Global | Politics & Geopolitics

Global | Politics & Geopolitics

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine dominated markets over the last year, setting in motion regime changes on multiple fronts. NATO members have united, Europe has rejected pacifism and divested from Russian energy, and the ECB has shifted from a negative rate regime to a restrictive one. Few could have predicted any of these outcomes before the invasion.

History suggests such upheavals often propagate new, unexpected risks. It will therefore be critical for investors to monitor geopolitics in 2023.

Both domestic and cross-border issues have plagued Iran in recent months. Protests against the government grew exponentially in September 2022, gaining strong traction in provinces with large ethnic minorities (particularly Kurdish and Azerbaijani). Meanwhile, external threats to the nation appear to be rising. That could spark conflict.

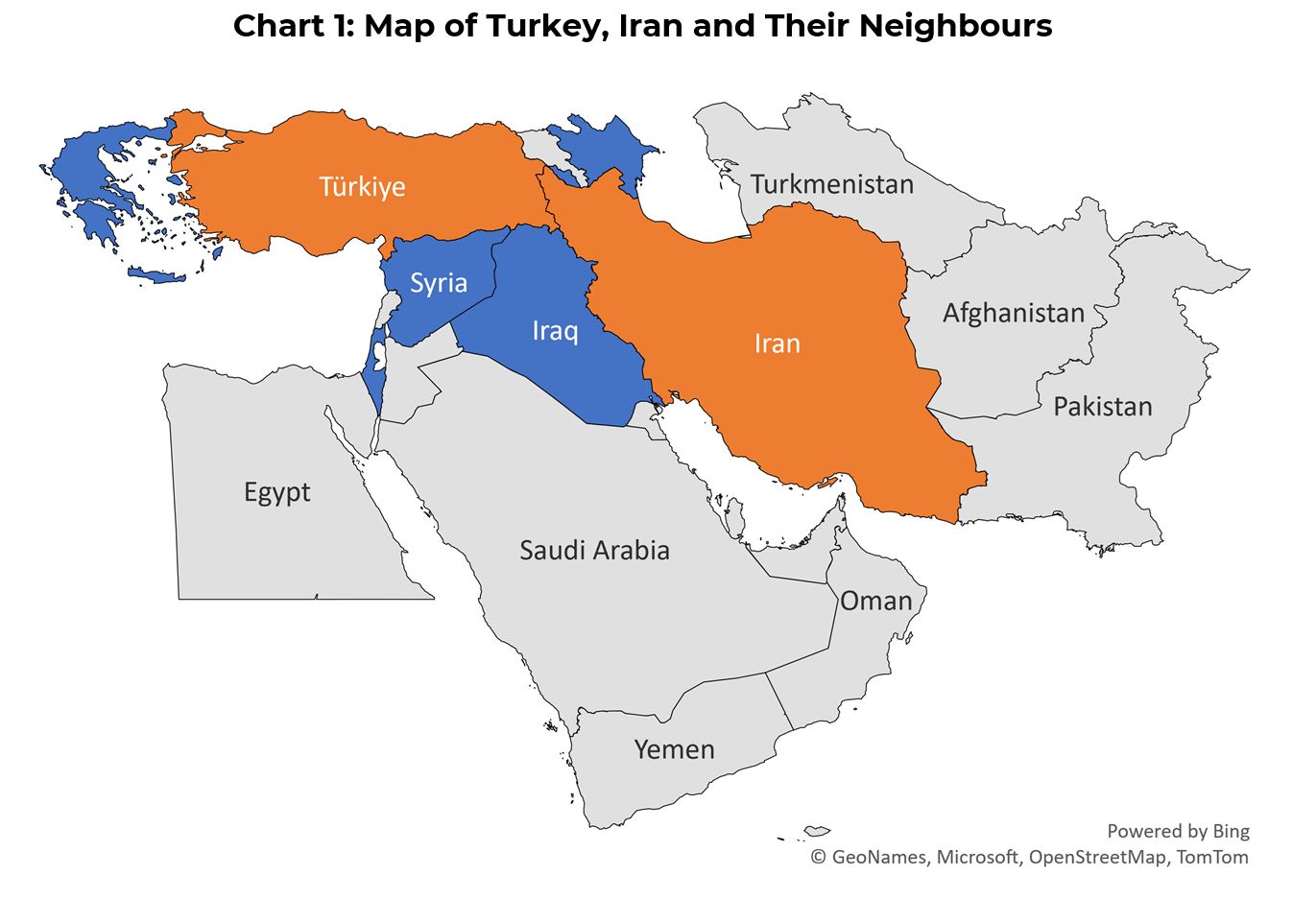

Iran sits on significant oil reserves and plays a major geopolitical role in the region, supporting governments in Syria and Iraq and aiding an increasingly isolated Russia. Given global oil production may fail to meet demand, some in the West saw Iran as a potential avenue to increase supply. That possibility now looks increasingly unlikely.

Domestic issues risk triggering regional flashpoints. The Iranian government may look to externalize problems, while local rivals try to hit the regime when it is unpopular and isolated.

Israel’s Attack on Iranian Drone Facilities

The recent drone strikes on an Iranian military facility in the country’s north west have raised tensions on all fronts. Anonymous US sources suggest Israeli involvement. Complicating matters, the drones’ short range suggest they may have been launched inside Iran. Tehran has previously accused Iranian Kurds of cooperating with Israel to attack its infrastructure.

A Response Into Iraqi Kurdistan?

There is a well established history of Iranian aggression against Iraqi Kurdistan. Iran struck US bases in Iraq (including Kurdistan) in January 2020, in response to the US assassination of an Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Major General.

Iran-affiliated groups struck the region’s capital, Erbil, again a year later. Following this was another IRGC strike on Erbil last March on an alleged Israeli base. Later Turkish and Iraqi sources suggested it was to deter the region’s plans to supply gas to Europe.

Finally, last September, the IRGC fired artillery, missiles and drones into the region on the back of the protests, which it claimed separatist Iranian Kurdish forces there had started.

Iran and the IRGC’s willingness to escalate across their western border is important as the region is a major source of Iraqi hydrocarbons. Pipelines there provide oil to Turkey, and there are plans for gas pipelines too. Turkey has strong interests in the area, having established at least 40 bases in the region following numerous incursions (most recently in April 2022). Iranian military aggression there could provoke a response from Turkey.

Tensions with Azerbaijan

An alternative flashpoint could be to the north, along the border with Azerbaijan. Tensions with the small, gas-rich country have a long history. The Azeris are a Turkic people and share close relations with Iran’s regional rival, Turkey (extending to mutual security guarantees). Official Azerbaijan comments around the sizeable Azeri minority in northern Iran present an ongoing headache for Tehran, as do their strong relations with Israel.

Tensions have been high since Azerbaijan’s success in the 2020 Second Nagorno-Karabakh war, during which Iran supported Armenia. Since then, Iran has performed repeated military exercises in the border region, while Azerbaijan has arrested Iranian scholars and accused Iran of plotting a regime change.

There was an escalation in January when a gunman opened fire at the Azerbaijani embassy in Tehran, killing one guard and wounding two others. Azerbaijani government-affiliated media accused Iran of being behind the attack, and Azerbaijan has since evacuated its embassy staff and arrested men it accuses of being part of Iranian spy rings.

Azerbaijan’s Importance for EU Energy Plans

Since the war in Ukraine began, Azerbaijan has become much more important as a hub for gas (via Turkey) to Europe. The EU imported 8 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas from Azerbaijan in 2021 (c.3% total natural gas imports), but aims to raise this to 27bcm by 2027 (c.10%).

We have warned previously that the EU’s efforts to diversify away from Russian energy will leave the bloc exposed to new instability. The Caucasus is a prime example.

At this stage, tensions are not boiling over, but the Israeli drone strike has added to concerns. Azerbaijan has been increasingly courting Israel, and given the embassy attack and the drone attack occurred only a day apart, conclusions may be drawn from Tehran that there is a connection.

Iran’s explicit military drone support for Russia means attacks on its facilities are unlikely to receive international condemnation (Ukraine has pretty much condoned them). Russia’s regional clout has also reduced. It acts as peacekeeper between Armenia and Azerbaijan but has recently been accused of ineffectiveness. This could lower the potential costs to Azerbaijan undertaking provocative action in the region.

Turkey’s presidential and parliamentary election on 16 May (brought forward from June) will be a watershed moment. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has held power for 20 years, during which time he has consolidated his power over the government, judiciary and (especially post-2016 coup) the military. But his use of authoritarian powers to suppress opposition figures could well backfire.

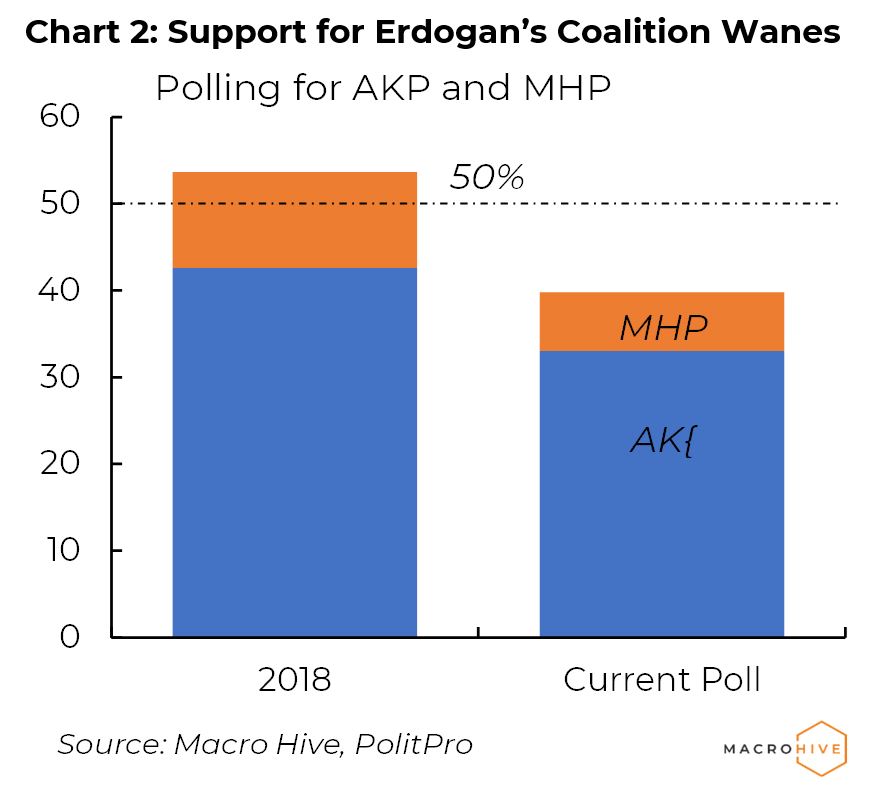

Polling for the presidential vote has not been updated since last July, at which time Erdogan was set to lose to almost every potential head-to-head opponent. More recent parliamentary vote polling suggests support for his party (AKP) and coalition ally (MHP) continues to drop (Chart 2).

The fallout from the recent earthquake in southern Turkey could be crucial. In 1999 when an earthquake struck the country’s west, the incoherent response severely reduced support for the then government and in turn helped Erdogan’s AKP gain power.

Erdogan’s quick announcement of a three-month state of emergency in the worst-hit regions suggests his action will be far stronger, and his media control should ensure favourable coverage.

Yet there are already signs of discontent with the response. For instance, the decision to block Twitter access to prevent ‘disinformation’, has come under criticism for impairing coordination of disaster relief.

If Erdogan cannot rebuild his popularity soon, he may delay the election or use an external distraction. Only a few months ago, he threatened Syria’s Kurdish region with invasion. The earthquake’s fallout limits resources for such an excursion now, but it remains a risk. Back in 2015, between the inconclusive June and the snap November elections, terrorist attacks in Turkey culminated in ground operations against Kurdish rebels and airstrikes into Syria and Iraq. Then, opposition figures claimed it was an attempt to curb support for their parties. Either way, the AKP performed far better in the November elections and the coalition clinched a majority.

Given the importance of the Middle East (the most likely direction of new Turkish military operations), a resumption of cross-border violence could further destabilize the region. And it could further isolate a Turkey already willing to lash out at its Western allies. Turkish threats towards EU and NATO member Greece are unlikely to escalate, but perceived fracturing within NATO could embolden its enemies.

The invasion of Ukraine is nearing its first anniversary, and Russia has gained little. It is now widely expected to engage in a major spring offensive. Ukraine has managed to hold Russia close to its pre-2022 occupied regions since its late 2022 counter offensive. It now seeks to shore up material support from the West to avoid being pushed back again.

Western Allies Promise Advanced Tanks and Air Defense Systems

Ukraine has stated it needs 300-500 extra tanks to retake occupied territories. They have previously received Soviet-era, 2nd gen. main battle tanks (MBTs). However, Western allies now promise around 155 3rd gen. MBTs, as well as 178 2nd gen. MBTs.

The announcement of tank deliveries has garnered strong headlines, but the reality on the ground could be subdued. Delivery dates have yet to be confirmed (the US will send newly built tanks rather than stockpiled ones, so delivery could be months). And some commitments remain nebulous.

Training time for Ukrainian crews and additional support requirements to mitigate Russian airpower could further extend the time before they play a role. More modern air defense systems have been promised (including Patriot batteries), but their delivery will take time too.

Requests for Modern Fighter Jets Gain Traction

Through 2022, Ukraine received around 18 legacy Soviet-era attack jets (Su-25s). They are now requesting more advanced fighters.

Western allies are split. The US and Germany have ruled this out, but previous red lines have not held for long. That the US Congress authorized $100mn for training Ukrainian pilots last year suggests this one may move too.

NATO operators of more advanced Soviet fighter jets which Ukraine already use (MiG-29s) have discussed sending these to Ukraine. Meanwhile, the Netherlands is considering transferring F-16s (a US multi-role fighter jet) to offset such deliveries. In theory, 34 MiG-29s (23 Polish and 11 Bulgarian; Slovakia is reportedly already preparing to send 11) could be sent, which would considerably strengthen Ukraine’s air combat capabilities.

Russian Escalation Remains a Risk

If it could, Ukraine would reclaim all occupied territories, including Russian-claimed Crimea. Advanced jets may provide them the means. However, such a move could provoke even stronger Russian action.

Ukraine and the more hawkish of the Western allies may assume such threats are overblown. There is some precedent for this. Last February, Russia announced any Western interference would mean war. In September, officials declared nuclear weapons could be used to defend territory it claimed in sham referendums. Neither threat came to anything.

However, Crimea is far more integrated into Russia than other claimed areas. It has been occupied since 2014 and hosts their Black Sea fleet. The bet that Putin’s red lines will keep shifting may be a dangerous one. Furthermore, if a Russian ground offensive stalls due to new weapons delivered to Ukraine, Russia may seek to target their supply.

Alternatively, Russia may seek to further disrupt energy supply. We were perhaps overly bearish on the situation at the end of last year, but it remains the case that the EU is highly exposed to energy prices, and Russia has the incentive and track record to hit them.

Little Sign of Serious EU/NATO Disunity

European countries still fear ‘escalation’. That is why Germany remains steadfastly against jet deliveries, even while French officials have played down the risk. So far, such divisions have delayed more than prevented Western support.

However, right now economic conditions are relatively rosy, and (after a warm winter) risks to energy supply are on the backburner. This may not always be the case.

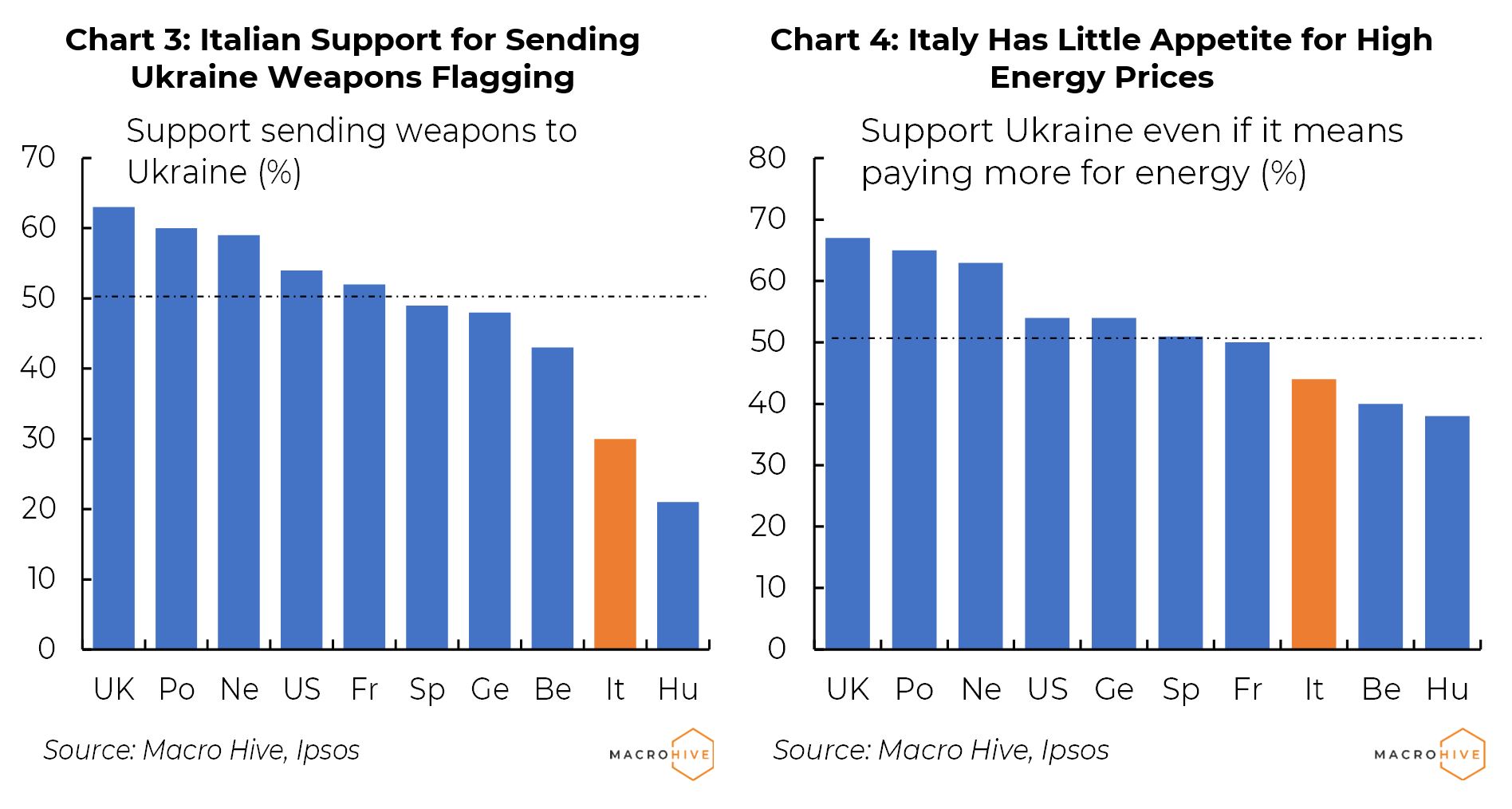

Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni has so far firmly supported Ukraine, but her coalition’s commitment is less strong. The Italian public strongly supports helping Ukraine, but support for sending weapons is relatively low, as is willingness to pay higher energy prices (Charts 3 and 4). The risk could be that if the country’s economic fortunes deteriorate, and if gas prices begin to rise again, appetite for support may wane.

The market may now be overly comfortable with the situation following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. The risk that new geopolitical crises emerge is almost certainly under-priced. Subsequent flashpoints are high risk, and such events may unfold very quickly. Global energy supply chains remain particularly exposed to such risk. Even issues that may seem very localized initially run the risk of growing and drawing in whole regions (as per the Arab Spring). We will keep a close eye on such issues and advise others to do similarly.

Spring sale - Prime Membership only £3 for 3 months! Get trade ideas and macro insights now

Your subscription has been successfully canceled.

Discount Applied - Your subscription has now updated with Coupon and from next payment Discount will be applied.