Monetary Policy & Inflation | US

Monetary Policy & Inflation | US

My main takeaway from Chair Jerome Powell’s testimony to Congress yesterday is that the Fed will respond to stronger inflation and data prints.

I came into the testimony expecting that a 50bp increase in the March SEP terminal FFR was a done deal but much less sure about a 50bp hike at the March meeting. On economic grounds alone, I think a 50bp hike is totally justified. I think decelerating the hikes was yet another policy mistake from the Fed.

But it is the Fed, not I, who sets the policy rate, and it has been consistently more dovish than I. So, I was unsure of two things. First, how does the Fed perceive the inflation problem? Second, how much control does Powell have over the FOMC, which is less hawkish than him.

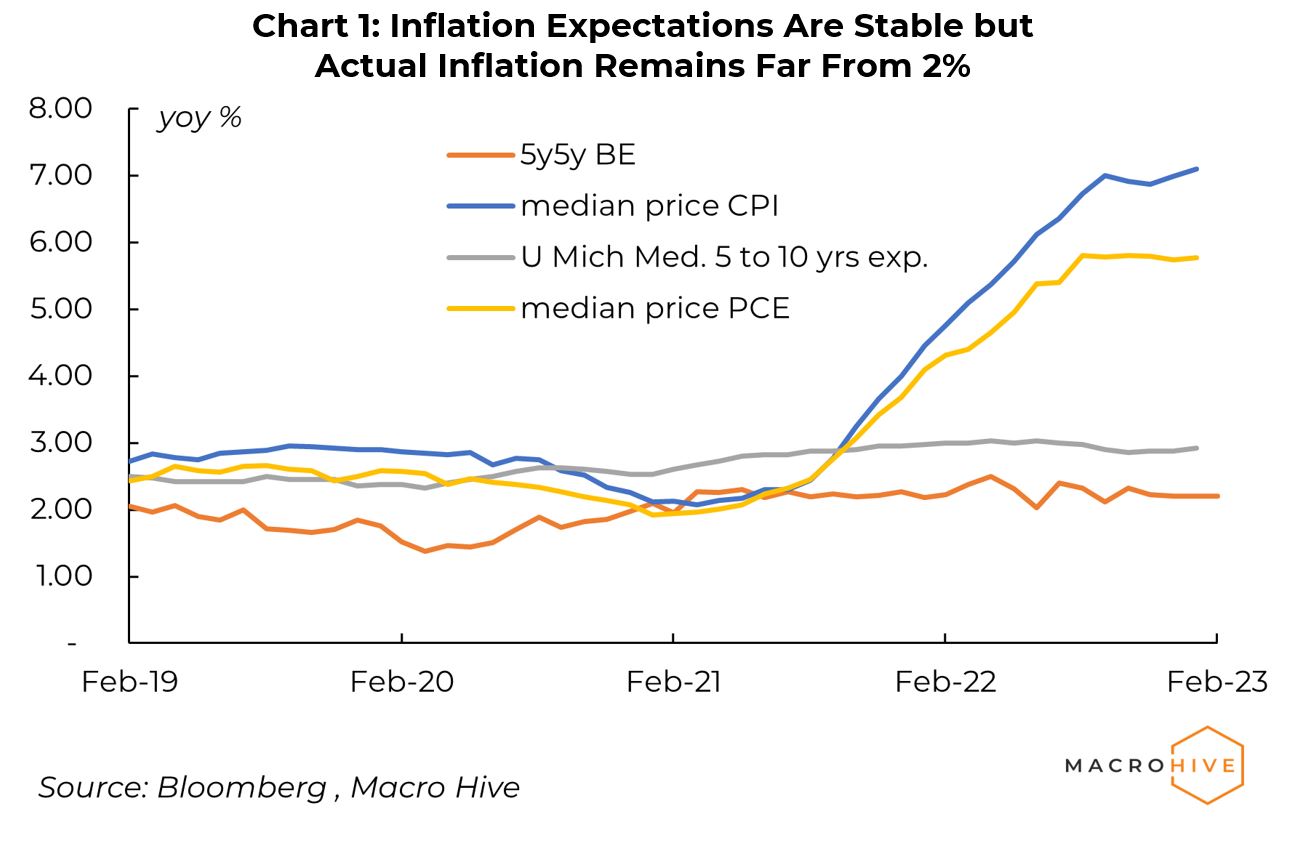

The Fed’s strategy of reacting to inflation prints is a recipe for remaining behind the curve since inflation lags indicators such as labour market tightness or demand strength. That strategy reflects that the Fed’s own inflation model, the expectations-augmented Phillips curve, predicted that the high inflation prints of 2021 would be temporary. After data falsified that model, Powell gave up on it and has not replaced it with another model.

Yesterday’s testimony shows that he will react not only to stronger inflation prints but also strong labour market and demand prints.

The FOMC hawks and doves have been looking at the same dataset but drawing very different conclusions. I think the doves are ignoring the signs of inflation pressures.

Powell would not have made yesterday’s strong statements if he was not confident that he could bring the FOMC to his views. This implies the doves are not totally oblivious to the data and, when confronted by their Chair, they will rally to a more hawkish stance.

I think 50bp in March is likely if, for instance, nonfarm payrolls are above 250,000 with signs of labour market tightness (e.g., no increase in participation, faster wage growth) and/or CPI is above 40bp for core MoM. As always, these are more examples than mechanical triggers for a 50bp hike. The Fed looks at economic news holistically: it tries to form a broad picture of the economy. In any event, I will update you in real time on how the data is likely to impact the Fed.

Longer run, the market is pricing peak FFR at 5.64 in September 2023 and cuts after that. For instance, 1y1y OIS is 4.61%. Short of a catastrophe (e.g., open conflict between Russia and the US), I could not disagree more. The last time core PCE was 4.7% was in February 1989. It took six years for core PCE to fall to 2%, compared with the three years indicated in the Fed’s December SEP. This time, disinflation will take longer and be more painful because the Fed has much less credibility than in the 1980s.

Spring sale - Prime Membership only £3 for 3 months! Get trade ideas and macro insights now

Your subscription has been successfully canceled.

Discount Applied - Your subscription has now updated with Coupon and from next payment Discount will be applied.