Monetary Policy & Inflation | US

Monetary Policy & Inflation | US

This article is only available to Macro Hive subscribers. Sign-up to receive world-class macro analysis with a daily curated newsletter, podcast, original content from award-winning researchers, cross market strategy, equity insights, trade ideas, crypto flow frameworks, academic paper summaries, explanation and analysis of market-moving events, community investor chat room, and more.

Hopes for a soft landing have ebbed and flowed since the Fed started its tightening campaign earlier this year. More recently, they have flowed again following several negative inflation and demand surprises plus the announcement of a Fed ‘pivot’.

Yet recent data and the macroeconomic fundamentals suggest these hopes are likely to be disappointed. Since the pandemic, core inflation has slowed twice, only to start accelerating again (Chart 1). Trimmed mean and median price have proven more reliable indicators of trend, as academic research had predicted. Nothing definitively signals they are falling.

Conversely, the Cleveland Fed inflation nowcast currently predicts the November Core Consumer Price Index (CPI) at 51bp MoM, up from 27bp in October. Predictions also show October and November Core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) at 28 and 41bp, respectively, from 45bp in September.

Concerning growth data, one of the best aggregators is the Atlanta Fed GDP nowcast. It is currently pricing Q4 GDP at 4.3% QoQ seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR) and rising. By contrast, the blue-chip forecast is less than 0.5%.

Nor has the big-picture macro story on inflation changed. On goods inflation, the deflation prevailing before the pandemic is unlikely to return. Reasons include geopolitical fragmentation, a mismanaged transition to green energy, and structural demand changes. (For more information, see Isabel Schnabel’s speech at Jackson Hole.)

For services inflation, labour is the main input, and wages are the main driver. Quality wage indicators such as the Atlanta Fed median wage or the Employment Cost Index have paused recently (Chart 2). However, real wages have been falling, which is inconsistent with the lowest unemployment rate in 50 years. A catch-up is likely, possibly in January, as wage negotiation typically happens at year-end.

But even at current levels, wage growth is inconsistent with 2% inflation. Wage growth needs to slow, which requires an increase in unemployment.

A feedback loop between inflation and wages, that is, the wage-price spiral, has already taken root (Chart 2). I think a US wage-price spiral is unsurprising as:

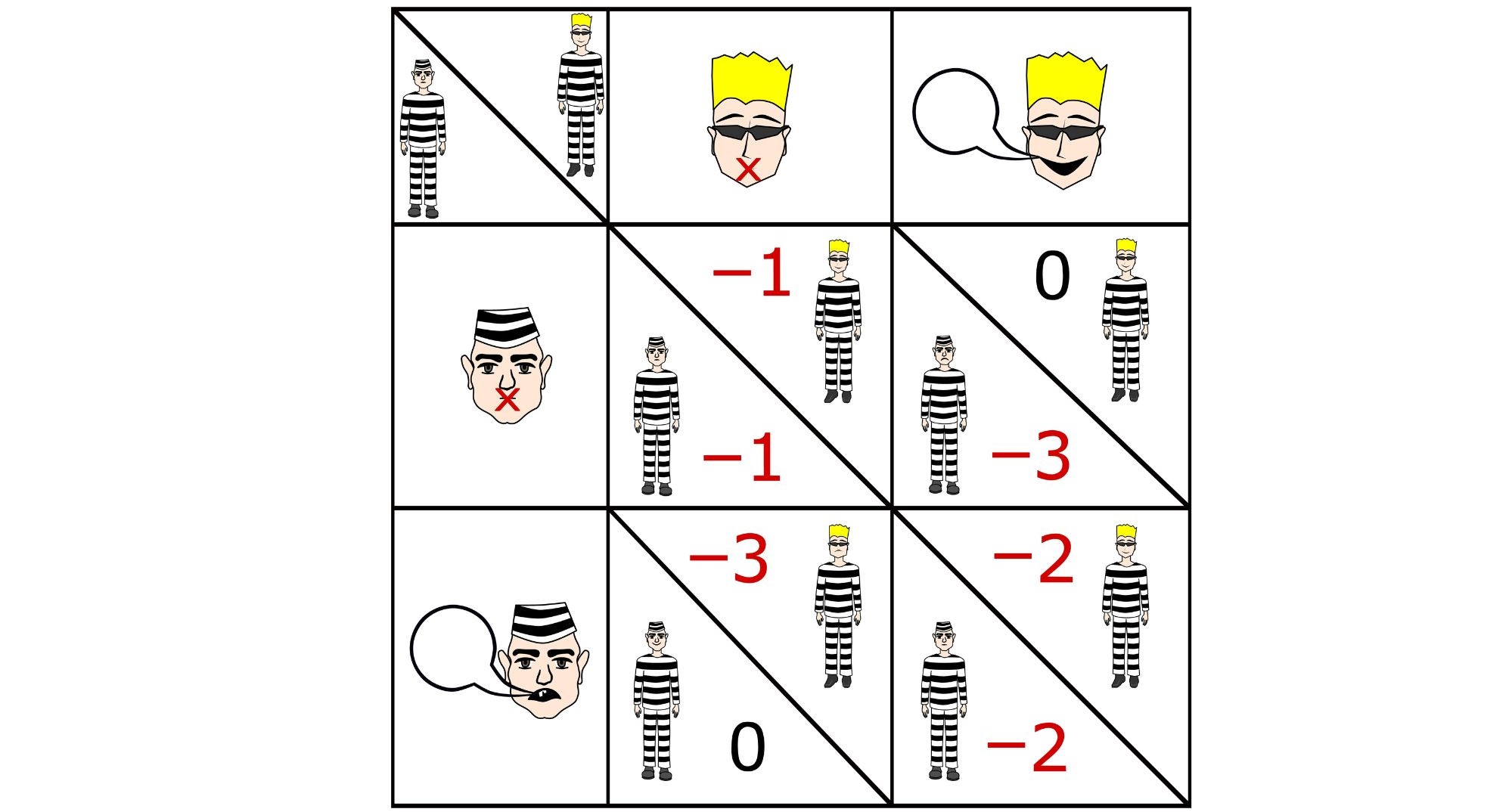

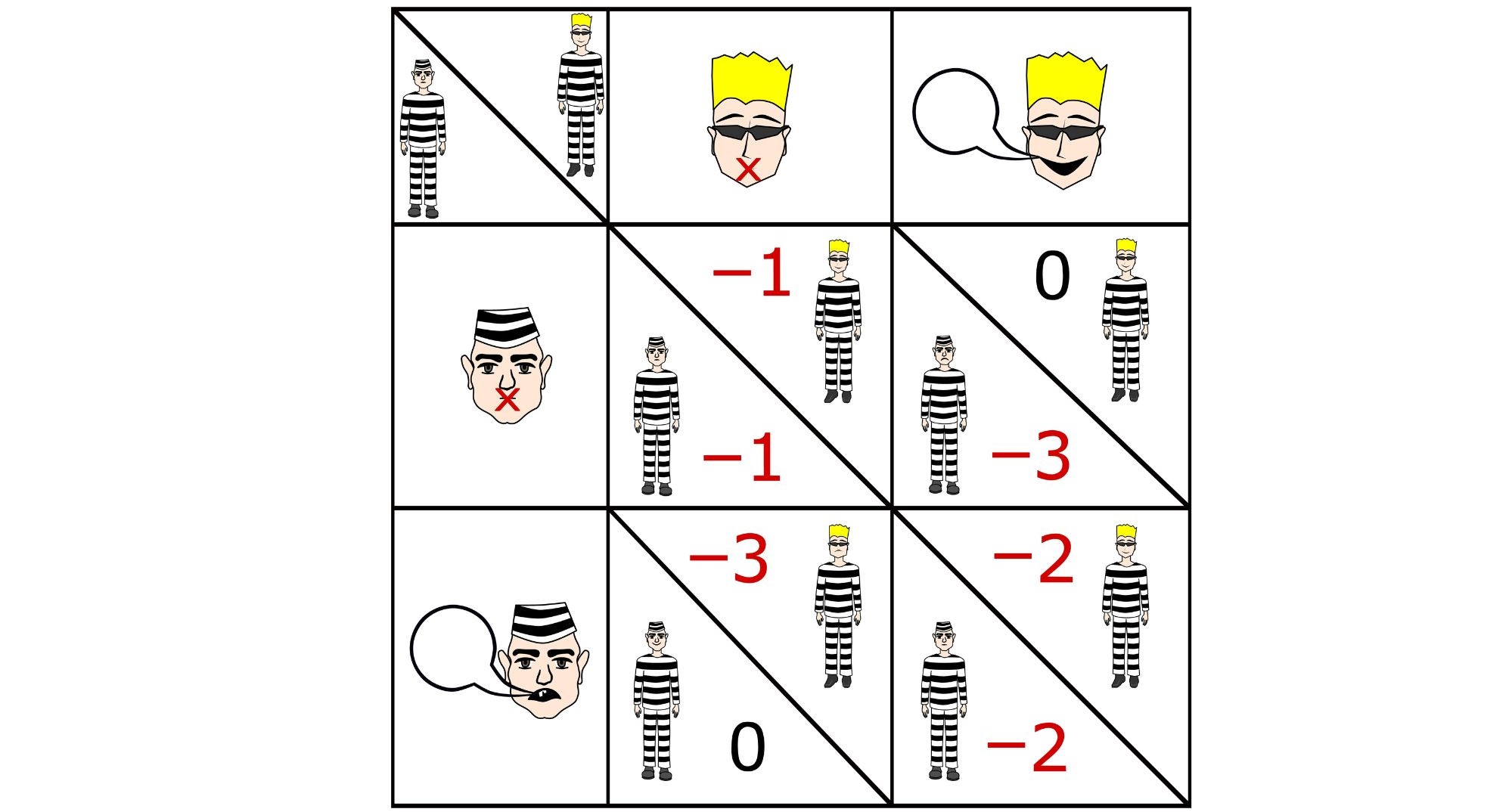

Problematically, the wage-price spiral is hard to break since workers and businesses are setting prices and wages independently. In that sense, inflation is like the prisoner’s dilemma (Table 1).

In the prisoner’s dilemma, two delinquents have been caught committing a crime but are interrogated separately. If they both deny the crime has been committed, they will walk free as the police have no other proof. However, if one delinquent confesses and the other does not, the latter will get a heavier sentence than if both confessed (Table 1). Therefore, both delinquents end up confessing. But they could have walked away, had they been able to communicate and agree not to confess.

The wage-price spiral and prisoner dilemma are similar. For instance, if workers and businesses could commit to not raising wages and prices above a certain level, they could obtain the same real wages and profit margins with lower inflation. Therefore, the central bank would not have to tighten policy and bring about a recession that would make both workers and businesses worse off.

In that sense, a recession can be seen as a substitute for formal coordination between workers and businesses. And the more credible the central bank, the shallower the recession can be. Ideally, with forward-looking workers and businesses, and a credible central bank, inflation would not happen since the threat of recession would deter them.

I think something similar was at work in the 1988–89 tightening cycle (Chart 4). Core CPI rose from 2.8% YoY in February 1987 to 4.6% in December 1988 and subsequently fell. In those days, the memory of the recession of 1980–82 was still fresh and likely helped moderate inflation.

This time, the Fed’s inability to react fast to inflation and two decades of ultra-loose policy may have weakened its credibility. Recent comments on the risks of overtightening from the more dovish Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) participants will likely weaken Fed credibility further. Unsurprisingly, many market participants have expressed doubts that the Fed will keep hiking once unemployment starts rising above U*.

In the 1970s, this coordination of wage and price setting was attempted through price controls. In 1971, the Nixon administration imposed a 30-day freeze on wages and prices. These did little to tame inflation, partly because monetary and fiscal policies were too loose. In the current political context, and with the US government’s weak implementation capacity (as demonstrated by the inefficient policy response to the pandemic), these would be unfeasible.

I struggle to find evidence that inflation is falling or that the data no longer supports my big-picture macro view.

Therefore, I continue to expect an 8% terminal federal funds rate (FFR), though I see the risk to the view as coming more from the Fed than the economy. With unemployment still very low, the Fed has faced little political pressure.

Once unemployment starts rising and the US economy experiences pain, possibly year-end 2023, the Fed will face much stronger pressure. I expect the Fed to resist that pressure, but it may not. If it does not, the experience of the 1970s suggests deeper inflation pressures, stronger policy tightening, and a more painful recession.

Spring sale - Prime Membership only £3 for 3 months! Get trade ideas and macro insights now

Your subscription has been successfully canceled.

Discount Applied - Your subscription has now updated with Coupon and from next payment Discount will be applied.