Summary

- The UK chancellor’s government spending outlay announced in October was unexpected, but that may be due to academic discoveries in recent years.

- Pioneering research highlights the large pro-growth benefits of spending policies in low growth and low interest rate environments.

- It also shows these policies decrease income inequality. Alongside higher growth, this could be a political advantage entering the next election.

Introduction

UK Chancellor Rishi Sunak surprised many with a larger-than-anticipated government spending stimulus in the Autumn Budget. This could signal a mindset change among policymakers. If not now, when? With subpar growth for a decade, a low cost of borrowing and the prospect of higher inflation, governments may seize this environment to change long-term growth trajectories.

In this Deep Dive, I explain why the chancellor is implementing the pioneering post-GFC research on the impacts of fiscal policy. This offers insight into the short-term growth prospects of the stimulus package and early evidence on why it may not have the lasting impacts the government wants. I find:

- Discretionary government spending policies have a positive short- and medium-term growth impact, especially when the policy rate is near zero, inflation is high, and growth is low.

- Those at the income distribution’s bottom end typically benefit most, but the income gain is only likely to boost short-term consumption and not affect long-term aggregate demand.

- In a UK context, the fiscal impulse is turning negative and so the GDP gains from this round of spending will be significantly lower than the 9pp gain experienced last year.

Fiscal Policy Pioneers

Literature on the macroeconomic effects of monetary policy is plentiful. But surprisingly, a framework for analysing fiscal policy was not created until the early 21st century. In 2015, pioneering fiscal policy expert Eric Leeper published ‘Fiscal Analysis Is Darned Hard’, explaining why it lagged monetary policy research by so many years. The reason is partly that central bankers have clearly defined macroeconomic objectives, like inflation targeting, while fiscal authorities do not. Distributional considerations and demographics, not growth, have mainly driven their choices.

The goalposts for governments are now changing. Monetary policy can no longer be relied on as the primary driver of growth, so, ever since the GFC, academics have been searching for a policy mix that governments can use to affect growth. Consequently, the fiscal multiplier literature has boomed. A multiplier is defined as the ratio of the change in output to the change in spending or taxes that caused it. A seminal paper by Valerie Ramey finds that for every additional 1% governments choose to spend, the economy expands by 0.8% – a multiplier of 0.8.

If Not Now, When?

Recent literature argues fiscal policy’s impact on growth will depend on (a) the type of policy being implemented, and (b) the conditions of implementation. This can help us rationalise Rishi Sunak’s decision to focus predominantly on spending.

On policy type, three main groups exist: taxes, consumption spending, and investment spending. On taxes, an aggregate rise in revenue, like that in the UK over the last year, negatively affects growth. The impact tends to start small, but after two years, a 1% unexpected rise in tax revenue could hurt growth by up to 2%. Conversely, a tax revenue drop tends to increase growth in the first year by 0.25%.

However, if the government wants growth, it should focus instead on spending – as Sunak has. This is because the growth potential in the first year can be three times higher than a tax-orientated strategy, even after controlling for the need to finance spending through higher taxes later. Investment spending is also pro-growth, but gains are generally felt over longer periods.

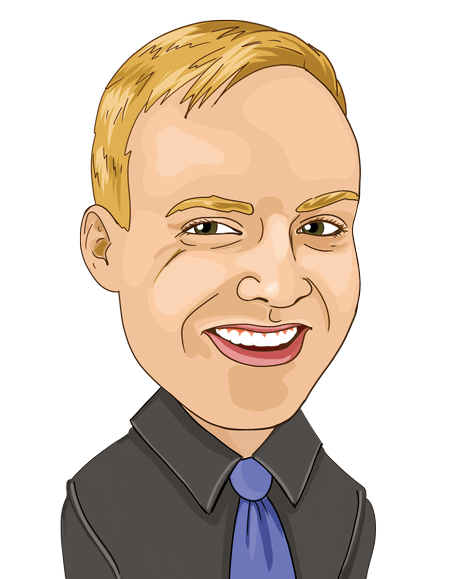

I show the UK fiscal multiplier for various government spending shocks since the 1970s on Chart 1. As expected, consumption and investment policies are pro-growth, with benefits peaking after 1.5 years. The benefits of an investment boost are also felt for many years. I also added individual and collective consumption multipliers. The former includes greater spending on health and education, which the current budget emphasises, and it has an even larger pro-growth effect.

Sunak’s choice of policy mix seemingly aims to maximise growth, especially in the short to medium term. The unconditional growth gains from his spending strategy will, on average, be quite high. However, the actual gains will be conditional on the state of the economy. And this is where recent leading academic research has likely helped inform his decision.

#1: Fiscal Multipliers at the Zero Lower Bound

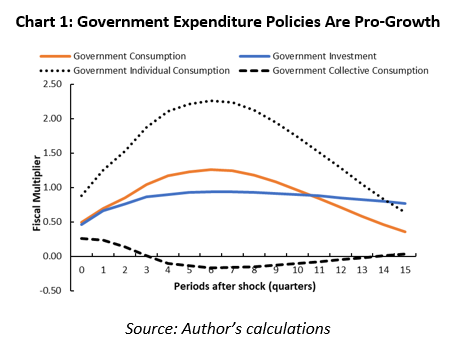

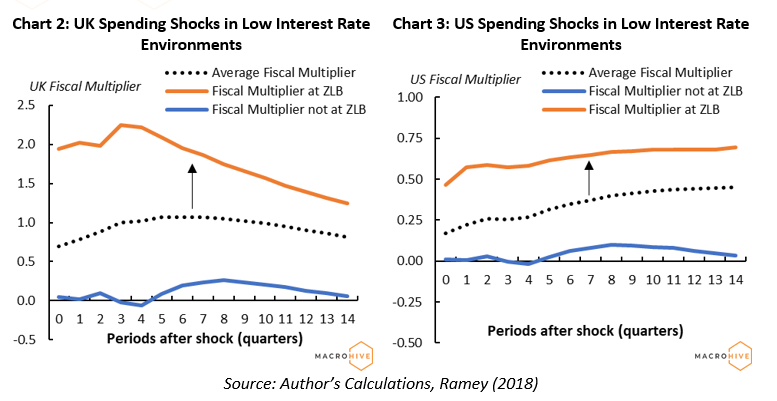

One heavily discussed area of the literature over the last decade is the effectiveness of fiscal policy when the central bank policy rate is near 0%. Following Ramey (2018), I simulate the GDP response to discretionary government spending shocks during periods when the zero lower bound (ZLB) constrains monetary policy. I graph the results for the UK (Chart 2) and US (Chart 3).

Both charts highlight just how effective fiscal spending is when the policy rate is at the ZLB. The GDP growth gains can be up to twice as large as the average. Moreover, a comparison across countries suggests that UK spending shocks have historically been better at stimulating growth than in the US.

#2: Fiscal Multipliers When the Fiscal Impulse Is Negative

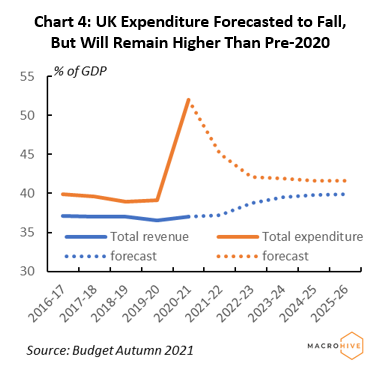

Despite the announced spending plan, UK fiscal policy will still tighten notably YoY (Chart 4). A typical measure of the fiscal stance is the Cyclically Adjusted Primary Deficit (CAPD), which takes the difference between government expenditures (less net interest payments) and revenues. Its change over time, after accounting for cyclical factors, is the ‘fiscal impulse’.

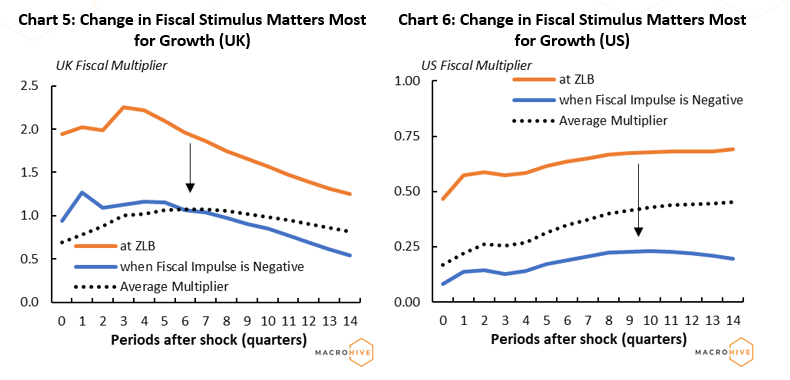

If we account for periods where the YoY fiscal stance of the government has turned negative, there is a notable reduction in the UK (Chart 5) and US (Chart 6) fiscal multiplier. Assuming we could otherwise have enjoyed a fiscal multiplier like the one at the ZLB (orange line), the expected GDP benefit is about 0.5 (blue). Meanwhile, this blue line is around 0.25 of the GDP gain seen during a positive fiscal impulse, like last year.

#3: Fiscal Multipliers During High Inflation Periods

The effectiveness of government spending is likely to be affected by the level of inflation and to influence inflation itself. Higher inflation reduces real incomes and, if consumption habits stay the same, it reduces the savings rate and so demand. If government spending boosts household incomes (as we shall see in the next section), can it have a larger influence on growth in high inflation periods?

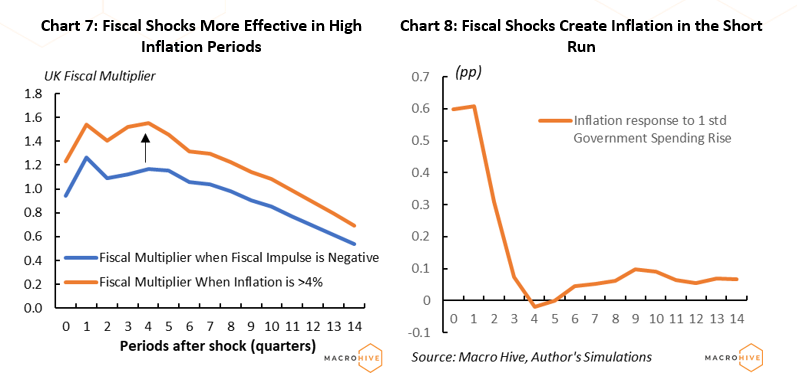

Yes. Looking at the impact of spending shocks on GDP in the UK during periods where inflation was above 4%, the growth gain is larger (Chart 7). However, this is likely to put additional upward pressure on prices (Chart 8). I use the US as an example. Any spending shocks between 1890 and 2015 that happened when inflation was already high further increased inflation by up to 0.6pp in the first quarter. However, their inflationary impact disappeared after one year.

Secular Stagnation: A Long-Run Perspective

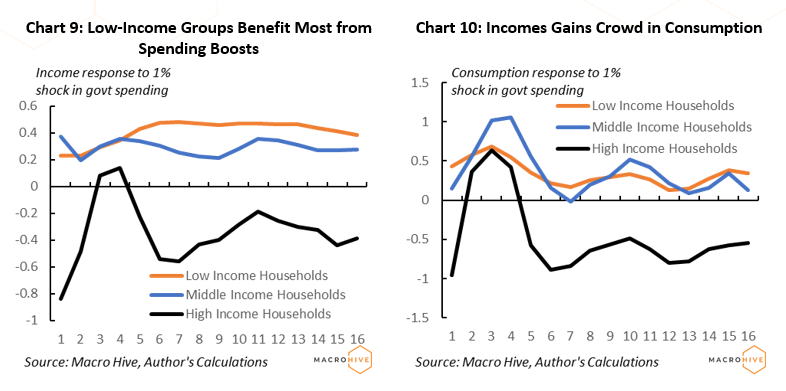

Not everyone benefits equally from government spending shocks, even if the shocks are not intended to redistribute income. By definition, a spending shock is unexpected, meaning it does not include the government’s automatic efforts to redistribute income, like income tax or unemployment benefits. So, there is no guarantee shocks benefit the poor. Reassuringly, though, the latest research shows they do (Chart 9).

Take, for example, a 5% government spending shock. This would increase the incomes of the poorest individuals by on average 1-2%, and this income gain persists. Middle-income households also benefit, while society’s highest earners predominantly bear the costs. So, government spending policies traditionally boost growth and reduceincome inequality. Conversely, periods of austerity have been shown to increase income inequality.

Why is this important? From income and consumption, we can derive the behaviours of households to government policies. Low-income households also increase their consumption in response to a government stimulus (Chart 10). Spending increases by more than income in the first few quarters, especially for middle-income households.

The results have important implications. Rising inequality is a well-cited reason for the secular decline of interest rates and growth. As we have seen, even fiscal policies that do not prioritise redistribution tend to reduce inequality, and so governments may be able to help reverse this structural issue restraining growth. If they could, policies should be able to alter the savings rate.

The results suggest this may not be the case. Both low- and high-income households alter their consumption in a similar way to their change in income. So, low- and middle-income households consume all the additional income, and high-income households adjust their consumption downwards when footing the bill. On aggregate then, even over four years, spending shocks appear not to change the savings rate, meaning they are unlikely to affect long-term aggregate demand.

Bottom Line

Fiscal policy research has improved significantly over the last decade and is highlighting the important role governments can play in stimulating growth. Their impact was especially felt during the pandemic. A recent study found UK growth in 2020 was around 9pp higher than if fiscal support had not happened.

Yet not all stimulus packages are equal. Their growth impact will depend on the type (e.g., investment, health, military, etc.) and the state of the economy. This Deep Dive has shown the current environment is conducive to higher returns, even with the fiscal impulse turning negative.

In the short run, greater-than-anticipated discretionary spending should reduce inequality, boost growth and increase inflation. Over the longer term, though, these policies’ impact on aggregate demand will most likely fade, although more slowly if policies are orientated towards investment.

Sam van de Schootbrugge is a Macro Research Analyst at Macro Hive, currently completing his PhD in international finance. He has a master’s degree in economic research from the University of Cambridge and has worked in research roles for over 3 years in both the public and private sector.