Economics & Growth | Global | Monetary Policy & Inflation | US

Economics & Growth | Global | Monetary Policy & Inflation | US

This is an edited transcript of our podcast episode with Geoff Rubin, published 31 March 2023. Geoff is Senior Managing Director and Chief Investment Strategist at CPP Investments. The Canadian Pension Plan is one of the world’s leading pension managers with over $530bn in assets. Geoff is responsible for designing and implementing CPP Investments’ long-term investment strategy. He joined CPP Investments in 2011, at the inception of the former Total Portfolio Management department. Previously, Geoff held finance roles with Fannie Mae and Capital One Financial where he managed the global balance sheet. In this podcast, we discuss the pros and cons of the 60:40 portfolio, fixed income as a diversifier, passive vs active, and much more. While we have tried to make the transcript as accurate as possible, if you do notice any errors, let me know by email.

Welcome to Macro Hive Conversations with Bilal Hafeez. Macro Hive helps educate investors and provide investment insights for all markets, from crypto to equities to bonds. For our latest views, visit macrohive.com. Before I start my conversation, I have three requests. First, please make sure to subscribe to this podcast show on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcast shows. Leave some nice feedback and let your friends know about the show. My second request is that you sign up to our free weekly newsletter that contains market insights and unlocked content. You can sign up for that at macrohive.com/free. All of these make a big difference to us and make the effort of putting these podcasts together well worth the while.

Finally, and my third request is that if you are a professional or institutional investor, do get in touch with me. We have a very high-octane research and analytics offering that includes access to our world-class research team, our model portfolio and trade ideas, machine learning models, and much, much more. You can email me at bilal@macrohive.com, that’s B-I-L-A-L@macrohive.com, or you can message me on Bloomberg.

Now onto this episode’s guest, Geoff Rubin. Geoff is Senior Managing Director and Chief Investment Strategist at CPP Investments. The Canadian Pension Plan is one of the world’s leading pension managers with over $530 billion in assets. Geoff is responsible for designing and implementing CPP Investments’ long-term investment strategy. He joined CPP Investments in 2011 at the inception of the Total Portfolio Management Department. Previously, Geoff held finance roles with Fannie Mae and Capital One Financial where he managed the global balance sheet. Now on two our conversation.

So greetings and welcome Geoff. It’s great to have you on the podcast show.

Geoff Rubin (01:47):

Thanks so much for having me.

Bilal Hafeez (01:49):

Well, before we get into the meat of our conversation, I do like to ask my guests something about their origin story. What did you study at university? Was it inevitable you’d end up in finance and what are some of the highlights of your career until this point?

Geoff Rubin (02:01):

Sure. So I studied economics both undergrad and graduate, and I don’t believe it was inevitable that I would find my way to finance. The type of economics that I studied was more focused on microeconomics and labour economics, and I’m going to get my one big brag out of the way early on this one. In graduate school, I studied with David Card who was the recent recipient of the Nobel Prize in Labour Economics, which is incredibly gratifying, but was an area of study that was not really immediately or directly related to investing in finance, but helped develop a rigorous thinking and approach in the use of evidence and data in order to make well-grounded decisions that I think applies really well to investing.

So I think that my academic background prepared me for the role that I’ve stepped into, even though it was not a finance degree in particular.

Bilal Hafeez (02:52):

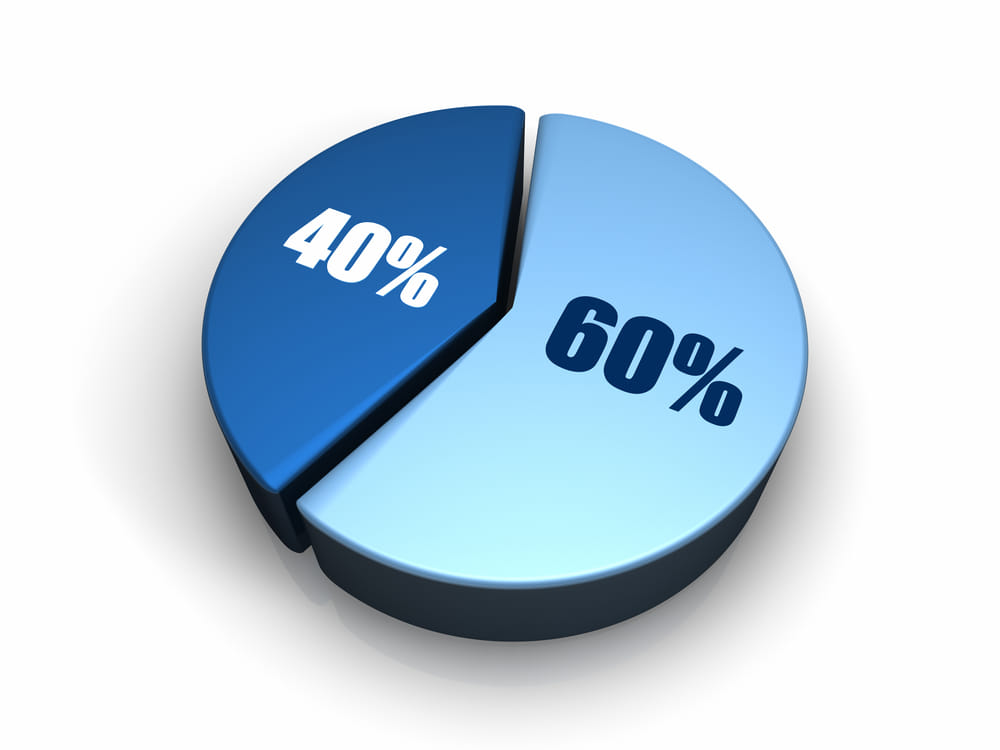

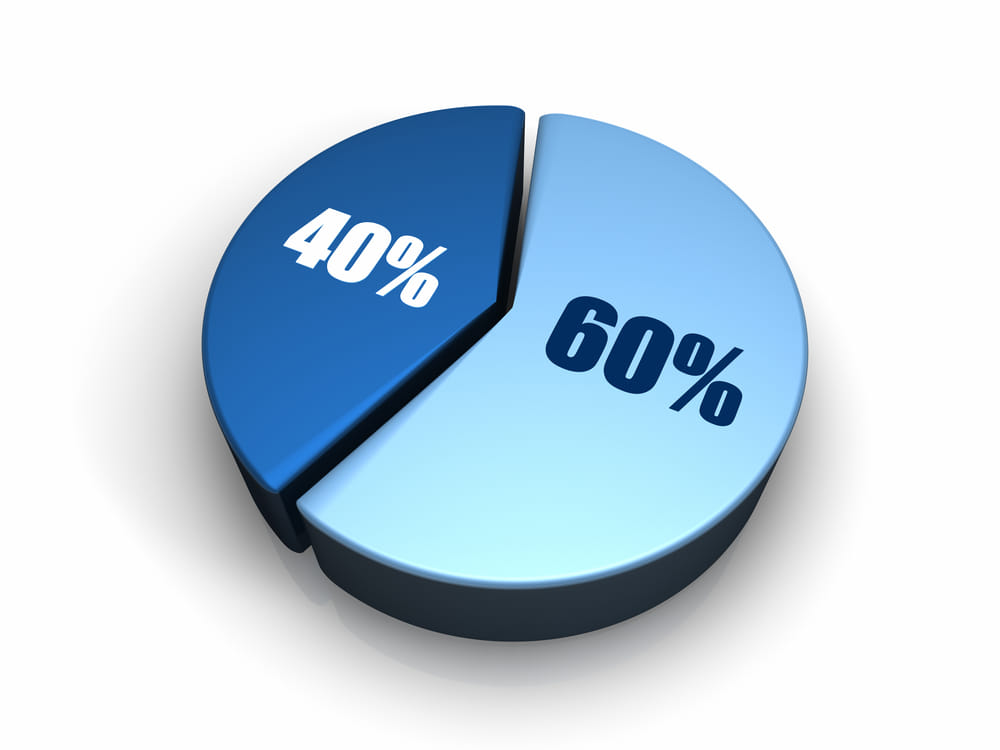

And now speaking about investment, we hear a lot about the 60/40 portfolio. It seems to be the reference point for everybody in the industry, whether you are a retail investor to an institutional investor. That seems to be the thing we always refer back to. Now, what are your thoughts on 60/40?

Geoff Rubin (03:09):

It’s not a mistake, but that’s a common yardstick or a common device for many investors, though I would say Bilal, it’s really important for every investor to start by thinking really carefully and deeply about what is the right portfolio designed for their particular problem, for their liabilities that they face, for their risk appetites, for their aims and objectives of what they’re trying to achieve with their investment portfolio. I don’t believe that 60/40 as a portfolio is going to be right for everybody, but for many investors, I think that level of risk is probably appropriate given their circumstance and the composition of that risk. A blend of equities and fixed income I think starts to introduce some really meaningful diversification into the portfolio. It’s still dominated, the performance of that portfolio is still dominated by equity performance over time. I think that’s well understood, but I also think that fixed income exposure, duration exposure is the first real and prominent diversifier to portfolios that are otherwise exposed solely to equity risk. I think it’s a great idea to start building portfolios like that.

I’ve seen some interesting work on the 60/40 portfolio that suggests it’s also pretty close to the capital market line and its tangency to many utility curves, so it doesn’t require leverage to really implement. It can be done broadly physically, so it’s relatively easy to implement as well, but I think there’s always things one needs to stay on top of with these types of portfolios and in an environment where the level and volatility of inflation dominates, some of the diversifying characteristics of fixed income and equity will be lost. In those kinds of environments, all asset classes, equity and fixed income among many others, they’re all impacted by surprises and inflation and the corresponding impacted discount rates.

So while I think it’s a really important first step in diversifying a portfolio, I don’t know that it’s complete and I don’t know that it’s necessarily going to work in all environments.

Bilal Hafeez (05:09):

And then a related point to the 60/40, 60% equities, 40% bonds is the passive active debates where it goes a step further to say, actually not only do you not need to worry about the asset allocation, you can actually passively just buy an ETF through some cheap low-cost ETF provider, get your 60/40 combination and then that’s it. You can sit back and make those nice returns over time. So what are your thoughts on the passive versus active debate?

Geoff Rubin (05:36):

A couple of thoughts there, and again, I think maybe you and I agree talking about this theme of built-to-purpose and built-to-suit for every investor. I think some investors are well positioned to invest actively and pursue not just the underlying systematic exposure, the right overall, call it beta profile of the portfolio they’re trying to pursue, but can also add additional alpha value, add on top of that if they’re very clear around their sources of edge or advantage for doing so actively.

I think other investors are really smart to understand and know where their limits lie and might appreciate that they don’t have advantages. They don’t have edge over other fierce competitors in the marketplace and really try to focus their efforts on building the right passive or beta portfolio to deliver the overall exposure that they want. Bilal, I’m increasingly of the mind that passive and active is not a binary choice. There’s a wide spectrum within the two.

I think we need to make active decisions as investors even when it comes to investing in asset classes or geographies or sectors that one might access through something like an ETF, but the choice of investing in that sector in the first place is a very active decision. Even the decision on the level of risk that we want to take in our portfolios, that might not require edge or advantage in the way that a stock selection alpha proposition works, but it’s still a really active decision in that one is departing from norms or benchmarks or market averages and thinking about what’s the right portfolio for them in their circumstance, and I like to think that’s at some level an active decision as well.

So actually, I don’t know that it’s as much of an issue of being on one side or the other of active and passive. I think it’s about finding that spot in the spectrum that corresponds to what you’re trying to accomplish as an institution where your advantages and edges lie in pursuit of real active returns.

Bilal Hafeez (07:45):

And actually, you’re probably right, you point out that actually at some point there’s discretion somewhere along the line. Even the initial decision to buy the ETF, there’s an active decision there, so it depends on what level down you are applying that discretion.

Geoff Rubin (07:58):

That’s right.

Bilal Hafeez (07:59):

Yeah. An alternative to the whole 60/40 model is the so-called endowment model popularised by Swensen and the university endowments in the US, and the argument there is actually, you can start to earn liquidity premia if you start to buy longer dated illiquid assets. What are your thoughts on the endowment model number one, and secondly, is that something you are an advocate for?

Geoff Rubin (08:22):

I think the endowments, and led by Yale initially, I think really did a terrific job of two different elements of that model. The first is the one that you describe, which is recognising that pick equity exposure and private equity, that they can gather that equity exposure not through the list of public markets but through private markets where that illiquidity premium that you described probably existed at the time. In fact, I would say certainly existed at the time. And as a result, we’re able to generate additional incremental returns for a given amount of equity exposure within their portfolio.

I think those organisations also did a terrific job of anticipating what the impact of that illiquidity would be on their ability to meet liabilities through different environments. They actually did the hard work to understand the nature of their endowments and funds, the nature of the funding rules that they were supporting at their institutions. Not every institution did that work well. There were a few high profile and notable examples that were revealed in the GFC, but I think broadly speaking, I think they did a really nice job of understanding the asset class and its contribution portfolio and understanding themselves and their ability to absorb that kind of investment strategy given their particular liquidity and capital circumstance.

As one rolls forward over time, a couple of things come to mind. One is I think that notion of the illiquidity premium, associated with private assets, I think is increasingly challenged. I think at the outset of the endowment model it was a relatively new asset class with very wide spreads and terrific risk premia to exploit and take advantage of. As those asset classes have matured, I think arguably that premia has been compressed and in the current marketplace, I even occasionally see situations where I think investors in some areas might be willing to pay up for the accounting stability of those assets in ways that goes beyond their actual economic performance, their actual underlying performance. The fact that these asset classes are illiquid has the, some would say beneficial effect of dampening the reported volatility of their values.

Then again, I don’t know if that really corresponds to the actual volatility of the economic performance of the asset, but under the normal reporting procedures is going to suggest or reveal a diminished level of risk, and when investors start paying up for that, that is going to compress the illiquidity premium. Could it even reverse the illiquidity premium? Might there be private asset classes where investors are willing to pay up for illiquidity because of that accounting artefact? Wow, that is a really tricky world and one in which I think institutions equipped to hold public listed alternatives with higher accounting volatility might actually be better positioned to generate outsized returns over time. So I do worry a little bit about that private-asset-heavy approach that many of the endowments have taken.

There’s another element of that endowment approach, which I think institutions have got to be very mindful of, is that the endowments, again, really understanding themselves as institutions chose to typically express those private asset strategies with partners as LPs in which the great majority of control was given over to the general partners with whom they work. I think many of those large GPs are changing their models now as well, from one in which it’s really important to generate extraordinary investment returns, risk adjusted returns, to one in which they’re seeking to deliver a level of returns that is sufficient to continue gathering assets. Many of the larger general partners are moving into asset gathering and AUM driven models of performance, and I think in that world, the amount of alpha and the share of that alpha that will accrue to the LPs will be under constant attack.

So I do worry a little bit that the endowment model, which was so successful for a couple of decades, as you would expect with any innovation over time, the market catches up and I think this notion of investing in private assets as an LP with very large general partners, I think the returns to that will compress over time.

Bilal Hafeez (13:07):

Yeah, I share your scepticism on private markets. I think it’s important to really look clearly at the incentive structure and the recent returns as well. Now, let me ask you then about your CPP Investments approach. We’ve talked about public markets, asset allocation and endowment models. So what’s your framework? How do you guys go about doing things?

Geoff Rubin (13:29):

We start with a very clear consideration of again, what it is we are trying to accomplish, and they’d be CPP Investments invests on behalf of the Canada Pension Plan, which is the Canadian equivalent of the US Social Security System with a really important distinction that it is a partially and in some cases fully funded plan in which today’s contributions do not just go to meet contemporaneous obligations of retirees, but there’s an excess that gets invested by CPP Investments. Within that construct, we have to think very carefully about what is the right portfolio and the right level of risk that we need to maintain in order to deliver against the objectives and the expectations that we face?

Our mandate is to maximise returns at a targeted level of risk. It is a level of risk which for the majority of our fund is the same level of risk as that of an 85% equity and 15% fixed income portfolio. So it’s a higher level of targeted risk and we expect to generate a higher, a correspondingly higher level of returns. We do not believe that a portfolio comprised of 85% equity and 15% fixed income is the right portfolio to deliver at that level of risk. So we want a very different portfolio design, one which is more diversified, one which is more active, one that’s global, one that looks across all manner of different asset classes and has a breadth, that allows us to think about relative value propositions across all of these different opportunities, but it’s going to be at that level of risk. So below that, the first step we take is a very careful consideration of what are we trying to achieve? What’s the right portfolio to deliver that?

I’d say next, we think about the total portfolio approach as a unifying means to look at all of these different asset strategies using the same apples to apples lens of risk factor exposure. This is the second step of really what we do is think about how all of these different strategies are fundamentally contributing to the composition of the overall portfolio. We don’t have a policy portfolio. We don’t have specific allocations to different types of asset classes or different sleeves. We want to think about the portfolio in its entirety and make sure that we are always optimising that portfolio, maintaining a targeted level risk and pursuing the greatest amount of return we can return, that is driven both by systematic risks and the idiosyncratic stock selection, security selection risks that we might take where we have edge and advantage.

So we are very active in our pursuits of an investment portfolio, but only where we believe our advantages of size and horizon and certainty of assets and the quality of partnerships we have, and I would say the cogency with which we think about our investment problem.

Bilal Hafeez (16:36):

So you did mention risk factor there, and I just wanted to clarify. When you say target risk, do you mean volatility or are you looking at other ways of looking at risk?

Geoff Rubin (16:47):

We look at a variety of dimensions of risk. I think volatility is a useful measure and metric that allows you to broadly position the portfolio at the level of volatility, level of risk that you would expect, but that doesn’t cover the entirety of what risk really represents, which is a downside outturn that can really challenge the organisation to meet its goals and needs. I think that’s not just permanent impairment risk. That’s not just VAR or CVAR or some of the other techniques one uses. I think there’s a deeper consideration around what it is that the organization’s positioned to actually withstand as it arises. Bilal, we think quite a bit around our investment horizon here and believe that our long horizon positions us to invest with advantage and edge in certain marketplaces.

I’m reasonably convinced that horizon, it’s about the length of time one can stay in an investment that is broadly performing as expected without getting stopped out. Every investment strategy, whether it’s for the entire fund or an individual smaller strategy, is going to face downside outturns, call it VAL, call it VAR, call it whatever you want to call it. The real risk is that that emerging evidence on the performance of the strategy leads to a loss of will or conviction, even if the strategy was actually performing, broadly speaking within the envelope of expectation you would have at the outset.

For me, that represents a short horizon and represents what I think can be a really difficult failure of institutions like ours, which is to bail out on investments at the bottom. That loss of will or commitment, I think is a real threat to the longer term performance of our institutions. So you ask a great question around how should we think about risk? For me, fundamentally, we should think about risk as the kind of outturns or events that would lead to a loss of will or commitment and ensure that your investment strategies reside within, inside those boundaries because if you actually run a strategy which trips up against those behavioural boundaries, those appetite boundaries, you face that risk of being stopped out in which I think that’s how institutions like ours can really do disservice to the contributors and beneficiaries for whom we’re trying to act.

Bilal Hafeez (19:23):

That’s a very hard thing to institute. It’s almost a cultural phenomenon of an organisation. I’ve seen so many organisations that on paper claim that they’re going to stay in the strategy even if it has a drawdown, but then when they experience the drawdown, they’re out. So you talked about behaviour and attitude, and so that suggests that there’s something deeper going on. It’s about the culture of an organisation and how do you create a culture that doesn’t bail out of a strategy where you said that you’ll stay in it even within a certain drawdown?

Geoff Rubin (19:57):

Bilal, I love that question and I think this is a fascinating dynamic. I think it starts with governance and I think we have a terrific opportunity here at CPPIB with our arms length positioning from the governmental stewards that oversee the Canada Pension Plan. We have a professional board that really understands what our mission is and has the mindset perspective, length of term that I think really lends itself to this kind of behavioural strength in terms of remaining committed, but I don’t know if that’s enough.

For me, the quality of the investment process and the care and clarity with which you lay out expectations before launching a strategy, I think that is really, really important. Shame on you if you don’t lay out very clearly what it’s not just going to look like, what it’s going to feel like to experience the volatility and the drawdowns and the inevitable fluctuations and performance and how that’s going to feel in terms of not just impact to the fund and its ability to meet its obligations, but what it’s going to feel like in terms of personal performance, what it’s going to feel like in terms of the individual teams that are running the strategies and their incentive compensation, what it’s going to feel like in terms of external profile of what it’s going to get, what it’s going to feel like when one compares that institution to its closest peers.

These might all be things that are of secondary importance when the strategy is performing well, but rise to the fore when there’s difficult experiences, when there’s difficult realisations of performance. I think it’s really, really important to do that work in advance of the downturn, to do that work in advance of the problem so that you are not trying to parse through what is signal and what is noise at the time of the problem, but are instead really thinking very clearly in advance of what it can look like, what it can feel like, so you build that kind of resilience.

Bilal, despite all of that work, there are institutions that face quarterly redemptions from customers. There’re institutions that by their nature are going to have shorter horizons. The sin is not having that circumstance. The sin is not building an investment strategy suited to that circumstance. We have an opportunity to be longer horizon here. I think it’s our job to make sure we’re taking full advantage of that, both with our investment strategy and with that behavioural element you described to make sure everyone is really in the picture as to how these strategies are likely to perform so we can stay committed to them in times good and bad.

Bilal Hafeez (22:52):

That’s a great point in terms of being transparent about all the distribution of the returns. You did mention something on governance, which I thought was interesting that you said there’s a professional board because certainly in other countries, the UK included, the governance of pension funds, you tend to have non-finance specialists who are on the board of trustees, so it’s an odd setup where the people overseeing the executive are not financially experienced in the same way. What are your thoughts on that as a governance model? It’s very common around the world. Here we are.

Geoff Rubin (23:26):

I’m not terribly judgmental on these things, Bilal, in terms of it being good or bad. It just is, and I think if that is your board, that’s part of the investment challenge. That’s not adjacent to, that’s not in addition to. That is fundamental to the effective design of an investment strategy and investment portfolio. If you have a board with greater or lesser experience with and commitment to and focus on certain elements of an investment strategy, think about the use of leverage in derivatives, for example. I think there are certain boards where I think with sufficient explanation and groundwork and doing all of the effort in advance to talk about what this means, I think that can be a hugely valuable part of their investment strategy.

There are other governance constructs where that is just not going to work, and you can talk about changing the governance constructs. You can talk about trying to do the work with those kinds of boards in order to over time build confidence and resilience. I think those are all great things. In the meantime, don’t design a portfolio that will run afoul of the capabilities of the governance construct that is in place. Different horses for different courses on this one, Bilal. I’m not convinced that it’s better or worse. I think it’s just our jobs as investors to be very thoughtful about what those conditions are when we set about to build our organisations, our strategies, our portfolios.

Bilal Hafeez (24:57):

No, that’s a great point. Now moving on to… We touched at the beginning of our conversation about inflation. You touched on that and how assets perform and obviously we are in this inflationary environment. Last year, bonds didn’t perform well. Obviously inflation was high, didn’t act as a diversified. So how have you structured your portfolios to weather these inflation storms?

Geoff Rubin (25:18):

I think it’s very difficult for institutional investors of our size and nature to entirely insulate ourselves from high and volatile inflation environments. It’s just very difficult. I think those kinds of environments where inflation is unpredictable, it is volatile, I think raises discount rates and diminishes values across the entire asset spectrum. Of course, there’s opportunity to invest in insurance linked bonds or to invest in commodities of types, or even infrastructure assets that have particular types of underlying revenue structures in which there’s latitude to change the revenue stream and in a way that’s tuned to realise inflation.

There are techniques that we can round some of the sharp corners of the portfolio to deliver some better performance in high volatile inflation environments, but broadly speaking, those are difficult and challenging investment markets. The loss of diversification is a real problem for institutions that have relied upon the negative correlation between equities and fixed income in a low and stable inflation environment since the 1980s. So it’s difficult. We are spending quite a bit of time to position ourselves to minimise some of the impact of these outturns.

I think frankly, an unanchored inflation is going to be difficult for economies and it’s going to be difficult for institutional investors of our type to deliver the kind of returns that we’ve experienced over the last decade or so.

Bilal Hafeez (26:54):

And I noticed earlier you talked about diversification across different dimensions, so there’s asset class, geographies as well. So on geographies, how do you think about that? Is it just a case of being as broad as possible around the world, including emerging markets, how do you think about geographies?

Geoff Rubin (27:10):

We do think geography is a meaningful diversifier and the emerging market and developed market distinction is an important one. It’s not the only one that we take a look at when we think about our profile. We have investment offices close to 10 different offices around the world from which we invest, and we do so to benefit from that geographic diversification. We do so because that gives us opportunity to pursue investment strategies locally that would be very difficult to do just from Toronto or just from one particular spot, one particular headquarters. I think the ability to manage risk with offices around the world has been an important part of our local presence and local office strategy.

So for an institution like us, for one that has $500 billion of assets going to a trillion, we need to be broadly exposed to the drivers of growth globally. We need to be exposed to diversification. We need to be exposed to investment markets where we think there’s still opportunity to generate alpha and outsized returns. All of those factors drive us to build a broadly global portfolio that takes advantage of those opportunities.

Bilal Hafeez (28:25):

And the last question I wanted to ask about your investment process was around new assets. So we’ve had recently, obviously crypto, then there’s other new shiny toys that appear. People talk about alternative assets or investing in hedge funds or all those sorts of things. What are your thoughts on alternatives in the broader sense?

Geoff Rubin (28:45):

Our process allows us to look through asset class labels and work to understand the underlying fundamentals of virtually any asset class. So at some level, there’s no restriction by label or by type on what we can do with very, very few exceptions. That said, when we do the work on what is the true underlying proposition, what is the cash flow profile and risk profile of these assets? Hard to get terribly excited about a lot of these new ones, hard to really even understand what some of the value proposition on these more exotic assets is. Not something that we would be in any rush to add to our portfolio.

We need to think about materiality within our portfolio as well and what really moves the needle? What kinds of new investment types would justify the allocation of scarce resources like risk and capital and managerial attention and time in order to foster and cultivate, to get to a spot where it materially contributes to the performance of our portfolio. That’s something that we need to contend with as well.

So I think we do a good job of staying on top of innovation in these marketplaces. I think we are open-minded to how these investment markets evolve and how assets evolve and they sure do evolve over time. So I don’t think we have a static investment strategy by any means, but we are very careful in thinking about how these emergent assets really perform and really contribute to the overall portfolio design we want. And that I think has been an appropriately high bar for the entrance of some of this into our portfolio.

Bilal Hafeez (30:29):

Okay. Understood, and I understand the subtext there as well. Now, I did want to ask a few personal questions as well. One is, over your career, what’s the best investment advice you’ve ever received from anybody?

Geoff Rubin (30:41):

This might be advice that is a composite from many folks, but I think this… A lot of what we’ve been talking about in terms of focus on the quality of the process as opposed to the short-term results from that process. I think our jobs are to very carefully put ourselves in a position where we maximise the likelihood of success, but recognise that particularly over short horizons, there’s a lot of noise in the results that come out and not to overly index on that. Make sure that you are constantly working to improve and enhance the way in which you invest. I think that’s collectively, I think an impression that’s really been made on me. I’m not sure, are you familiar, Bilal, with the poker community and Annie Duke has a-

Bilal Hafeez (31:31):

Oh, yeah, yeah.

Geoff Rubin (31:32):

She put out where that group does a really good job of focusing on putting themselves in the best position to win a hand and often aren’t terribly fussed about the outcome of any one individual hand or pot because they realise that if they had a 70% chance of winning a particular hand and the cards fell the wrong way, that doesn’t really reflect on their process. That was just a tough draw that over time, over longer periods, if your process puts you in that kind of position to succeed, you will start to see the results that you were looking for. I think that’s a really important lesson to focus on how we are best positioning ourselves to win for the long-term and not getting too excited or too discouraged by the shorter-term outturns.

Bilal Hafeez (32:24):

Yep. No, no, I totally agree with that. Now, another question. This is more advice for youngsters. So what advice would you give to people leaving university to enter the jobs market?

Geoff Rubin (32:35):

Good luck. I would say quite a bit of a mess there they’re walking into, but look, Bilal, I actually am really impressed by the folks that I see coming out of university. I hear all about the Gen Z and the slacker and the… I don’t see any of that stuff with the folks I’m interacting with. I learn more from them than they learn from me, to be honest. And they’re bright, they’re ambitious. They think very finely about themselves, their careers, how they want to proceed. I think they’re a great bunch. I hope they can continue to demonstrate broad curiosity and ask lots of questions and not be afraid of not knowing the answers and walking into a room of counterparts or colleagues who are doing something different and say, ‘Wow, this is really neat stuff. I don’t have a clue of what you all are doing, but I’d love to learn. Can you teach me some of this?’

I worry a little bit about this specialisation that we’re laying on some of the junior folks and they think they need to deepen and tighten their expertise as opposed to being able to be a bit broader. I guess I would encourage anybody at that age, enjoy the breadth and curiosity of learning about a whole bunch of different stuff even as you deepen your expertise in your chosen area, make sure you maintain that broad aperture to really fill yourself out.

Bilal Hafeez (33:58):

No, no, that sounds very good. And then are there any books that really influenced you over your career?

Geoff Rubin (34:04):

I’ve enjoyed the masters old and new in that, Malkiel and Grinold and Khan, and Brian Hart and Rogoff, and then some of the newer ones. I think my favourite authors in the newer group would be Andrew Ang and Antii Ilmanen. So I really enjoy reading those. I guess I take as much inspiration from reading books outside our field. Richard Ford is probably my favourite fiction writer, and it’s just awesome to see the craft and the skill and the work and the very clear product of the effort of his process that goes into creating an extraordinary output, and I think that kind of diligence. He just published his last novel, I think he’s close to 80 now, and-

Bilal Hafeez (34:50):

Wow.

Geoff Rubin (34:50):

Just published some amazing stuff. I think that’s a real inspiration for what it means to hone one’s craft and really put your shoulder into it and do the work in order to deliver product over the long horizon. Rem Koolhaas is one of my favourite architects and has written in ways that he combines a real breadth perspective and discovery into his writing that might think at first glance as only tangentially related to architecture, but then you read it two or three times, you start to understand how he’s seeing a really big picture and distilling that into the specifics of what he does.

Bilal Hafeez (35:29):

That’s great. That was excellent. And so what’s the best way for people to follow you?

Geoff Rubin (35:34):

I’d recommend people check out the CPP Investments Insight Institute, is a really good spot where we are putting up some of our latest research, where some of the product of the folks that we convene across the industry on particular topics can come and take a look at those results. I think that’s a great spot. Our LinkedIn for CPPIB is where we post a lot of material as well. So anybody who’s interested in what we’re doing here at the organisation can really find the product of our work and how we’re thinking about investing for our particular problem in those areas.

Bilal Hafeez (36:10):

No, that’s great. And I’ll include links to everything you’ve just described there as well. So with that, thanks a lot. It was an excellent and wide-ranging conversation and good luck for this year.

Geoff Rubin (36:20):

It was great to spend time with you, Bilal, thanks.

Bilal Hafeez (36:24):

Thanks for listening to the episode. Please subscribe to the podcast show on Apple, Spotify or wherever you listen to podcasts. Leave a five-star rating, a nice comment, let other people know about the show. We’ll be very, very grateful. Finally, sign up for our free newsletter at macrohive.com/free. We’ll be back soon. So tune in then.

Spring sale - Prime Membership only £3 for 3 months! Get trade ideas and macro insights now

Your subscription has been successfully canceled.

Discount Applied - Your subscription has now updated with Coupon and from next payment Discount will be applied.