‘COP26 is a failure’, says climate activist Greta Thunberg, referring to the ongoing UN climate conference in Glasgow. ‘Net zero by 2050. Blah, blah, blah. Net zero. Blah, blah, blah. Climate neutral. Blah, blah, blah… Words that sound great but so far have led to no action.’

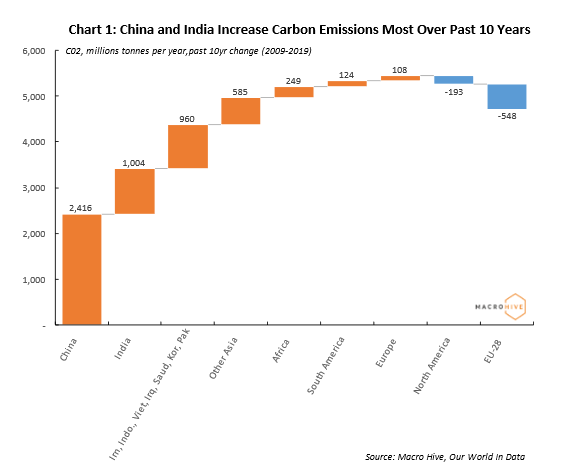

Her cynicism has some basis. CO2 emissions have increased by almost five billion tonnes per year over the past 10 years. And this is despite numerous commitments from the 1997 Kyoto Protocol onwards.

There is some good news – both developed Europe and North America have reduced annual emissions over the past decade (Chart 1). But massive increases in emissions in developing economies swamp these reductions. The two biggest culprits are China and India, together accounting for almost 70% of the increase. Both countries have set notably less aggressive targets on net zero emissions at COP26.

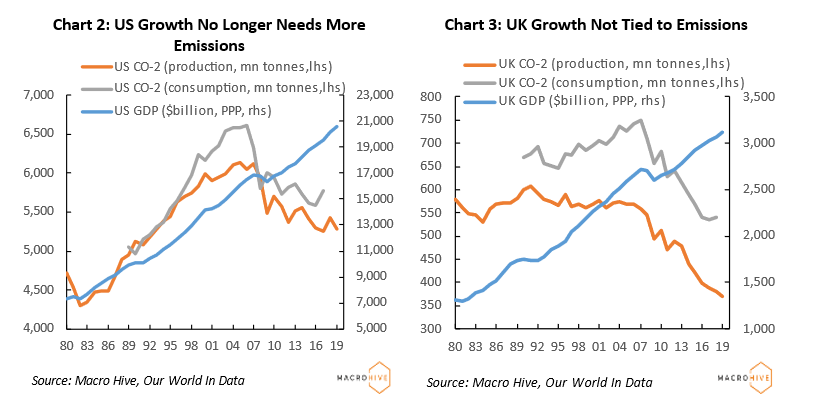

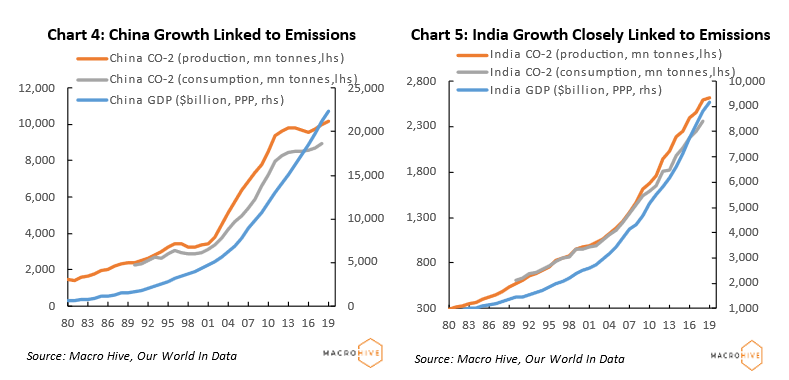

A question for any economy is whether it can continue to grow without more emissions. That is, is carbon a necessary by-product of economic growth? For advanced economies, the link is disappearing. The US’s carbon emissions peaked in 2006, but the economy has continued to grow ever since (Chart 2). We can see a similar picture in the UK (Chart 3). The move away from coal usage and towards natural gas in these economies has likely helped.

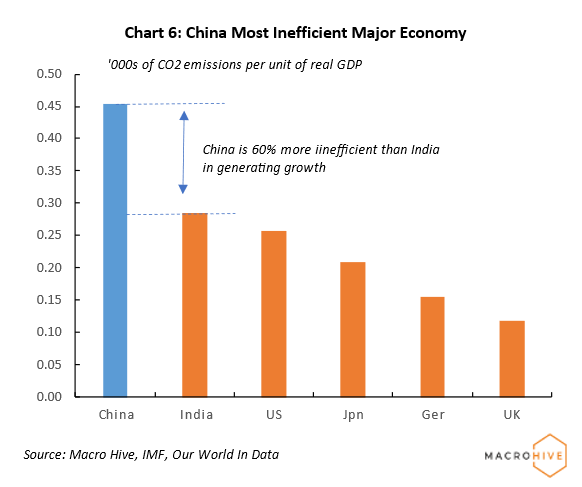

For China and India, we still see a link between emissions and growth (Charts 4 and 5). This likely reflects heavy coal use in the energy production of these economies. We can also assess the efficiency of generating GDP growth. China uses 60% more carbon to generate a unit of growth than India (Chart 6). Meanwhile, India uses only 10% more than the US. So, on this metric, China stands out as both the larger emitter of carbon and one of the most inefficient.

Ultimately, no strategy to manage climate change can succeed without China. Therefore, to assess the success of climate targets, all eyes should be on China’s energy production.

Bilal Hafeez is the CEO and Editor of Macro Hive. He spent over twenty years doing research at big banks – JPMorgan, Deutsche Bank, and Nomura, where he had various “Global Head” roles and did FX, rates and cross-markets research.