Asia | Monetary Policy & Inflation

Asia | Monetary Policy & Inflation

Japan has been contending with deflation and implementing quantitative easing (QE) since the 1990s, well before other advanced economies. In 2022, it could also start pioneering reliance on ‘people’s QE’ – issuing reserves to the public, rather than the banking system. How would this happen?

Japanese inflation has benefitted little from the pandemic. In December 2020, it fell to -1% and has since recovered to barely above zero. Japan’s recovery also lags the rest of the world: its GDP has been falling since Q4 2020, and unemployment remains stuck at a six-year high.

In response, incoming Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has announced fiscal measures worth $490bn (10% of GDP). But this seems unlikely to be more effective than the previous three. Frustrated, he may decide the time has come for more radical policies, namely the people’s QE.

The people’s QE works like traditional QE. The central bank buys bonds and creates reserves. But instead of buying them from the private sector, it buys them from the Treasury. The Treasury then credits the proceeds to citizens’ accounts. The Bank of Japan (BoJ) could set up citizen accounts by issuing a CBDC, which it is currently developing.

The key difference between traditional and people’s QE would be who owns the reserves created by the BoJ. In traditional QE, banks largely own the reserves, and creating reserves only impacts the real economy to the extent that they support additional bank lending.

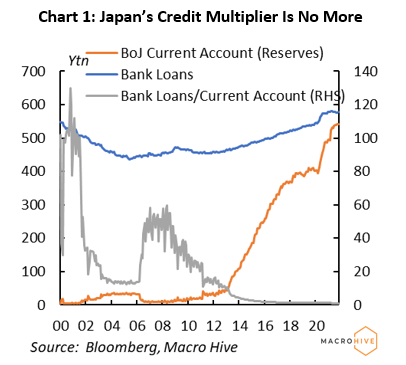

In reality, that has not happened. Since 2008, BoJ reserves have increased by Y550tn. But bank lending has increased by only Y130tn, and the credit multiplier has collapsed. As in other developed economies, Japan’s QE has supported economic financialization rather than the real economy: while Japan has been in recession since Q1, the Nikkei is up 8.5% since 1 January!

Under the people’s QE, by contrast, Japanese households would own the additional BoJ-issued reserves. Since the BoJ is part of the government sector, the people’s QE would effectively comprise cash transfers to households funded by the BoJ creating money. This could be a very powerful tool: in the US, a series of untargeted government payments to households, partly funded through QE, have brought inflation to a 30-year high!

Nevertheless, the people’s QE concept is gaining respectability. In 2015, then UK Leader of the Opposition Jeremy Corbyn suggested the Bank of England create money to fund public investment. In 2019, a UK economist wrote a book advocating it. In 2020, former Fed economists Julia Coronado and Simon Potter argued for it as an automatic stabilizer.

The people’s QE is powerful, difficult to calibrate and could well return inflation to Japan, and instability. Inflation returning would likely disrupt markets and the economy considerably as Japan’s institutions are now fully adapted to deflation. The people’s QE would likely be negative for currency and bonds, and perhaps even equities, depending on the magnitude and volatility of inflation and real growth shocks. It could also inspire other global central banks to copy the BoJ, which would be positive for gold and cryptocurrencies.

Spring sale - Prime Membership only £3 for 3 months! Get trade ideas and macro insights now

Your subscription has been successfully canceled.

Discount Applied - Your subscription has now updated with Coupon and from next payment Discount will be applied.