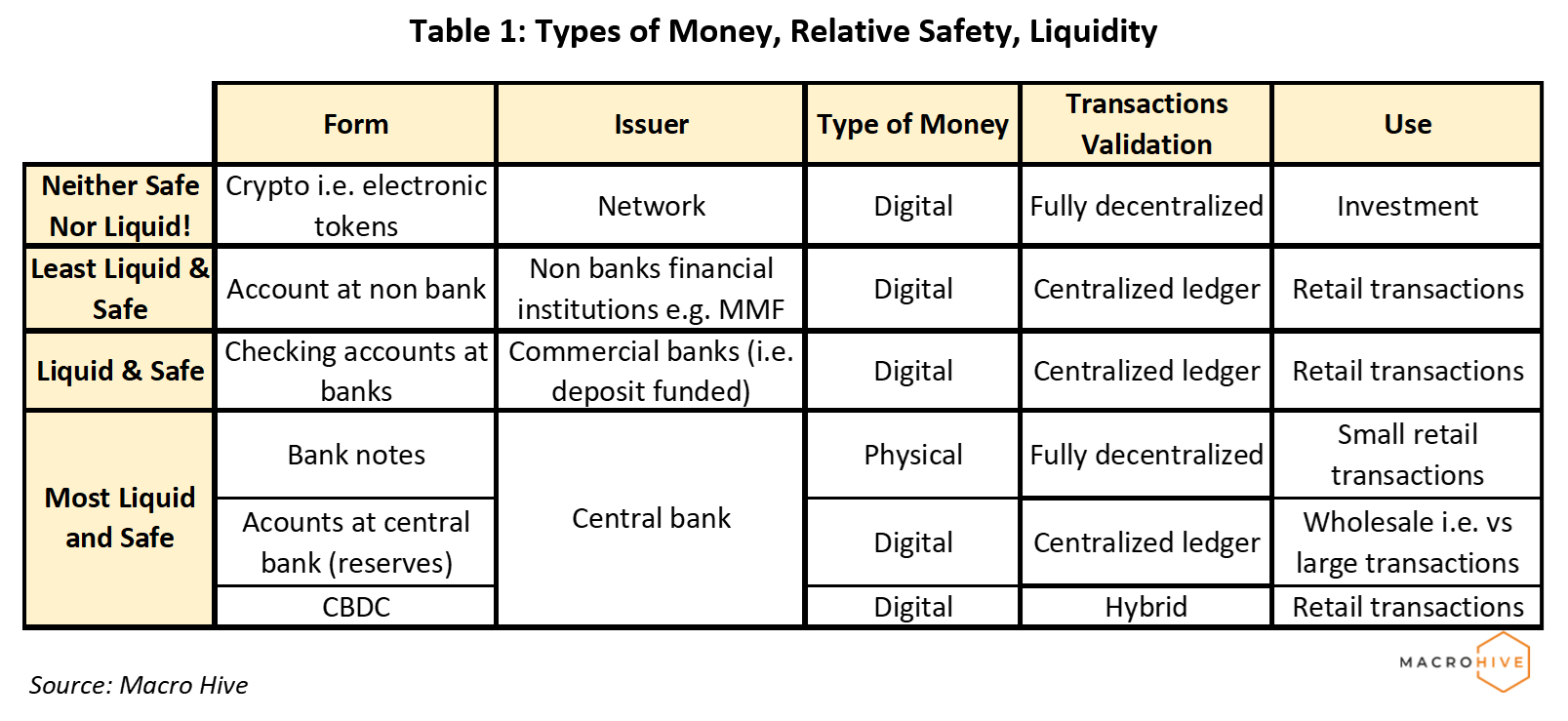

Central bank money has been around for a long time as physical banknotes and commercial bank deposits, also called reserves (Table 1). So has digital money, which is money stored or exchanged on computer systems. But central bank money is traditionally available to the non-bank public only as physical notes, which restricts its use to small retail transactions.

Central bank digital currency (CBDC) is a new kind of virtual fiat currency. It would make central banks’ digital money available to households and businesses, enabling its use in retail transactions.

The key difference between money issued by central banks and by commercial banks is that the former is safer and more liquid because it is legal tender money. That means any creditor is legally obligated to accept it for the repayment of any debt (it is slightly different to fiat money).

By contrast, a very small (but non-zero) risk exists that commercial banks default and therefore the money they have issued – our checking accounts – becomes worthless.

This is a huge deal. If I could hold my savings at the Federal Reserve (or a representative financial institution) while getting the same interest rate and convenience (especially with money transfers) as with my commercial bank account, I would transfer my savings to the Fed immediately. And so would millions of US depositors.

That means CBDC could become formidable competitors to commercial bank money, i.e., deposits.

Central banks typically have a cosy relationship with commercial banks and tend to protect them from competition. They do this partly because they view banking competition as detrimental to financial stability. Why, then, are central banks considering competing with commercial banks?

Nine countries have already launched a CBDC (the Bahamas, seven Eastern Caribbean countries and Nigeria). Meanwhile, 14 have CBDC pilots underway, and 57 are in the research and development (R&D) phase (the Atlantic Council has a nice dashboard). Most developed economies are in R&D except Sweden, which has already launched a pilot. The US is a laggard, only recently publishing a concept paper on a CBDC’s meaning for the domestic payments system.

The emergence of CBDCs reflects two key factors: ease of issuance and benefit.

First is the decentralized ledger technology (DLT) revolution has made it easier to issue CBDC. DLT is a set of infrastructure and protocols that allow simultaneous access, record updating and validation across a network – the technology behind cryptocurrencies. DLT allows central banks to issue tokens, equivalent to digital banknotes (see below), to the public. The alternative would be for central banks to issue deposits to the public, for which they have neither expertise nor capability.

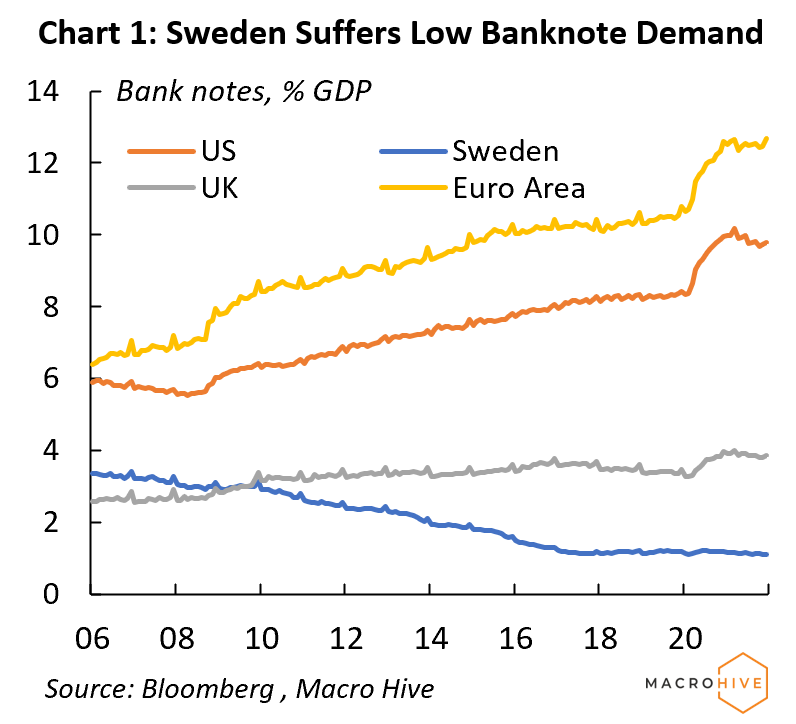

Second, central banks see considerable benefits to launching CBDC. In some countries, cash use has declined, depriving central banks of revenues. The advanced economy with the most advanced CBDC project, Sweden, has the lowest banknote use in the world, about 1% of GDP. By contrast, demand for dollar and euro banknotes has been rising. This could explain why the US has expressed limited interest in launching a CBDC so far (Chart 1).

A CBDC could also create new and more powerful instruments for monetary policy. When central banks implement quantitative easing (QE), they buy securities and increase banks’ deposits accordingly. This makes for an uncertain impact on the economy: banks must use the extra reserves to expand their loans, and those additional loans must fund increases in demand for goods and services.

But if central banks increased the quantity of CBDC held by the public, providing so called ‘helicopter money’, it would immediately impact household spending. This would be a ‘highly unconventional’ monetary policy but is not beyond the pale. Two ex-Fed economists have suggested doing just that in response to COVID.

Furthermore, by providing competition to banks, a CBDC could spur the emergence of a more efficient retail payment system. That said, an efficient payment system is possible without a CBDC. Many countries already have retail instant payment services, and the US is preparing to launch its own, FedNow, in 2023.

Where CBDC could make a considerable difference is with cross-border payments. These transactions involve much back and forth between parties. This is typically the type of transaction that could become cheaper thanks to DLT because it allows the whole network to be updated simultaneously.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, a CBDC could provide a platform for private-sector financial innovations based on DLT. There has been an explosion of DLT-based ‘coins’ with the potential to revolutionize the payments system. Central banks could support these new players, just like they support commercial banks.

As discussed above, central banks would likely issue CBDCs as tokens rather than accounts. The validity of transactions in an account-based system depends on identifying the payor. By contrast, in a token-based system, the validity of transactions depends on the authenticity of the ‘money’ being transferred. For instance, cash and cryptocurrencies are token-based systems.

Validation of CBDC transactions would be a hybrid between the permissionless crypto system, where transactions are validated by a large number of unknown validators and the centralized validation of commercial banks transactions. This is because, based on current technology, permissionless validation of CBDC transactions would be very expensive. A more efficient validation system would be for selected permitted entities to perform the validation and updating of the CBDC ledger.

Finally, the central bank would likely avoid interacting directly with CBDC holders to preserve privacy and create space for financial innovation by private operators. Instead, the central bank could issue the token to custodians or intermediaries that could issue their own tokens, 100% backed by CBDC.

In the current legal environment, with Anti Money Laundering (AML) and Know Your Customer (KYC) rules, tokens would very likely be held in accounts linked to specific individuals. However, the identity of the account holders would not be needed to validate transactions.

Market focus on DLT-driven financial innovation so far has been mainly on various cryptocurrencies. Yet DLT could also completely reconfigure payment systems and fundamentally change the role of traditional financial intermediaries such as banks.

Understandably, given the disruptive potential of CBDC, central banks want to proceed cautiously. Nevertheless, the blockchain and DLT revolution is unstoppable, and central banks have no choice but to get involved. That is why, while many issues related to CBDC are still unresolved, CBDC issuance in major advanced economies is a matter of when rather than if.

The CBDC and DLT landscape is rapidly changing. To read a summary of the latest academic research on the subject, click here.

Spring sale - Prime Membership only £3 for 3 months! Get trade ideas and macro insights now

Your subscription has been successfully canceled.

Discount Applied - Your subscription has now updated with Coupon and from next payment Discount will be applied.