Economics & Growth | Other | US

Economics & Growth | Other | US

We hear and read often these days about the looming demographic challenges of an ageing population. This is manifesting through the extremely tight labour market due in no small part to people in their 60s retiring and dropping out of the labour force. Over the coming decade, the social security system is projected to hit a wall where it will have to curtail benefits unless it is somehow replenished.

Apart from raising taxes, it is widely assumed Congress will have to raise the age at which people can receive full benefits from 67 to 70. Regardless of whether people want to work through their 60s, many people in their later 60s simply cannot work due to declining health even if they can expect to live for another 10-20 years.

Here, we discuss a silent but growing issue: the swelling ranks of disabled people older than 60. Among prime working age people, about 5-8% have a disability that may affect their ability to work. As people enter the 55-65 range, that rises to about 20-25%, then to over a third beyond 65, and much higher after 75.

Disability includes various conditions: cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, diabetes, cancer and more. It is silent in that many people in their 60s with these conditions do not appear disabled, and we rarely see statistics about this issue in the media. But they suffer from severe health limitations, nonetheless.

This has implications for the labour force in coming years, and for America’s retirement and pension systems.

We do not have the answer, but addressing the problem is not as simple as raising the retirement age. At some point, Congress is sure to try that. It may succeed if it only affects people younger than, say, 50, where retirement still lies far in the future. This would kick the can down the road a bit – but there is still the issue of rising disability today.

We first consider current demographic trends in the labour market. These include inflation – a tight job market is keeping pressure on wages. We then explain how disability is contributing to the precipitous drop in labour force participation as people move through their 60s. Finally, we discuss the economic and policy implications of rising disability.

For all its tough talk, the Fed has been remarkably dovish in its stance toward inflation. The Fed had to push its policy rate well above 2% above the inflation rate to curb it. If the Fed were following a Taylor Rule today, the Fed Funds rate would be above 7% rather the current 5.25-5.50%.

The Fed is clearly hoping it can tame inflation without creating a hard landing or recession. Given much of the recent inflation is due to various imbalances stemming from the Covid pandemic, its strategy is apparently to wait and see if inflation declines organically as the economy returns to normal.

It remains to be seen how that works out.

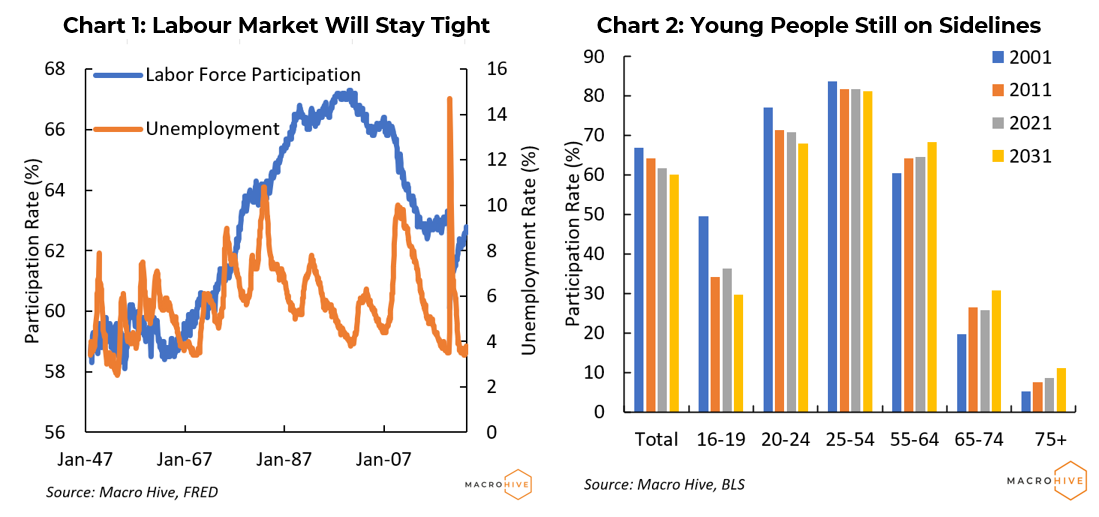

The Fed is unlikely to get much help from the labour market. Labour force participation has been very gradually recovering after collapsing in 2020. It now stands at 62.8%, versus 63.3% in early 2020 (Chart 1). It would take an additional 1.3 million workers to boost participation back to that level.

More young workers? That could well be within reach. After the financial crisis, youth employment collapsed, and people returned to, or stayed in, school (Chart 2). That has not changed much. With student loan forbearance programs ending, we can reasonably expect some of them will need to re-enter the job market. Even a modest increase in participation, to 40% (from 37% currently) for 16–19-year-olds and 72.5% for 20–24-year-olds (from 71%) would make up most of the gap. A modest increase in workers in the 55-64 bracket would more than make up the difference.

That is the good news.

The bad news is that this kind of increase will not create the kind of labour market slack that the Fed needs to help lower inflation.

Older Population Growing – The big source of labour market dropouts will be in the 65+ cohort. The overall population is expected to grow about 7% over the next decade – but the 65+ cohort will grow over 30%.

Participation for the 65-74 group collapses to around 25%. And the 55-64 cohort also drops, from over 80% to the low 60s.

Why do older workers drop out so precipitously?

We all know anecdotally that older people have more health problems. But we rarely see statistics illustrating that reality. In the section below, we illustrate how health issues rise sharply as people enter their 60s. We focus on disability and chronic conditions as a general summary of health problems that may affect one’s ability to work. Some of the major sources of disability are:

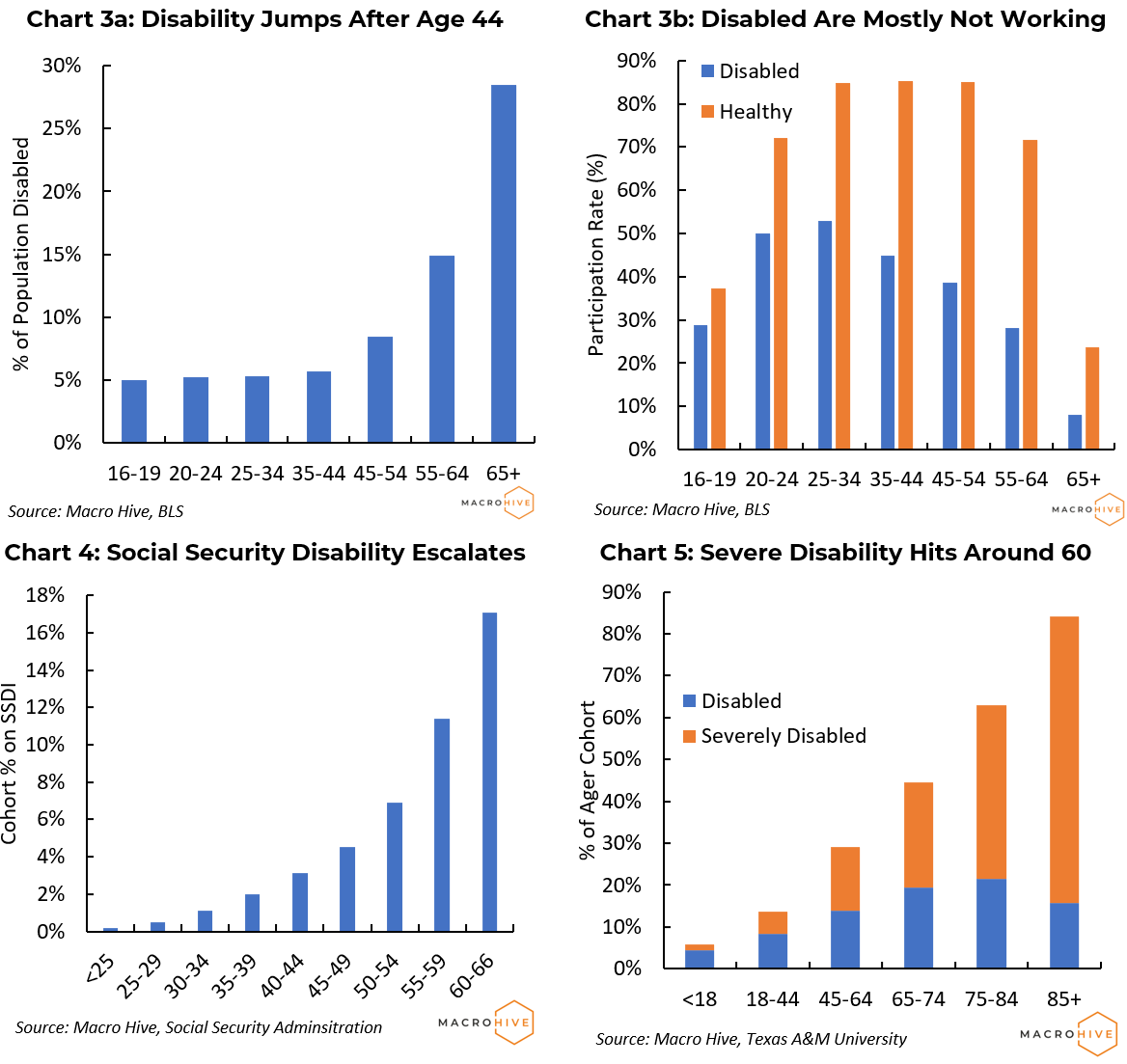

The Bureau of Labour Statistics collects self-reported data on disability as part of its monthly household survey. For ages 16-44, only about 5% of survey respondents identify as disabled (Chart 3a). (The BLS includes pregnancy as a temporary disability, which may cause a higher disability rate for this age cohort.) The number of disabled in each age cohort then rises rapidly for ages over 45. Some 15% of people in the 55-64 age group are disabled, and it jumps to 28% for those over 65.

More telling is the sharply lower labour participation rate for disabled people. For people 25 and older, the disabled participation rate is roughly half, or less, than that of healthy people (Chart 3b). This is admittedly a rough estimate of disability in the population. Given the nature of the survey, if people can work, they are less likely to report themselves as disabled even if they have health conditions considered disabilities in other types of survey. But the key point here is the clear relationship between disability and age, and how it affects peoples’ ability to work.

Generally, people cannot start collecting social security until they reach the minimum age of 62 or receive full benefits until they are 66 or 67, depending on birth year.[1] However, there is a special program for people who can receive benefits at any age up to 66 if they are under 18 or unable to work due to some disability.

The requirements to qualify for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) are more rigorous than many other disability programs or surveys. To qualify, people must have previously worked, paid into the Social Security system, and have some disability that prevents them from doing their job or adjusting to other work for at least a year (or that will lead to death within a year). They must submit proof of disability on an ongoing basis to remain eligible.

Even with these requirements, the number of people receiving SSDI benefits rises steadily with age (Chart 4). Fewer than 3% of people under 45 receive Social Security disability. That rises to 11.4% for people in the 55-59 cohort and 17.1% for peopled aged 60-65.

These numbers may seem modest, but again, the qualification requirements are rigorous. Social Security reports that nearly two thirds of applicants are denied coverage. The key point for our purposes is that disability rises steadily with age.

A survey available through the Texas A&M University (TAMU) corroborates the results above. It classifies people as disabled or severely disabled (Chart 5). Again, the number of people in each age cohort who are disabled rises with age, and the increase is mostly for the severely disabled group. In the 45-64 cohort, 30% have some degree of disability, of which half are severely disabled. For the 65-74 cohort, 45% are disabled, but the share of severely disabled rises to nearly two thirds.

The age classification scheme for this survey is different from above. However, roughly speaking, the shares of severely disabled people are of similar magnitude to what BLS and Social Security report. In the TAMU survey, about 15% of the 45-64 cohort is severely disabled. The BLS data shows about 12% of people in this age group are disabled. Given that people who can work are less likely to report they are disabled, we assume most of these people qualify as severely disabled. And about 10% of people in the 45-66 age group are receiving SSDI.

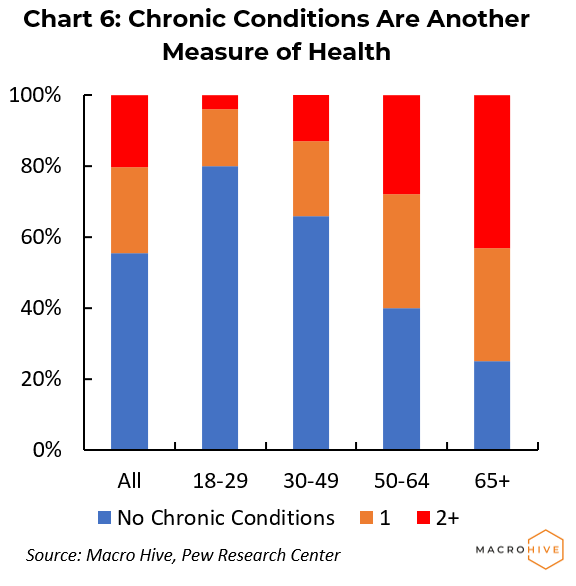

Another measure of health is people with chronic conditions (Chart 6). These include the conditions we listed above (cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, hypertension, etc.).

About 80% of young people (18-29) and two thirds of prime age people (30-50) report no chronic conditions. The share of people with no chronic conditions then falls steadily, and those with two or more chronic conditions rises sharply, to 28% for 50-64-year-olds and 43% for those 65 and older.

One question is whether a larger share of people today are becoming disabled due to poor lifestyle choices or the obesity epidemic. We have not seen much data on disability trends. Our sense is that the statistics presented above likely have been fairly constant over time.

It is a truism that social security was not intended to be the primary pension system for people as they aged. Indeed, when the system was created, the expectation was that people would work until about age 65, then die within a few years. As recently as 1950, the life expectancy for Americans was 68.5. Many people paid into the system but died before retiring, and many others died within a few years after retiring.

Today, far more people live long enough to retire, and life expectancy has extended to about 79. It is projected to rise to over 88 by the end of the century.

People today are not necessarily healthier than people back in the 1950s. Rather, today we have meds and technology to treat people for conditions they get in their 50s and 60s that killed people in earlier generations.

At some level, there is nothing surprising about these findings. We all know that people develop health problems as they get older.

But there is also an unspoken assumption that those creeping health problems do not really hit until people are well into retirement. As we noted above, many people in their 60s still look reasonably healthy even if they have disabilities that limit what they can do.

Alternatively, look no further than the ongoing debate about how to ensure that Social Security and Medicare remain viable in coming decades.

Social Security on the Block – Based on recent projections, it will be necessary to cut benefits from around 2035 unless something is done to bolster the underlying trust funds. Apart from increasing taxes, the predominant proposal is to raise the age to receive full benefits to 70. This is often justified on the basis that people are living longer. Put another way, there is an underlying assumption that a longer life span means people in their 60s can keep working as if they were still in the prime 25-54 labour force group.

The statistics above on disability across age groups makes it clear that is not the case. Each data source employs different methodologies and classifications, so it is difficult to make apples-to-apples comparisons. But roughly speaking, we estimate that at least a quarter of people become unable to work at their former jobs and need to transition to easier work or fewer hours sometime during their seventh decade. (That assumes they can find such work). Another 15% or more develop more serious health conditions that preclude working altogether.

So far, there has been little move to shore up the Social Security/Medicare trust funds, largely because of challenging politics. No one wants to raise taxes even for programs that clearly benefit everyone. Nor does anyone want to incur the wrath of older voters nearing retirement by raising the retirement age, especially as they are more likely to vote. In recent presidential elections the turnout for people over 60 have has been about 71%, versus 62% for prime-age adults and 43% for people in their 20s.

We expect younger voters will support raising the retirement age if it means avoiding a tax increase. Older people who are already receiving benefits could go either way. If raising the retirement age means their benefits will be safer, they might well support it. If they still face benefits cuts (albeit smaller ones), they would likely refuse to support it.

Too Little too Late? Still, Congress is likely to try to raise the retirement age at some point. Given the solid voting block of older voters, it may only be able to accomplish that by making it effective only for people younger than, say, 50, for whom retirement is still a long way in the future.

That may kick the proverbial can down the road a bit. In any case, the longer Congress waits, the more difficult choices become.

Still, raising the retirement age will not enable those now younger people to keep working as they enter their 60s and more of them become burdened with disabilities. In short, today’s quick fix could prove very costly in another decade or so if it proves necessary to modify the program again to accommodate people who cannot work, or if the volume of people eligible for SSDI mushrooms.

Today’s Problem Is Still There – It will certainly not make the current disability problem go away. In coming years, society will have to somehow address these kinds of issues:

As mentioned, we do not have answers to these problems. Our purpose here has been to draw attention to an issue that has long been with us – but is about to grow sharply in coming years.

It is an open question whether society and policymakers take steps to address and alleviate this problem or essentially treats it with benign neglect.

Either way, we expect the labour force to shrink, perhaps faster than most people realize, with knock-on impacts on GDP growth and tax revenue. We further expect corporate America comes under increasing pressure to retain or hire older workers, with concomitant accommodations for age and disabilities. That will raise costs and hit profitability, and ultimately equity prices. We acknowledge that rising disability is hardly the biggest problem facing society. Further, these issues will rise gradually, perhaps almost imperceptibly, rather than suddenly turn into some crisis that needs an immediate solution. So it is likely to become more of yet another headwind for the economy, on top of climate change, rising debt, student loans, and other things.

Why is labour force participation projected to fall to 60% over the next decade?

The US population is expected to grow about 7%, but the cohort of people over 65 will grow some 30%. In raw numbers, overall population will expand by 22 million people, and the 65+ group will grow by 17.3 million. The working age population will grow by only 1% (or 3.7 million people). The large growth in the elderly population is due to people aging and living longer.

Why do Social Security disability statistics stop at age 66?

People move from the disability program to regular social security.

Why can’t the retirement age be raised to 70?

There is the practical consideration that many people will not be able to work to that age due to disabilities.

And then there is the politics of raising the retirement age. Younger people may support it if it means avoiding higher taxes to support the Social Security and Medicare trust funds. Older people, especially those approaching retirement, will surely oppose any move to raise the retirement age.

Congress does not want to address these political nettles until it must. Unfortunately, that will make the inevitable choices more painful when the time comes.

What are common forms of disability as people age?

Cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, diabetes, arthritis, among other things. People who have suffered strokes may suffer from physical or mental incapacities.

Why does disability rise with age?

Much of it is probably genetic. They may be prone to develop to develop heart disease or high cholesterol or arthritis no matter how healthy their lifestyle is.

Some people do hard physical labour for much of the lives and suffer from injuries or body parts that have worn out. Poor lifestyle choices are another factor. These include not exercising, eating an unhealthy diet, smoking, drinking too much alcohol, or taking drugs.

[1] People born before 1955 quality for full social security benefits when they turn 66. People born 1960 or later qualify for full benefits at 67. The qualifying age for people born between 1955 and 1960 gradually rises from 66 to 67.

[2] Rising disability with age helps explain ageism in hiring practices. Companies cannot expect people to remain with them for their full careers, but they can expect them to show up for work week in and week out with minimal disruptions. Given the choice of hiring a younger person who has a 5% chance of health issues that could be a problem or an equally or better qualified older person who might have a 30% chance of needing accommodations or being out frequently due to disabilities or doctors’ appointments, the choice is quite simple.

Spring sale - Prime Membership only £3 for 3 months! Get trade ideas and macro insights now

Your subscription has been successfully canceled.

Discount Applied - Your subscription has now updated with Coupon and from next payment Discount will be applied.