Economics & Growth | Monetary Policy & Inflation | US

Economics & Growth | Monetary Policy & Inflation | US

Biden administration and Republican negotiators have repeatedly warned that crossing the X-date, the first day when the Treasury does not have enough cash to cover all its bills, would lead to a US default.

This is very misleading. For the US to default, it would need to be late in paying the interest and principal falling due on its debt. In addition, a holder of defaulted Treasury securities would have to ask the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA)’s Determination Committee to declare a credit event.

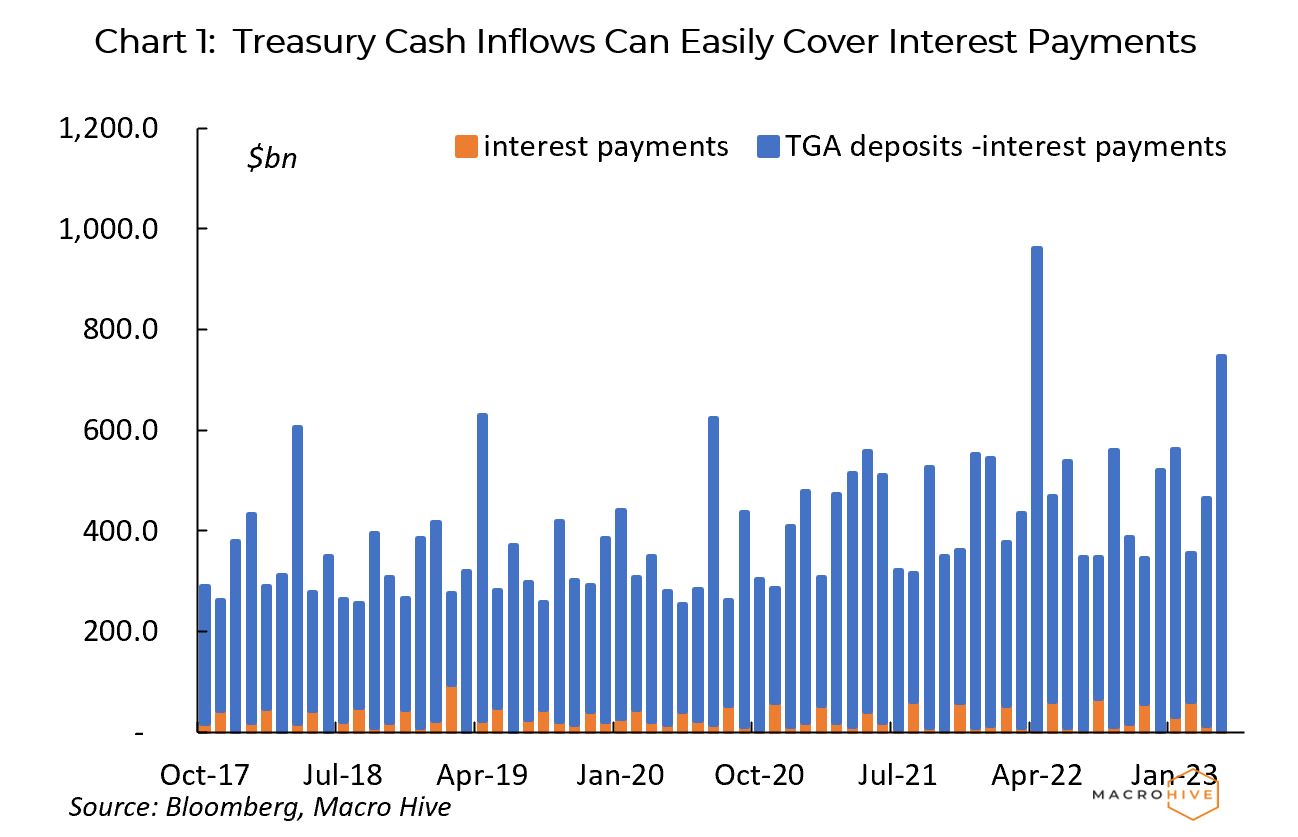

In reality, the US has more than enough inflows of cash to over its interest payments (Chart 1). And as long as it can roll over its principal, it will remain current on its debt service.

In this note, I review the contingency measures the Treasury and Fed have likely already readied to ensure that debt service remains current after the X-date. Past administrations have denied that such contingencies exist as part of a debt ceiling negotiating strategy that exaggerates the – very real –risks of hitting the X-date. But the information is available from past Fed transcripts and Congressional Republican inquiries.

The transcript of the FOMC conference call of 16 October, 2013 makes it very clear. Once the X-date had been hit, the Treasury was going to prioritize interest rate payments.

The Treasury hit the debt ceiling on 31 December, 2012. Protracted negotiations ensued. On 4 February, the debt ceiling was suspended until 18 May 2013. On 1 October, the government went into partial shutdown and on 16 October, the day of the FOMC conference call and a day before the Treasury-determined X-date, the debt ceiling was suspended until February 2014.

The transcript reveals that, had the X-date been hit, the Treasury’s handling of government payments was to be based on three principles:

Furthermore, inquiries by Congressional Republicans revealed that in 2011 and 2013 the Treasury and Fed ran extensive ‘tabletop’ payments prioritization simulations. The inquiries revealed that, in addition to debt service, the Obama Administration considered prioritizing Social Security and veterans payments.

In the call transcript the New York Fed’s head of markets explained that after the X-date was hit, the biggest risk to financial stability was a loss of market access by the Treasury, in practice a failed auction.

The Fed’s market stabilization plans were therefore focused on preventing this. They comprised of three categories:

Any Treasury security with delayed principal or interest payment would be accepted in these operations, but at market value. The Fed felt that this principle was allowing it to provide operational support to the Treasury market without taking on default risk and compromising its independence from the Treasury.

The FOMC further discussed at what stage to announce the establishment of the facilities. The Fed did not want to announce its measures too early and seem to underwrite political dysfunction. On the other hand, it wanted to announce early enough to prevent a failed auction and to reduce uncertainty around the valuation of Treasury collateral.

Ultimately, the Fed communications strategy was not tested since the standoff was resolved on the day of the FOMC call. The minutes of the October 2013 meeting, published on 20 November listed the first category of measures and hinted that more were available depending ‘on the actual conditions observed in financial markets.’

Do Not Fight the Fed

A key difference between the current debt standoff and that of 2013 is that this time around the Fed is running quantitative tightening (QT), by contrast with QE in 2013. This makes for a backdrop that is less supportive of the Treasury market.

At the same time, the Fed’s unprecedented market support during the pandemic has created a precedent for comprehensive Fed underwriting of market functioning. It suggests to me that the Fed is likely to use every possible lever to support the Treasury market.

For instance, should the Treasury market experience strains, I would expect the Fed to pause QT and possibly engage in large scale Treasury purchases. The Fed would see a breakdown of the Treasury market as threatening financial stability and the attainment of its inflation and employment mandate.

In addition, while the October 2013 call does not mention support to Money Market Funds (MMFs), during the pandemic the Fed established a facility to provide liquidity to MMFs. It is likely that the facility would be revived in the event of X-date associated MMF strains.

I would also expect the Fed to announce its support measures early (i.e., after the Treasury has announced payments prioritization), but well ahead of Treasury auctions.

While the Fed would bring to bear the full strength of its printing presses and its $5.2tn in Treasury securities holdings, these measures do not completely remove the market risks associated with hitting the X-date.

For instance, should primary dealers decide they do not want to participate in auctions, there is little the Fed could do to avoid a failed auction. That said, Treasury announcement of payments prioritization together with the facilities the Fed is likely to put in place—and some ‘moral suasion’ —would greatly reduce the incentives for a dealers’ strike. Basically, the Fed would guarantee the purchase of any failed security.

And the success of the Fed operations would be contingent on the Treasury’s willingness to prioritize payments. Without payment prioritization, default would be likely and could trigger an unprecedented market collapse.

So far, the market reaction has been limited. T-Bills maturing in early June have seen their yields rise to 7%, against 5.1% for OIS. There has been a limited negative impact on stocks and no discernable impact on the yield curve or on gold.

Fitch ratings announced on 14 May that it was placing the US AAA rating on negative watch, but this did not elicit much market reaction. A previous downgrade of the US by S&P in 2011 did not have much market impact either.

As X-date approaches, a larger market selloff is likely. However, the contingency measures discussed above could make a build-up of US arrears on non-debt service payments sustainable. In effect, the debt ceiling standoff would turn into a form of government shutdown.

In turn, this could place a floor under the markets and weaken the incentives for the parties to find a compromise.

But even government shutdowns eventually get resolved, though the last one in 2018-19 lasted 35 days.

Spring sale - Prime Membership only £3 for 3 months! Get trade ideas and macro insights now

Your subscription has been successfully canceled.

Discount Applied - Your subscription has now updated with Coupon and from next payment Discount will be applied.