Economics & Growth | Monetary Policy & Inflation | US

Economics & Growth | Monetary Policy & Inflation | US

Shortages are everywhere, and US businesses are scrambling to meet unfulfilled demand. Yet historically, periods of excess supply often follow those of excess demand. Could this happen again?

In 1961, systems analyst Jay Forrester coined the ‘bullwhip effect’ to describe supply chain inefficiencies. Just like the amplitude of a whip increases further down its length, demand signals become noisier further upstream on the supply chain.

Versus the 1960s, today’s complex global supply chains have much greater scope for bullwhip effects. And the pandemic has only increased the risks, as businesses attempting to rebuild inventories could easily be mistaken for increasing consumer demand. This creates noisy signals for upstream producers, which are likely to miss a demand turning point.

Also, for many critical commodities, production is lumpy and hard to turn down. For instance, semiconductors, a key upstream input, require large-scale, capital-intensive foundries. Once operating, room for adjusting production volumes is limited. Governments worldwide have been pressuring chip manufacturers to increase production, creating a good chance of a glut next year. Fears of a supply glut and lower prices next year have driven recent KOSPI underperformance.

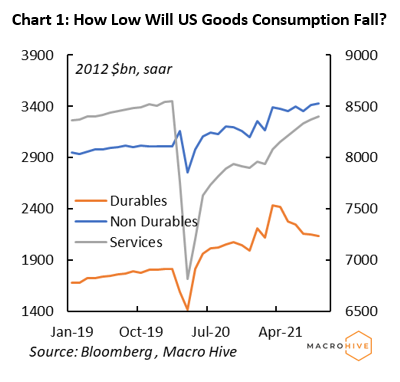

But perhaps the biggest risk of an inventory glut is consumer demand. Before the pandemic, goods consumption represented about 35% of overall consumption. In September, it represented 40%, down from a peak of 42% in March. In real terms, September goods consumption was still up 15% from February 2020, when pre-pandemic it typically grew by 3.5-4% a year. Also, personal disposable income started shrinking in August. And consumption growth has become dependent on further declines in the savings rate, which is already back at pre-pandemic levels.

The bottom line is that risks to goods consumption are tilted to the downside, and a demand deficiency could easily surprise producers.

Left with an inventory glut, producers would likely lower prices. That could have cumulative effects along supply chains, especially as growth will likely slow next year. The long-awaited post-pandemic deflation would finally happen.

Deflation could make Fed policies less hawkish. But it would not necessarily be positive for equity markets. US corporate profits have remained historically high in real terms since Q3 2020, reflecting more pricing power and margins at historical highs than large volumes. A loss of market power caused by an inventory glut could therefore come with rapidly declining profits and increasing real wages as nominal wages would adjust with a lag, which would be negative for equity prices.

There are already signs of weakening excess goods demand. In the manufacturing PMI, the backorder index has been falling since June, and the new orders index plunged in October. The Baltic Dry Index, a measure of the cost of shipping raw materials such as coal and steel, is down more than 55% from its early October peak. The cost of shipping containers from China to the West Coast of the US has been falling since mid-September. Ultimately, coming off the sugar high of unprecedented fiscal and monetary easing will be a bumpy process for businesses, and swings in inventories and profits are likely.

Spring sale - Prime Membership only £3 for 3 months! Get trade ideas and macro insights now

Your subscription has been successfully canceled.

Discount Applied - Your subscription has now updated with Coupon and from next payment Discount will be applied.