Summary

- The Baltic Dry Index is published daily. But for most investors who are not steeped in the logistics industry, it is one of those more obscure financial market indicators that only surfaces from time to time – mostly when it makes some dramatic move.

- It measures the average cost to ship dry bulk freight across 20 ocean routes. Its movements may reflect shifts in commodity prices, arcane shipping technicals, changing economic fundamentals, or some combination of all these.

- This article reviews the origins of the BDI, its performance over time, its key drivers, its economic significance, and thoughts on how to trade it.

What Is the Baltic Dry Index?

Baltic Dry Index is a shipping and trade index issued daily by the London-based Baltic Exchange. Often shortened to the BDI, the Baltic Dry Index is a composite of the Capesize, Panamax and Supramax Timecharter Averages. The BDI index measures the cost of transporting raw materials like coal and steel around the world, or more specifically, the demand for shipping capacity against the supply of dry bulk carriers.

Market Implications

- Understanding the nature of the Baltic Dry Index can help investors discern whether and how the freight shipping market is affecting the global economy.

Introduction

The Baltic Dry Index (BDI) is one of those more obscure financial indicators that turn up in the financial press when freight shipping rates break out of comfortable well-established ranges. Unfortunately, there is often little accompanying analysis to help investors decode what is driving these changes and how to capitalize on them. This article aims to help investors understand the BDI, think through what changes in it might mean, and learn how to take advantage of them.

A Storied History

If “Baltic Dry Index” sounds a bit like something from a bygone era, you wouldn’t be too far off. It dates to 1744, when businessmen and shippers involved in trade and shipping in the Baltic Sea area started meeting regularly at the Virginia and Baltick Coffeehouse in London to exchange news, trade securities, and do shipping deals. As global commerce grew with the emerging industrial revolution in the 19th century, the Baltic became a more formal organization. It set rules for trading and transacting a wide range of raw materials. It started compiling pricing information on various commodities and disseminating them in an early version of indices. By the second half of the 19th century, it was becoming more international, and its scope expanded to include agricultural commodities.

Enjoying this Explainer? Sign up to our free newsletter for more.

Today’s organization took form when the Baltic and the London Shipping Exchange merged to form the Baltic Mercantile & Shipping Exchange Ltd in 1900. During the depression years, the Baltic Exchange moved away from trading commodities to focus more on shipping and ship chartering, serving as intermediaries between ship owners and merchants around the globe.

In 1985, the Baltic Exchange started compiling the Baltic Freight Index for dry bulk cargo on defined ocean routes. It polled shipbrokers daily on the cost to ship cargo and compiled them into an index. In 1999, the BFI evolved into today’s Baltic Dry Index. The Baltic Exchange also developed freight derivatives, in particular the freight forward agreement (FFA) that allows shippers and merchants to hedge and lock in the cost of shipping commodities.

Today the Baltic Exchange is a key player in the global freight shipping market, compiling and disseminating information about the industry and freight derivatives. In addition to dry bulk cargo, the Baltic Exchange is also active in a wide range of other types of cargo, including tankers, container ships, and even air freight.

What Is Dry Bulk Cargo?

Dry bulk cargo is commodities that are shipped in loose unpackaged form. The primary bulk commodities are iron ore, coal, grains, bauxite/alumina, and phosphate rock. Other types include cement, forest products, some steel products, copper, and other base metals such as lead and nickel.

Bulk cargo is distinct from general cargo, which refers to cargo shipped in some packaged form, whether in sacks or palettes or some other organized or grouped manner.

Dry bulk cargo does not include tankers that ship oil, refined products, or chemicals; container ships; or roll-on ships, which carry vehicles that can be driven or rolled on board. The Baltic Exchange has separate indices for tankers and container ships.

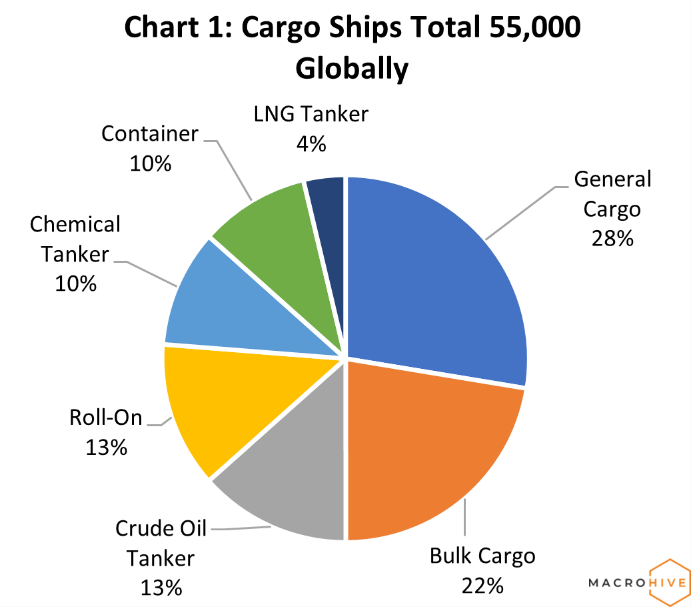

Dry bulk ships account for about 22% of the global merchant fleet (Chart 1). And they account for 30% of the total value of $14 trillion of cargo shipped annually.

Source: Macro Hive, Statistica

What Does the BDI Measure?

The BDI is a summary indication of the cost to ship bulk cargo over 20 standard ocean routes (the Appendix has a list of routes).[1] In other words, it indicates dry bulk shipping rates. The Baltic Exchange compiles the daily hire rate in USD from international shipbrokers for three types of bulk freight ships.

- Capesize – Ships that carry 120,000 – 400,000 deadweight tons (dwt) of cargo. They are used primarily for iron ore and coal. They are too large to travel through the Panama Canal and must travel around the Cape Agulhas or Cape Horn.

- Panamex – Ships designed to traverse the Panama Canal. They can carry 60,000 -120,000 dwt of cargo.

- Supramax/Handymax – Ships that can carry 40,000 – 60,000 dwt of cargo.

There is a fourth smaller class of ships, Handysize, but the BDI index does not include them. There are also various sub-classes of ships within these broad categories designed to be compatible with the Suez Canal and various ports worldwide.

The shipping quotes are combined into the overall index with a 40% weighting for Capesize, and 30% each for Panamex and Supramax. These weights are based on the volume of cargo (in dwt) shipped on each type.

What Is the Economic Significance of the BDI?

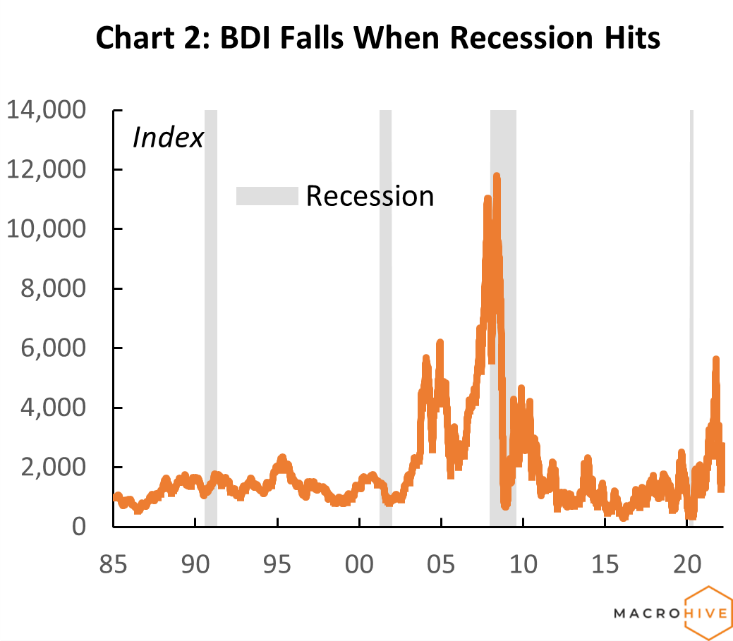

The BDI is a fundamental leading indicator of global economic activity and a technical indicator of freight industry capacity. For much of its history, the BDI has traded in a range between 1000 and 2000 (see the Baltic Dry Index chart below, Chart 2). It typically falls as recessions approach and leads the recovery out of recession. As such, it is a useful leading indicator of global economic health.

Source: Macro Hive, Bloomberg

The supply of bulk ship capacity is highly inelastic over short- to medium-term horizons. It takes two to three years to order, build and put a new large bulk carrier into service. Consequently, changes in the demand for shipping bulk cargo can have outsized impacts on the index. That was evident in 2006-2008 when China embarked on a massive infrastructure program to prepare for the Olympics. To make matters worse, as oil prices rose to unprecedented levels, shippers slowed their vessels to conserve fuel. When the Great Financial Crisis hit (after the Olympics), commodity demand collapsed, along with the BDI.

The BDI jumped six-fold last year as the global economy recovered from the Covid slowdown, spurring a sudden demand for raw materials. Meanwhile, congested ports meant that bulk carriers had to wait weeks or more to load and unload cargo, effectively curtailing the supply of available ships.

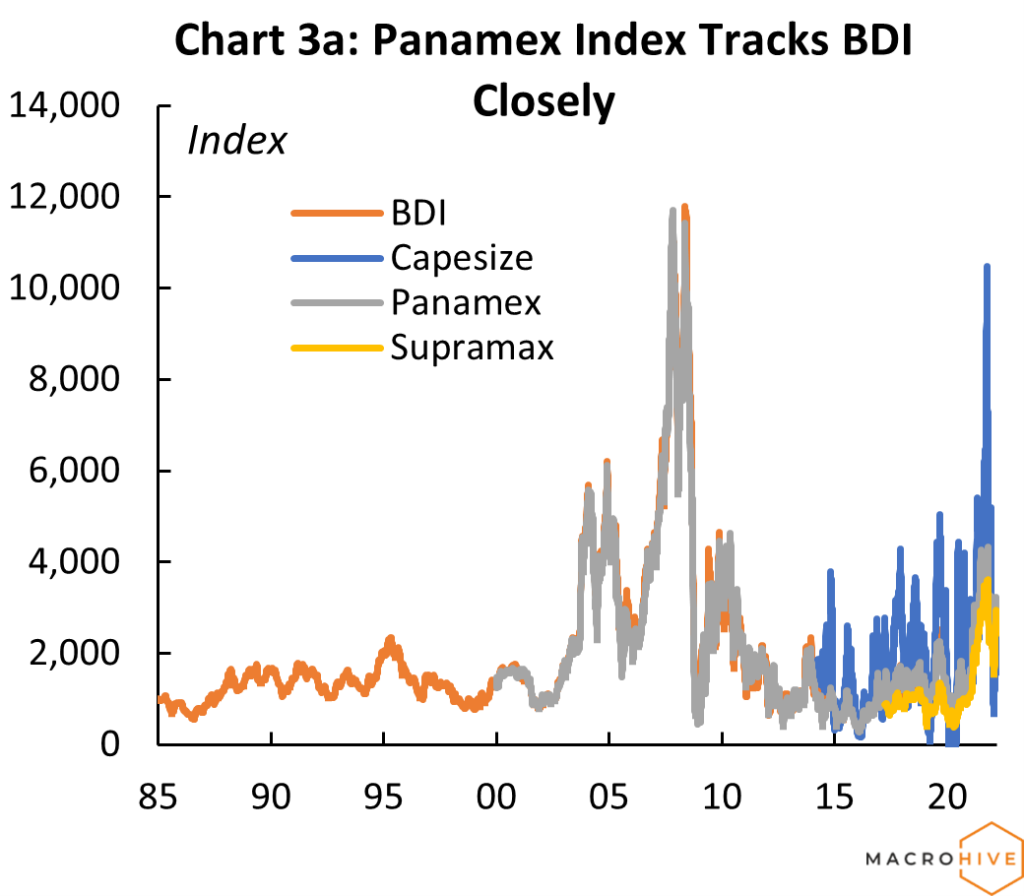

Subindices Tell a Story Too

Over the years, the Baltic Exchange started publishing subindices for each of the BDI vessel types (Charts 3a,b). The Panamex Index debuted in early 2000, followed by Capesize in 2014 and Supramax/Handymax in 2017. Over time, the Panamex index has mostly closely tracked the BDI. The Capesize has been the most volatile.

Chart 3b shows the period that the Capesize has been published and rebased to match the BDI at inception to better illustrate relative volatility. When demand for commodities is high, there is a strong bid for Capesize ships; freight prices rise both because there a fewer of them and because they are the most efficient way to ship large volumes. Likewise, when commodity demand softens, people do not need the volume that Capesize offers. There have been brief periods when the Capesize index dropped below zero, implying that shippers were losing money to keep their ships busy.

Recently, the baltic index has been rising, primarily because of the Panamex Index. The Capesize Index is only just coming off a cyclical low. This is typical as the Capesize tends to react to a rising Panamax index with a lag.

Source: Macro Hive, Bloomberg

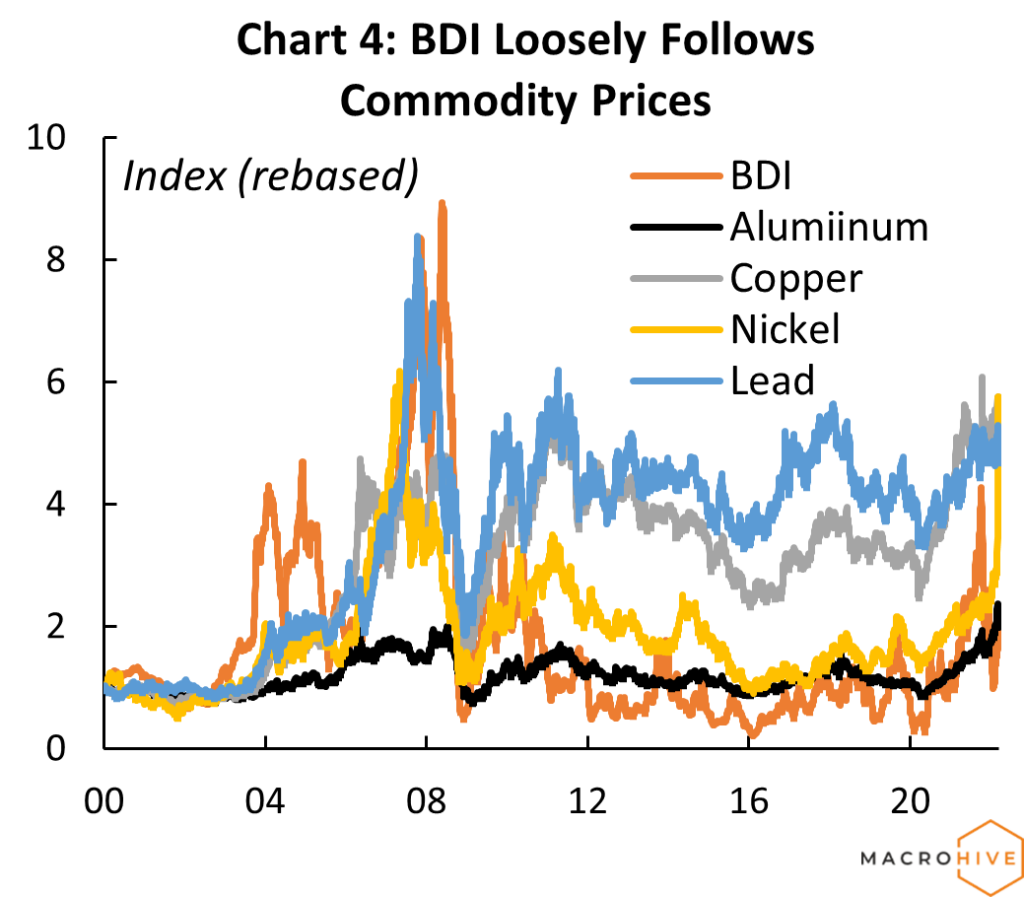

The BDI Is About Dry Bulk Shipping Rates, not Commodity Prices

Intuitively, you might expect a close relationship between commodity prices and the BDI. After all, when demand for some raw materials rises, there will usually be a higher demand for shipping bulk commodities. There is academic work that suggests that commodity prices do help drive the BDI, at least in the short run.

But in comparing the BDI to several major bulk commodities, it is also apparent the BDI is surprisingly independent of commodity prices (Chart 4). The BDI and commodities did rise and fall roughly in line with each other during 2006-2008 and in 2021. But during 2004-05, the BDI twice jumped to over four times its 2000 level while commodities only trended gradually higher. After the Great Financial Crisis, copper and lead prices remained elevated, and nickel only gradually declined. But by 2011, the BDI settled in a narrow range near the 1000 level until 2021. The reason was that the 2006-2008 experience led to a substantial increase in shipbuilding, such that new supply of dry bulk shipping capacity stayed in line with rising demand for commodities and shipping.

During more extended slowdowns, shipowners may remove ships from service or scrap older and more inefficient ships. This helps keep shipping capacity in line with demand.

The key point here is that the BDI is primarily a measure of shipping rates at a point in time. It is not a proxy for commodity prices.

Source: Macro Hive, Bloomberg

The BDI Versus Other Shipping Indices

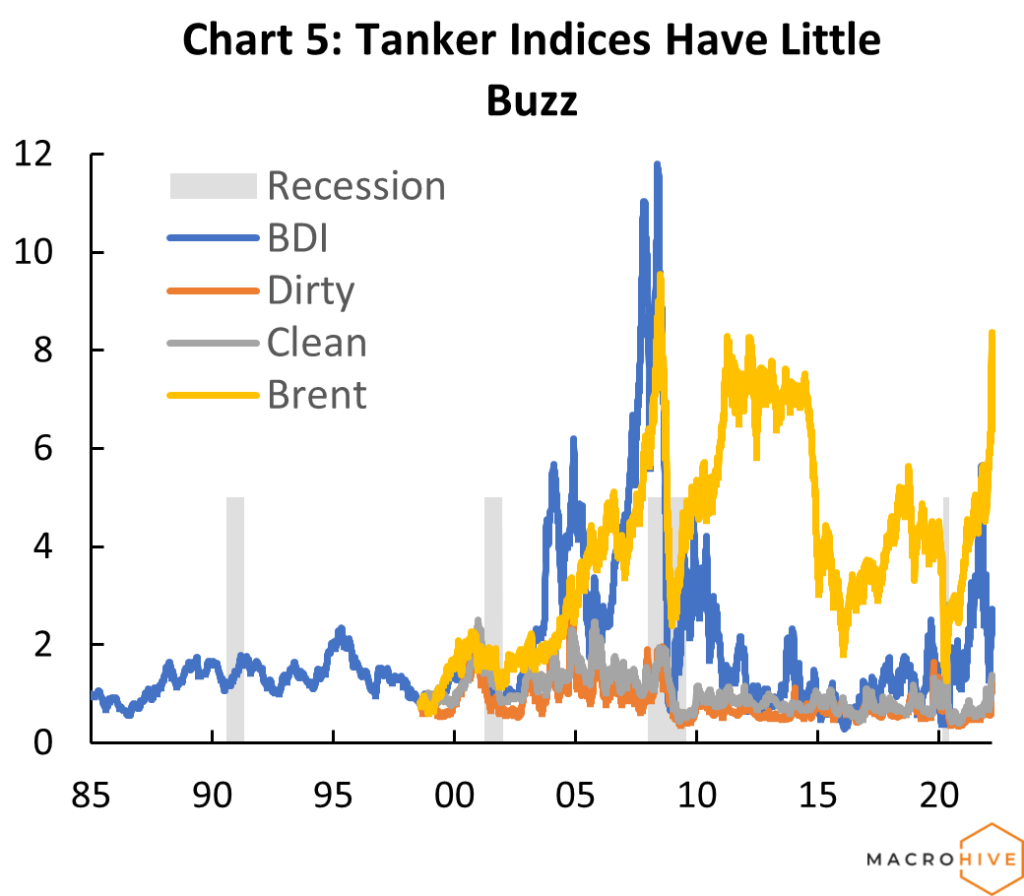

The Baltic Exchange publishes several other lesser-known freight indices, including two tanker indices and, more recently, a containership index. The containership index is not available on Bloomberg, but the tanker indices have been published since 1997 (Chart 5).

The “Dirty” index covers tankers that transport crude oil; the “Clean” index is for refined products.

What stands out is the lack of volatility in the tanker indices relative to the BDI and the lack of discernable relationship with oil prices.[2] We have not seen studies explaining this differential performance, but there are a few possible explanations.

First, the growth in global demand over time for fossil fuels has been more steady than for various dry bulk commodities. Second, OPEC (for the most part) has worked to keep oil supply growth roughly in line with growth in demand. This allows refiners and shippers to increase the supply of dirty and clean tankers as volumes grow. Third, tankers have some ability to switch from dirty to clean cargos and vice versa, as supply/demand dynamics shift within the dirty and clean sectors. Fourth, it is easier to keep tankers in service. Tankers can be loaded or unloaded within a day or so and prepared for a new voyage within days. Dry bulk ships require a week or more to load or unload cargo, and it can take weeks to clean and prepare a ship for new cargo.

Investors and the financial press pay far more attention to the BDI than to other freight indices. Apart from having been around longer, it is far more dynamic and exciting than its tanker cousins and makes for more dramatic headlines. Unfortunately, these stories rarely provide a more detailed analysis of whether the BDI is being driven by commodity market dynamics or shipping market technicals. That means investors need to do more digging to figure out what it means and how to position themselves accordingly.

Can I Trade or Invest in the BDI?

The BDI is not an investable index. It does not trade on any exchange. There is no underlying security or securities that comprise the index. Rather it is, by construction, an index of average dry bulk shipping quotes over some 20 ocean routes obtained from a global network of shipping agents and brokers.

Investors can use the BDI to help trade or invest in related financial instruments. We can offer the following summary for interested readers.

The most direct instrument is forward freight agreements, which cover various shipping routes. The Baltic exchange publishes a variety of spot freight rates, which are the basis for settling these contracts monthly.

Various futures exchanges also offer freight futures contracts, including the European Energy Exchange and the Singapore Exchange.

Alternatively, investors can invest in the BDI more indirectly through shipping company equities.[3] We caution that shipping profitability depends not only on the level and trend of the BDI but on what is driving it. For example, the BDI may be rising because of higher oil prices – but profitability may fall if shippers can’t pass on that higher cost. Another strategy is going long or short oil depending on whether the price of oil is rising or falling; the idea is a rising BDI implies more shipping and higher demand for fuel. More generally, investors can monitor the BDI for a leading indicator of whether a recession or economic boom is coming, although these signals can be obscured by shipping technicals.

Closing Remarks

This article is aimed at investors for whom the BDI is mostly off their radar screen and then are left wondering what to make of it when it pops up in the financial press headlines.

Our primary message is this: the BDI is a good and reliable measure of what it purports to measure – namely, average shipping costs of dry bulk cargo over 20 standard ocean routes. When it comes to interpreting it, science soon segues into art. Whether it is signaling something about the commodities market or global economic conditions, or simply the shipping market technicals, will always be the question of the day.

If we have given investors some perspective on how to interpret the BDI, we have done our job.

Shipping Routes Used to Determine the Baltic Dry Index

| Capesize (120,000+ dwt) | Panamax (60,000 – 120,000 dwt) | Supramax (40,000 – 60,000 dwt) |

| Gibraltar/Hamburg transatlantic round | Skaw-Gib transatlantic round voyage | Canakkale trip via Med or Bl Sea to China-South Korea |

| Continent/Mediterranean trip China-Japan | Skaw-Gib trip HK-S Korea incl Taiwan | US Gulf trip to China-south Japan |

| China-Japan transpacific round voyage | HK-S Korea incl Taiwan 1 Pacific round voyage | North China one Australian or Pacific round voyage |

| China-Brazil round voyage | HK-S Korea incl Taiwan trip to Skaw-Gib | North China trip to West Africa |

| China via Australia/Indonesia or South Africa or Brazil or US West Coast to UK/Continent/Mediterranean | Dely Spore or Busan (during US grain season) round voyage via Atlantic | West Africa trip via east coast South America to north China |

| Skaw-Passero trip to US Gulf | ||

| US Gulf trip to Skaw-Passero | ||

| South China trip via Indonesia to east coast India | ||

| West Africa trip via east coast South America to Skaw-Passero | ||

| South China trip via Indonesia to south China |

FAQ

→ How to interpret the Baltic Dry Index?

You should interpret the Baltic Dry Index as a reliable indicator of average shipping costs of dry bulk cargo over 20 standard ocean routes. Some investors believe it indicates shipping market technicals. We would not interpret the BDI as a proxy for commodity prices.

→ What is BDI?

The BDI is an acronym that stands for the Baltic Dry Index. It is a composite shipping and trade index issued daily by the London-based Baltic Exchange. The BDI is a measure of the cost of transporting raw materials worldwide.

→ How to trade the Baltic Dry Index?

It is possible to trade the Baltic Dry Index using forward freight agreements, which cover various shipping routes. The Baltic exchange publishes a variety of spot freight rates, which are the basis for settling these contracts monthly. It is impossible to trade the Baltic Dry Index directly because it is not an investible index.

→ What is a Capsize vessel?

A Capsize vessel is the largest class of dry cargo ship. It can carry all types of cargo, including iron ore and coal. It is called a Capesize vessel because it is too large to travel through the Panama and Suez canals and so must traverse the Capes of Good Hope and Horn.

→ What is the size of Supramax?

The size of Supramax is 50,000 to 60,000 DWT. It is a large bulk carrier that usually has five cargo holds and deck cranes. This is different from a Panamax ship. A Panamax ship is a vessel that is designed to travel through the Panama Canal.

What does BDI stand for?

BDI stands for the Baltic Dry Index.

What is dry shipping?

Dry shipping is the transportation of dry cargo by ship in an enclosed container. Dry cargo includes commodities such as metal ores, coal and grains but excludes oil, gas, chemicals, etc. It is ultimately a form of commodity shipping.

- The BDI only covers ocean routes; it does not cover shipments on the US Great Lakes, which account for about 5% of global dry bulk shipment volume. ↑

- One notable exception was April 2020, when oil prices plunged, sending West Texas Intermediate futures to negative 37.63. Demand disappeared in the weeks after the Covid lockdowns hit and pipeline operators suddenly chartered tankers to store excess supply, causing tanker rates to spike. ↑

- One example of a shipping company equity is the SHIP stock, which trades on the NASDAQ. It is Seanergy Maritime Holdings Corp, an international shipping company that provides marine dry bulk transportation services through the ownership and operation of dry bulk vessels. Certain outlets offer a SHIP stock forecast. Another example is the Dryship stocks (occasionally mistyped as Dry ship stock), which is a dry bulk shipping company based in Athens. However, Macro Hive does not offer recommendations for these stocks.

Great insights. Thank you.

Although shipping companies equities are strongly correlated with the BDI, I think it’s also important to note their dependency on the supply side. For Capesize, new regulations are causing ship scrapping to increase, and the uncertainty (both about demand and commodity prices) is helping their orderbook (% of ships under construction compared to those in use) to be at the lowest level for +20 years.

This causes higher rates, especially with increasing oil prices that cause ships to slow down (with older vessels without scrubber technology being the most vulnerable to this).