Europe | Global | Monetary Policy & Inflation | UK

Europe | Global | Monetary Policy & Inflation | UK

The ongoing inflation crisis has been a hard PR battle for the Bank of England, the UK’s central bank. To some, their interest rate rises have added further pressure to beleaguered households already suffering in the cost-of-living crisis. Yet to others, they were ‘asleep at the wheel’, too slow to raise rates.

Senior BoE figures have not exactly helped themselves. Journalists and social media have leapt on their quotes to claim the institution is out of touch with ordinary people. Much of this has focused on their wish that wages do not rise too fast:

BoE Governor Andrew Bailey: ‘…we do need to see restraint in pay bargaining otherwise it will get out of control…’

BoE Chief Economist Huw Pill: ‘…someone needs to accept that they’re worse off and stop trying to maintain their real spending power by bidding up prices, whether higher wages or passing energy costs through on to customers…’

Both quotes were quickly backpedalled (or at least reworded). But they raise an important question: why are central banks so worried about wage growth? The BoE is not alone in this. ECB President Christine Lagarde recently noted that wage growth is the main upward driver of inflation (contrasting energy’s falling effect).

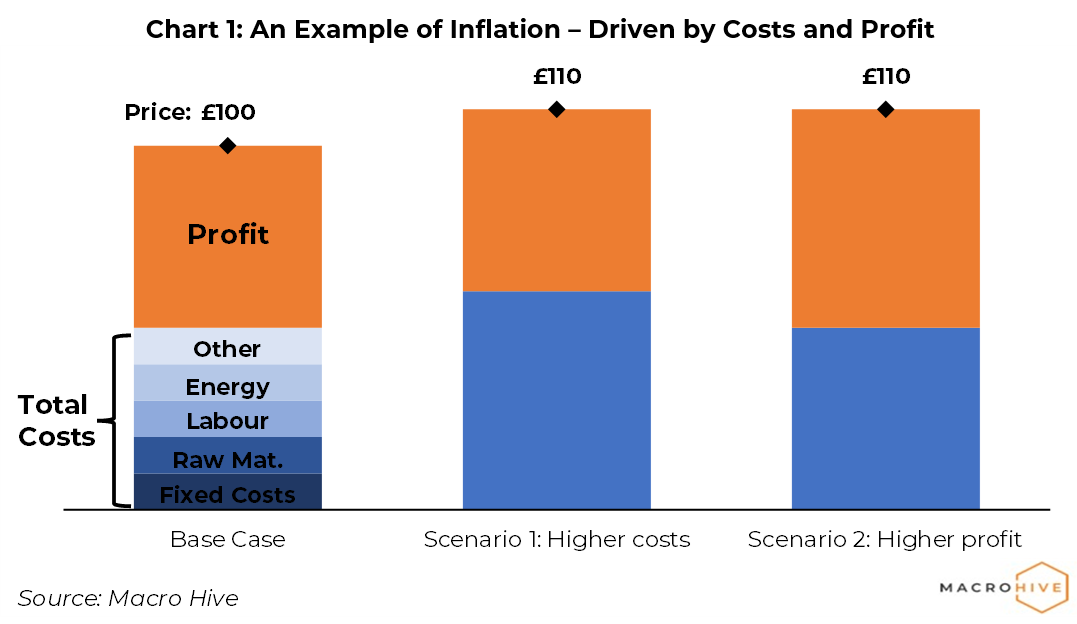

The reason is simple. Higher wages can mean higher inflation. Consider a simple example. Imagine a TV costs £100 for a consumer to buy. Two factors determine this price:

For a price rise to occur (that is: inflation), either the cost of making the TV has risen (and the company has retained the same profit), or the company has simply increased its profit (even though costs have remained unchanged). Regardless, the net result is the same: a higher price for the consumer (Chart 1).

In reality, it can be more nuanced. For example, if costs rose £10, a company might charge £105 for a TV in the belief that customers would refuse to pay the full £110. In that case, both the consumer and company have paid £5 more for the TV; they have shared the burden of inflation.

So, what determines costs, and what determines profit? This is where wages come in.

We can think of profits as a function of the supply/demand balance of the TV. When consumers have more money to spend (e.g. higher wages), their demand for TVs rises. Therefore, the company can afford to raise its prices and hence its profit.

Similarly, if a new company emerges selling identical TVs, then there is more supply chasing the same amount of demand. As a result, the company must cut its TV prices, and therefore its profits, to attract buyers.

An important conclusion is a richer consumer means greater buying power, which (all else equal) means higher prices.

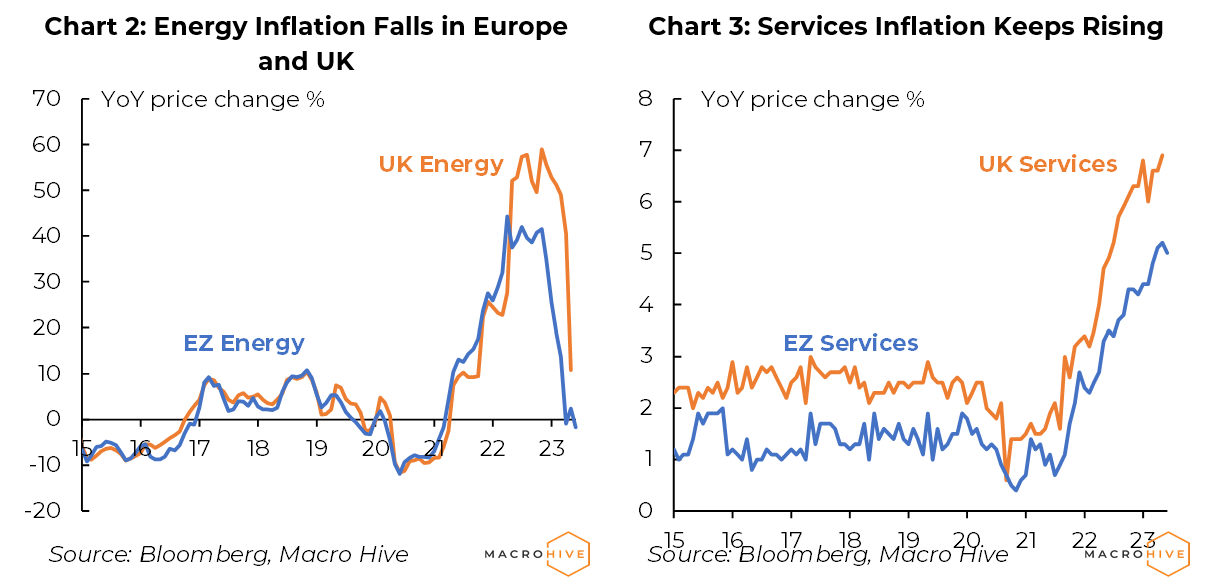

Costs, meanwhile, are driven by several factors (Chart 1). Raw materials and energy prices were the dominant drivers of cost rises in Europe immediately following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 (Chart 2). But these are now fading. Now, the price rises are being seen more in the wage-intensive services sector (Chart 3).

The reason is, if companies need to pay higher wages, they will need to raise prices if they wish to maintain their profit margin.

In short, wages affect both the demand (profit) and the cost side of the equation.

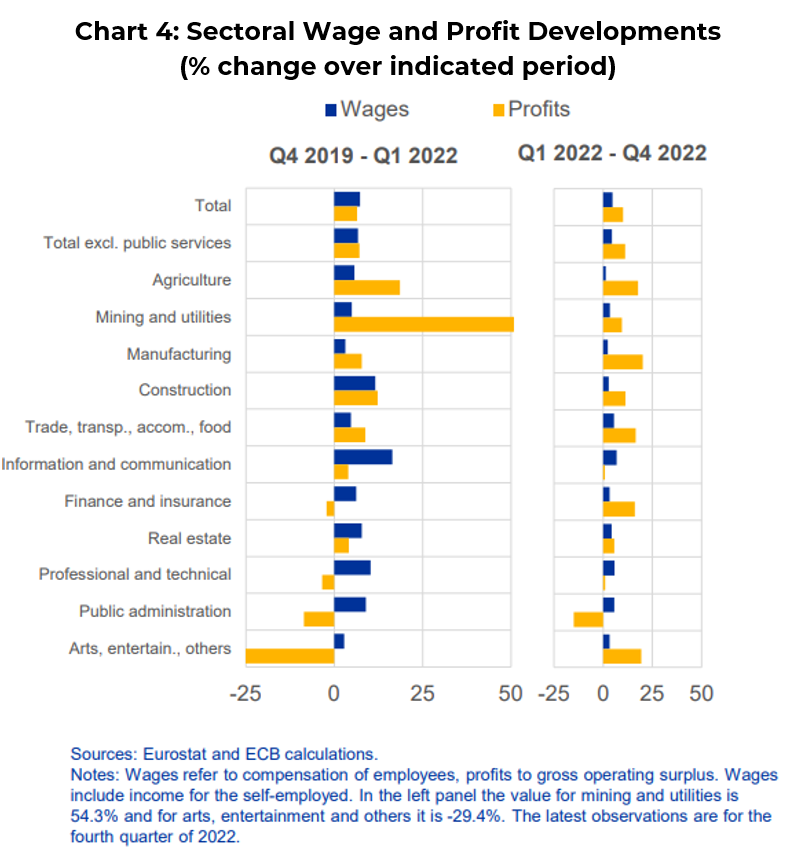

So, unsurprisingly, central banks are wary of wage prices. But the ECB has also highlighted the role of corporate profits, as Executive Board Member Isabel Schnabel noted in her most recent speech. In fact, ECB Chief Economist Philip Lane has been dedicating a page to rising profits in his presentations since March, highlighting that 2022 profits grew far faster than wages in most sectors (Chart 4, from his recent publication).

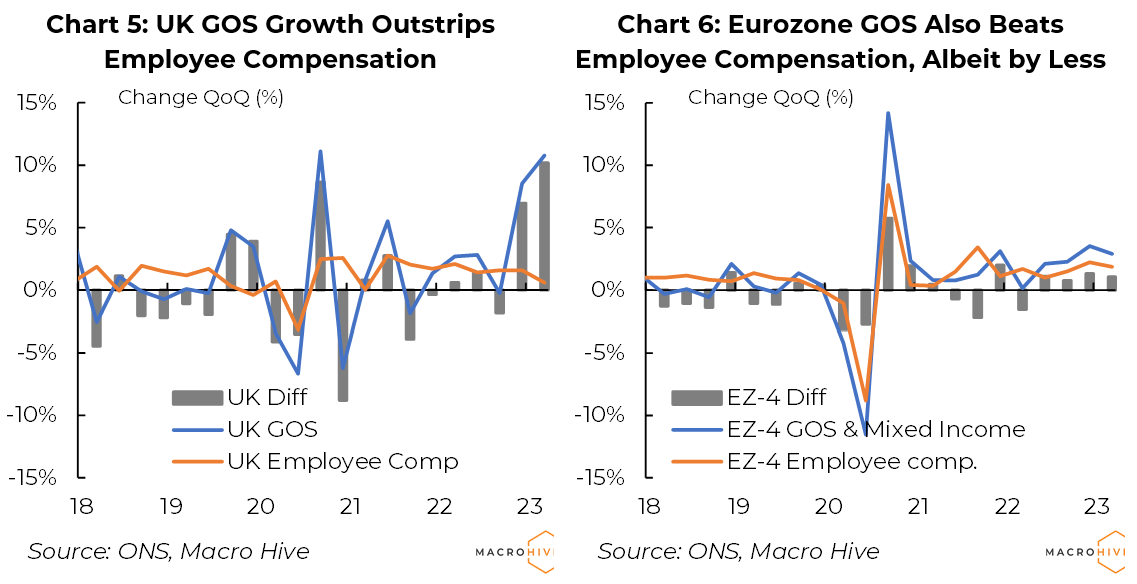

Compared with the ECB, the BoE has stuck to a very different line. Deputy Governor Ben Broadbent was emphatic at the last press conference: ‘…there’s no increase in the profit share of national income [unlike in Europe]…’.

Other members of the BoE MPC have shared a similar sentiment.

External MPC member Jonathan Haskel concluded that despite the apparent jump in ‘gross operating surplus’ (GOS, that is, corporate profits plus other things) in Q4 2022, this was more to do with subsidies and rental income, and that ‘the contribution of rising profits to recent inflation is small’. Support for this argument goes across the spectrum. Recently, dovish MPC member Swati Dhingra investigated profiteering behaviour by looking at comparisons in PPI (producer inflation) and CPI (consumer inflation) and found ‘profit margins are not rising’. New-joiner Megan Greene noted buoyed corporate pricing power, but provided little extra detail.

Yet these comments struggle to explain the jump in GOS in the UK in Q1 (far above the employee compensation share, Chart 5). EZ beats (which have come under far more scrutiny) have been far less by comparison (Chart 6).

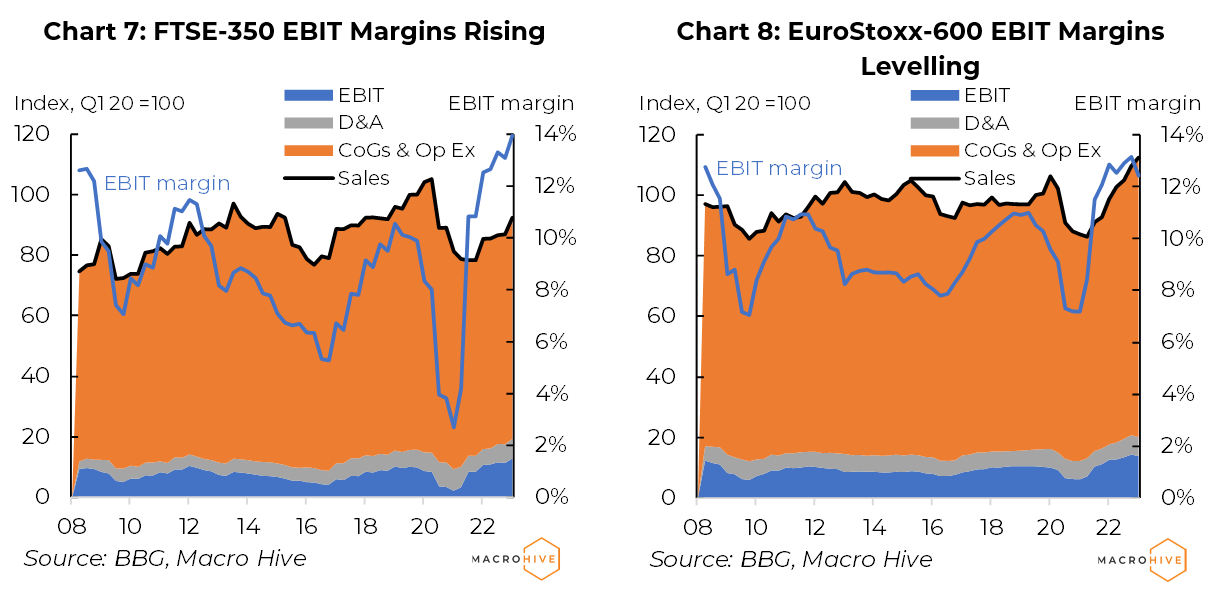

Corporate data also suggests profits are rising. For companies within the FTSE-350 (the 350 largest companies on the London Stock Exchange) earnings before interest and tax (EBIT) margins rose sharply above their previous historic average in 2022 and have continued to rise in 2023 (Chart 7). The effect is even stronger among firms in the FTSE-100.

Meanwhile, Eurozone big companies (EuroStoxx-600) saw a rise post-COVID, but the EBIT margin appears to have levelled off in Q1 2023 (Chart 8).

There are nuances to this, as Dhingra notes. UK firms also have revenues and profits from abroad. Many are not consumer-facing. There are big sector divergences (oil and gas companies have benefited the most). And EBIT numbers do not include interest payments (which have risen since the BoE started hiking) or tax (which has risen on average for corporates over the period due to the energy profit levy).

Despite the nuances, we can conclude at least that (at least as well as European ones) UK firms have defended – if not expanded – their profit margins through this crisis.

This brings us to the crux of Pill’s (admittedly heavy-handed) comments: if prices are rising, someone must pay for it. It could be corporates, individuals or governments. So what can and do governments do to help? And why are public sector pay rises perhaps not such an inflationary worry?

UK wages have soared. BoE hiking expectations have followed. The market is now pricing a peak Bank Rate of 5.75% – in other words, a 25bp hike at each of the year’s remaining five meetings.

Evidently, the market believes the BoE remains highly reactive to wages. However, and more importantly, the market believes the BoE remains highly reactive to private sector wages, which jumped to +7.9% YoY. The market shares this opinion for two reasons:

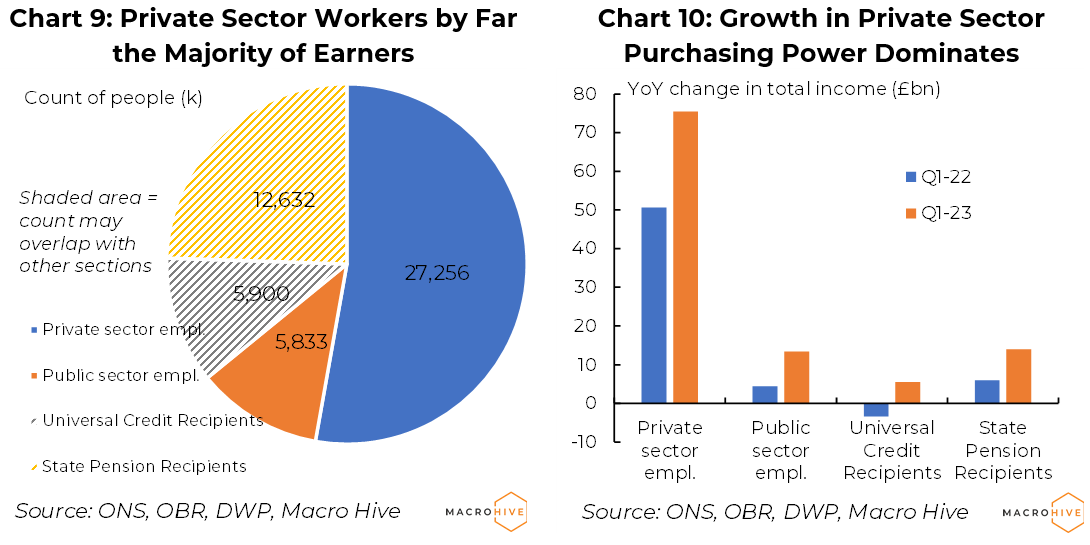

The scale difference between public and private sector pay is an important factor. In terms of total purchasing power rise (the rise in pay/receipts multiplied by the number of people receiving that pay), the public sector has only seen around the same rise in pay as state pensioners in the last 12 months (Chart 10).

Public sector wages, state pensions and other benefits raises fall into the category of the government taking on some of the cost of inflation that would have otherwise fallen on the consumer. The efficacy of such raises is unclear. Instead, the decisions tend to be political (e.g., keeping to the triple lock). While it is in the interests of all parties to press for pay rises to shield themselves against cost rises, outside the private sector, it is ultimately up to the government how such spending should be apportioned.

What would happen if the government subsidised consumer prices instead of raising incomes via government spending?

That was the logic of the UK’s energy price caps (the EPG). These shaved an estimated 1ppt from headline inflation on commencement and potentially as much as 3ppt through reducing costs across supply chains. However, the sum cost (c.£78bn over two years), even net of the £40bn energy windfall tax, was nearly equivalent to the combined raises in public-sector pay, universal credit and state pension over the last year.

Furthermore, implementing such a policy outside the energy world (where prices are determined by Ofgem, and there are relatively few suppliers) would probably be much harder. The government is investigating price caps on basic food, but whether this will be a subsidy or part of a larger shift towards policies targeting profits remains unclear.

In Europe, the ECB (and the Commission), have turned increasingly critical on uncapped government spending to offset inflationary pain. Across the spectrum, they have criticised untargeted measures. But governments need to be seen to do something, and subsidies are vote winners.

The UK government may have dragged its feet on windfall profit taxes, but the same was not true across much of Europe. Nations there were quick to impose such through 2022 (mainly on energy firms, but also banks in Spain). It could be a warning of how quickly governments could shift to more broadly target ‘excess’ profits.

With governments needing to show a path to balanced budgets but also continue supporting households, targeting profits may be an easy win. Already, populists are in charge in Italy. Spain will probably see new or strengthened populists in the government after its election next month. They may be keener to take on such a role. Meanwhile, Germany is not due an election before 2025, but the far-right are polling strongly.

In short, European equities may well face new headwinds if governments start to see them as any easy scapegoat. That may produce a ‘fairer’ sharing of the inflation burden, or it could trigger some far more systemic shifts. Either way, it is worth paying attention to.

Spring sale - Prime Membership only £3 for 3 months! Get trade ideas and macro insights now

Your subscription has been successfully canceled.

Discount Applied - Your subscription has now updated with Coupon and from next payment Discount will be applied.