Summary

- A new BIS working paper explains how trends in capital flows have changed since the GFC.

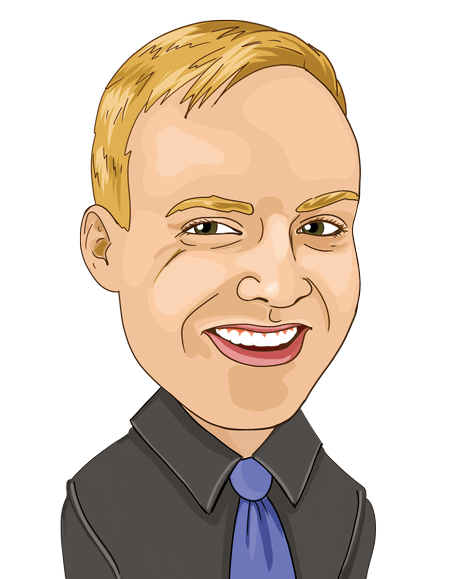

- It highlights a decline in cross-border bank lending and a rise in market-based financing.

- Alongside an increase in EME participants, a more diversified investor base should improve financial stability.

Introduction

The Covid-19 crisis triggered a sharp reversal of capital flows to Emerging Market Economies (EMEs). Also known as a sudden stop, this withdrawal of foreign funds can significantly damage economies. However, healthier growth prospects, unconventional monetary policy, expansionary fiscal policy, and large reserve buffers helped EMEs navigate the pandemic better than during previous sudden stops. A new BIS working paper suggests changing capital flow trends over the last decade may also have helped. In particular, the authors find:

- The rise of EME investors and the growth of local currency bond markets have helped to diversify EMEs’ investor base.

- EME banks have increased cross-border lending, and the share of EMEs’ liability represented by portfolio debt has risen steadily since 2008.

- The frequency of bank-related capital flow surges into EMEs has fallen, and gross inflows into Advanced Economies (AEs) are now more volatile than to EMEs.

Five Trends in Capital Flows Since the GFC

Previously, net capital flows were used to gauge the impact of net borrowing from the rest of the world on a country’s real economy, asset prices and exchange rates. However, recent literature has suggested net positions may be an unreliable indicator of financial vulnerabilities. They could also mask maturity mismatches, and they take no account of differences in the behaviour of domestic and foreign investors. To overcome such issues, the authors use gross capital flows.

The authors observe that since 2009 gross capital flows never regained their pre-GFC upward momentum. Bank loans, which are considered ‘other’ investment flows, portfolio debt and equity flows have all been lower during 2009-2019. This is particularly the case for inflows into advanced economies (AEs). By contrast, inflows into EMEs have held up relatively well. Emerging Asia in particular has seen inflows double as a percentage of global GDP since 2009.

Capital flows comprise various subcomponents (see Figure 3 of ‘High-Frequency Capital Flow Proxies Are Good at Predicting BoP Flows’). One of the most significant changes to capital flows in recent years has been the declining role of banks. Cross-border bank lending has dropped noticeably, especially for borrowers in AEs, and this has been offset by the growing role of asset managers, investment funds and other non-bank financial intermediaries. The rise in portfolio debt has been particularly noticeable for EMEs (Chart 1).

Another post-GFC change has been the increasing presence of the public sector in international financial markets in both borrower and investor roles. An estimated 38% of total capital inflows to EMEs and more than half of portfolio inflows are attributable to the public sector. According to the authors, ‘the rise of public sector borrowers and investors is creating ever closer links between public sector entities within countries and across borders’. For example, public sector entities hold more than half of US Treasuries.

A third notable change has been in the ‘financialisation’ of FDI. By financialisation, the authors mean the ‘phantom’ FDI associated with the complex financial and tax strategies that firms implement to reduce costs. Shifting intellectual property rights, relocating headquarters, channelling funds through offshore subsidiaries, and using cross-border intra-company loans have changed the definition of traditional FDI. The FDI component is now less of a reflection of real investment or the expansion of production technologies.

Increasing regional integration among EMEs has also stood out. In Asia, the domestic investor base has expanded, contributing to higher intra-regional cross-border holdings of debt securities – the share of EME-issued debt securities held by other EMEs rose from 4% in 2006 to 14% in 2019. Also, EME banks have made inroads into global cross-border lending. Chinese banks now account for 26% of all cross-border claims on emerging Asia.

The fifth, and last significant trend since the GFC, has been the continuing US dollar dominance in international finance. Despite efforts by EMEs to develop local currency government bond markets, improve macroeconomic policies and increase the resilience of domestic financial systems, EME corporates’ foreign currency debt has almost tripled since 2005 to more than $2 trillion (more than 16% of GDP). Foreign investor participation in EMEs increased from 14% to 29% between 2010 and 2014, but has since dropped back to 19% in the early 2020s.

Capital Flow Volatility, Sudden Stops and Covid-19

Central banks surveyed for the BIS paper identified higher capital flow volatility as a key post-GFC trend. On average, the authors find that gross inflows to AEs have been more volatile than gross inflows to EMEs. In particular, the volatility of bank lending, portfolio debt and FDI flows to AEs has increased. FDI flows to EMEs have also become more volatile, but bank lending and portfolio debt volatility has declined.

Despite the rise in capital flow volatility post-GFC, on average there have been fewer surges in gross capital flows (large increases relative to a reference level) in the last decade. This is especially the case for bank-related surges, although large portfolio debt inflows to EMEs have become more frequent since 2016. Meanwhile, the frequency of sudden stops (very low capital inflows) is unchanged, and they are more likely to occur in EMEs.

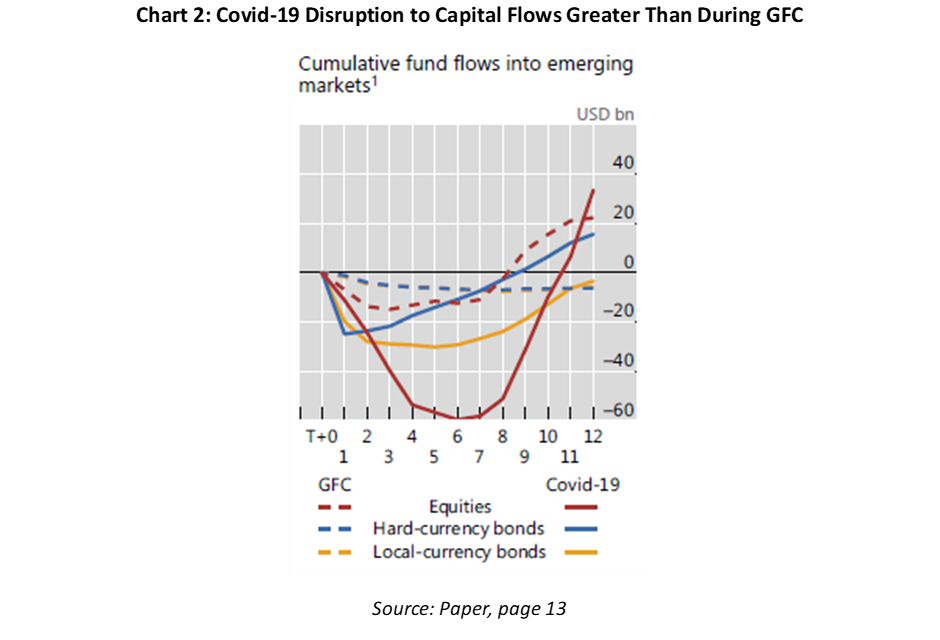

The Covid-19 pandemic triggered a sharp reversal of capital flows to EMEs and some AEs in March 2020. Inflows to EMEs recovered from April 2020, but only to countries with fewer economic vulnerabilities, robust policy frameworks and the pandemic under control. Also, the recovery was faster in equity inflows and into hard currency instruments (Chart 2). Moving forward, central banks regard the monetary and fiscal policy stance of an EME to be the largest factor in an investors’ near-term capital flow decisions.

Bottom Line

Capital flows feed into exchange rate and asset price determination. And so, changes over the last decade are important for investors. The BIS research highlights a fundamental shift in the drivers of capital flows, from bank-based to market-based finance. Meanwhile, EMEs have developed local currency bond markets and experienced a rise in EME investors, which have culminated in greater regional integration. This more diversified investor base should improve the resilience of such economies. However, the Covid-19 crisis is a reminder that portfolio investors and other non-bank financial intermediaries can still have destabilising impacts.

Citation

García López, G., Stracca, L., (2021), Changing patterns of capital flows, BIS, Working Paper (66), https://www.bis.org/publ/cgfs66.htm

Sam van de Schootbrugge is a macro research economist taking a one year industrial break from his Ph.D. in Economics. He has 2 years of experience working in government and has an MPhil degree in Economic Research from the University of Cambridge. His research expertise are in international finance, macroeconomics and fiscal policy.

(The commentary contained in the above article does not constitute an offer or a solicitation, or a recommendation to implement or liquidate an investment or to carry out any other transaction. It should not be used as a basis for any investment decision or other decision. Any investment decision should be based on appropriate professional advice specific to your needs.)