Economics & Growth | Emerging Markets | LATAM | Monetary Policy & Inflation | US

Economics & Growth | Emerging Markets | LATAM | Monetary Policy & Inflation | US

Analysts and investors are comparing the current banking stress initiated by the run on Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) to the 2008-9 financial crisis – as they did when the COVID-19 pandemic began. As then, I do not think the analogy fits at all.

The similarities are a rash of bank stress and failures, but this time in regional banks – shades of the thrift crisis of the 1980s – and not large money centre banks. Moreover, the problem does not stem from the nonpayment of long-term loans, e.g., mortgages, or overly leveraged derivatives. It stems from duration losses on mainly long-dated US Treasury bonds due to increases in interest rates promulgated by the US Federal Reserve to fight inflation.

In an interview in the WSJ, former FRB Kansas City President Thomas Hoenig focuses on the problems with giving US Treasuries a zero-risk rating. That is, banks do not have to hold reserves against US Treasuries as they are considered riskless. But that only means default risk was low, not market risk. When interest rates rise, bond prices fall, and this is the crux of the losses at these banks.

That the US Treasury and Fed have guaranteed all sizes of bank deposits at these regional banks will have deleterious effects in the longer term by increasing moral hazard and the returns to “too-big-to-fail.” Many observers have adequately discussed these problems.

Here, however, we focus more on the structural issue: the United States is moving toward fiscal dominance. Banks and investors in fixed-income assets, whether bonds, loans, or derivatives, are subject to market or duration risk as they hold longer-term assets against short-term liabilities. In the case of bonds, we mainly look at duration.

Duration is a measure of an asset’s maturity, in this case bonds. But it also measures the sensitivity of the price of a bond: the percentage change in the price of a bond due to a 100 basis-point change in the market interest rate for that bond. The sign is negative because prices of bonds that carry a given coupon rate must decline if market interest rates rise. And the longer the maturity of the bond, the larger the duration.

Currently, the duration of a newly issued 10-year US Treasury bond at the end of February was around 8.11 years. That means that if the rate on the 10-year rises by 100bps, the price of the bond will decline by 8.11%. The duration on a 5-year Treasury was around 4.4 years and on 2-year Treasuries was 1.8 years at the end of February.

Obviously, the duration of the banks’ US Treasury portfolios was some weighted average of these durations, not to mention their mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and loan portfolios. However, banks must mark to market their bond holdings and only worry about provisioning on loans if there is delinquency.

The interest rate increases since January 2021 are significant. The 10-year rose around 287bps; the 5-year rose 332bps, and the 2-year rose 431bps as of February. Multiplying each of these by the respective duration leaves losses on 10-year at 23.3%, 5-year at 15.1%, and 2-year at 15.1%.

These are large losses for any investor but especially for banks. Because these losses are not realized if the bank or investor does not sell the bond, they can recover their whole investment plus interest by holding the bond to maturity. The banks had put these longer duration bonds in the hold to maturity portfolio for those reasons. Still, depositors became nervous and withdrew deposits at a head-spinning rate.

With short-term liabilities and longer-maturity assets, banks always have a duration mismatch and thus liquidity management has proven as important as non-performance on loans. But the current errors in liquidity management stem from large errors not only in expectations about inflation but also about how the US Fed would react (see Welcome to Inflation, Parts 1 and 2). That is, the market has erred not only on the ‘transitory’ nature of the current inflationary process but on the much-improved monetary policy stance of the US Fed.

The late but welcomed tightening of Fed policy and hawkish rhetoric have belied the roughly five false starts the market expected for the Fed to stop tightening. And the progressive interest rate increases and interest rate volatility because of these errors has caused duration losses to anyone owning US Treasury bonds and bills.

Clearly, the current banking problems do not arise from borrower risk but from market risk. The US government has issued USD10 trillion in debt between 2016 and 2022, of which USD7.5 trillion has been issued since 2020. Now, the US government depends increasingly on banks to finance its deficits and roll over its debt.

Consequently, banks wield increasing power to force the Fed to ease policy – the definition of fiscal dominance. That the Fed continued to raise the Fed Funds and signalled continued rate increases at the 22 March 2023 meeting are good signs. However, that it lowered the pace of increases following these financial difficulties is discouraging.

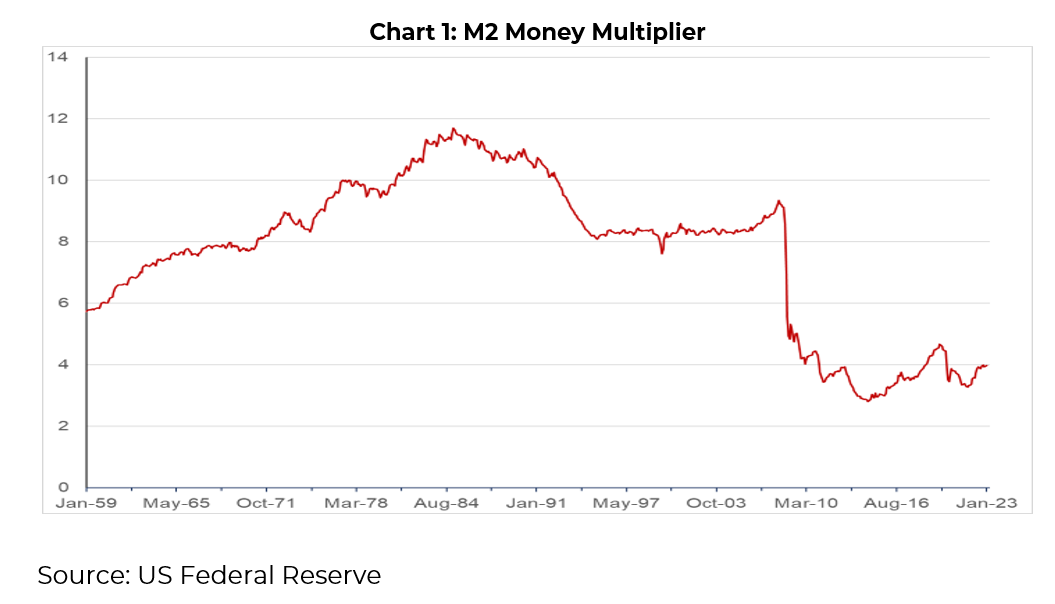

I do not think so. Not only is this not a default problem as in 2008, but the leverage in the system is much lower (Chart 1). All the deleveraging that occurred after the 2008 crisis as measured by the M2 money multiplier – the ratio of credit created by the banking system (inside money) to the monetary base (outside money) – remains at low levels. Because leverage is low, and capitalization is high, this current financial disturbance seems highly containable, as opposed to 2008. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell pointed this out after the 21 March 2023 FOMC meeting.

The upshot is that the more government debt the banking system must fund, the more power the system has to force changes in monetary policy to the sacrifice of lower inflation. When a government issues huge amounts of debt to the financial system, mainly to banks, any attempt to tighten monetary policy causes a loss to the banking system on its existing debt portfolio, either because of price declines, or because their liabilities will see an immediate increase in remuneration. Banks, if they can, push to force the central bank to loosen monetary policy by lowering rates and buying government debt, fuelling inflation that the central bank at first tried to combat.

This regime is one that suffers from fiscal dominance. And as Aloísio Araujo demonstrated in a presentation on 21 March 2023, the dynamics moving toward fiscal dominance are only reversed by fiscal austerity.[1] Persistently large deficits will cause a country to gradually move toward this regime where the banks can dictate monetary policy by holding the government hostage in finance government debt.

Most countries that have had fiscal issues suffer from some affect of fiscal dominance. Bill Gruben and I showed that countries with fiscal dominance not only tend to have higher inflation and interest rates but also that fiscal austerity is expansionary in Latin America, contrary to the usual Keynesian conclusion.[2]

The Brazilian government bond market is large and liquid, mainly due to reforms taken in the late 1960s, especially the implementation of inflation-linking. Even with low levels of duration, banks have backed the central bank on numerous occasions.

Starting in the late 1970s and exacerbated by the Latin American Debt Crisis of the 1980s, Brazil tried to deal with inflation by tightening monetary policy without fiscal austerity. It never worked as banks on numerous occasions threatened to boycott government bond auditions if the central bank did not ease, despite the short duration of government bonds, fixed-rate or index-linked. Moreover, since then, in the face of bank stress and the banks’ want to reduce duration, the Banco Central will undertake massive auctions, buying longer term paper and selling shorter term paper. This occurred many times over the last 40 years; the last large intervention occurred during the 2008-9 crisis.

One example is 1985, when the central bank had tried to control inflation with tighter monetary policy but without fiscal adjustment. In the event, the Banco Central president was dismissed, and the government embarked on several failed attempts at inflation stabilization using price controls (Plano Cruzado, Cruzado Novo, etc.). The environment was always one of continued fiscal deficits and accelerating inflation, exactly as Araujo et al. (2022) predict.

Brazil was only able to rid itself of the shackles of fiscal dominance when it finally undertook fiscal adjustment starting at the end of 1998 under an IMF agreement and floating the exchange rate in 1999. Unfortunately, Brazil is on the path toward fiscal fragility again and perhaps fiscal dominance if the current government’s plans carry through.

In 1984, 12.9% of bank credit was held by Brazil’s banks in government bonds. That ratio is now close to 40% as Brazilian banks are the main market-makers in government bonds as well.

Meanwhile, US banks’ holdings by US Treasury securities rose the end of 2019 from 16% to 19% of the total outstanding stock of bonds held by the public. They are the main intermediaries in selling bonds to the general public and are committed to making markets in US Treasuries as dealers. If we add in MBS, banks hold a whopping 50% of these fixed income securities, giving them extraordinary power over the Fed.

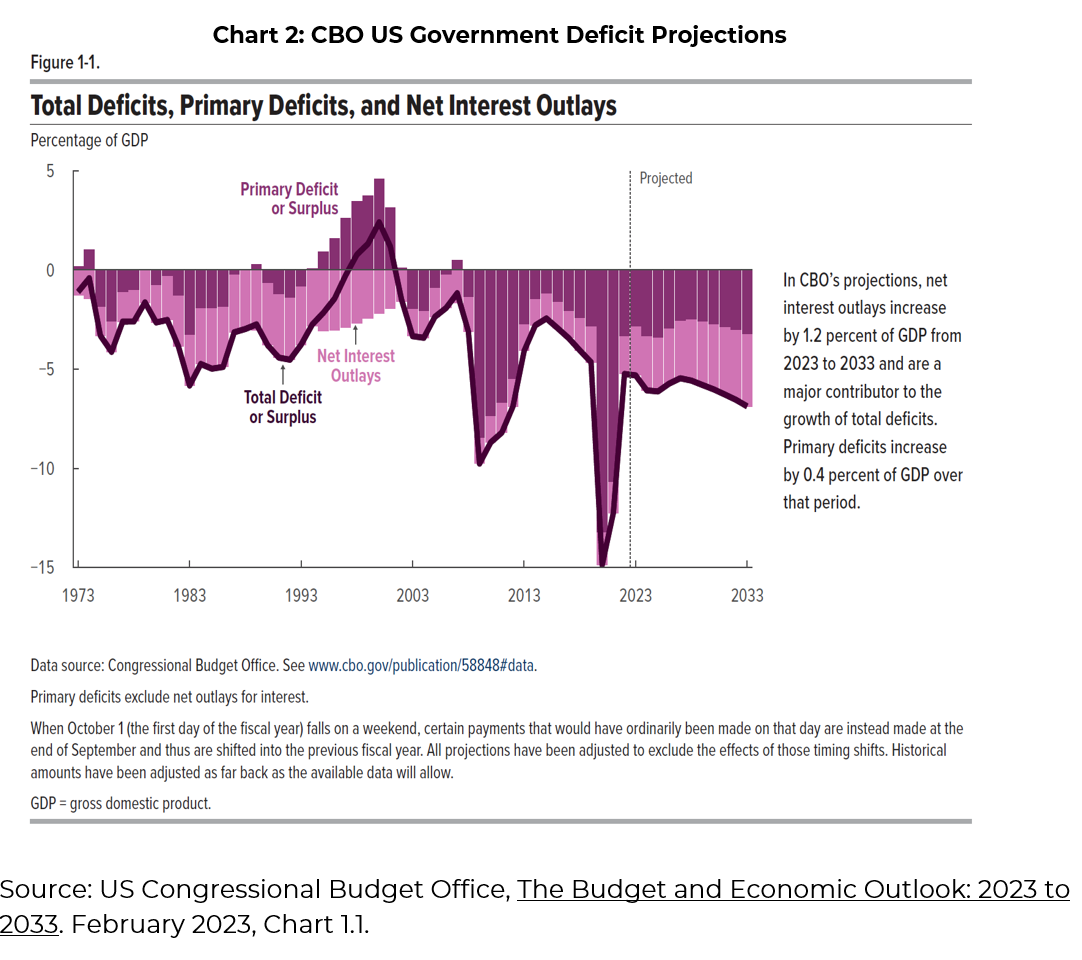

The administration was expecting primary fiscal deficits out into the indefinite future. The only way this is sustainable is for the real rate of return on government bonds to remain below real economic growth indefinitely. That is not possible except through continuously accelerating inflation. I checked whether the CBO’s forecasts had changed. The deficit projections have worsened (Chart 2). I copied and pasted the graph directly from the CBO projection spreadsheet. The US Treasury is expecting the US government to become – or perhaps it already has – fiscally fragile and continue into fiscal dominance, where banks can subvert any Fed attempt to fight inflation because of the need to finance itself.

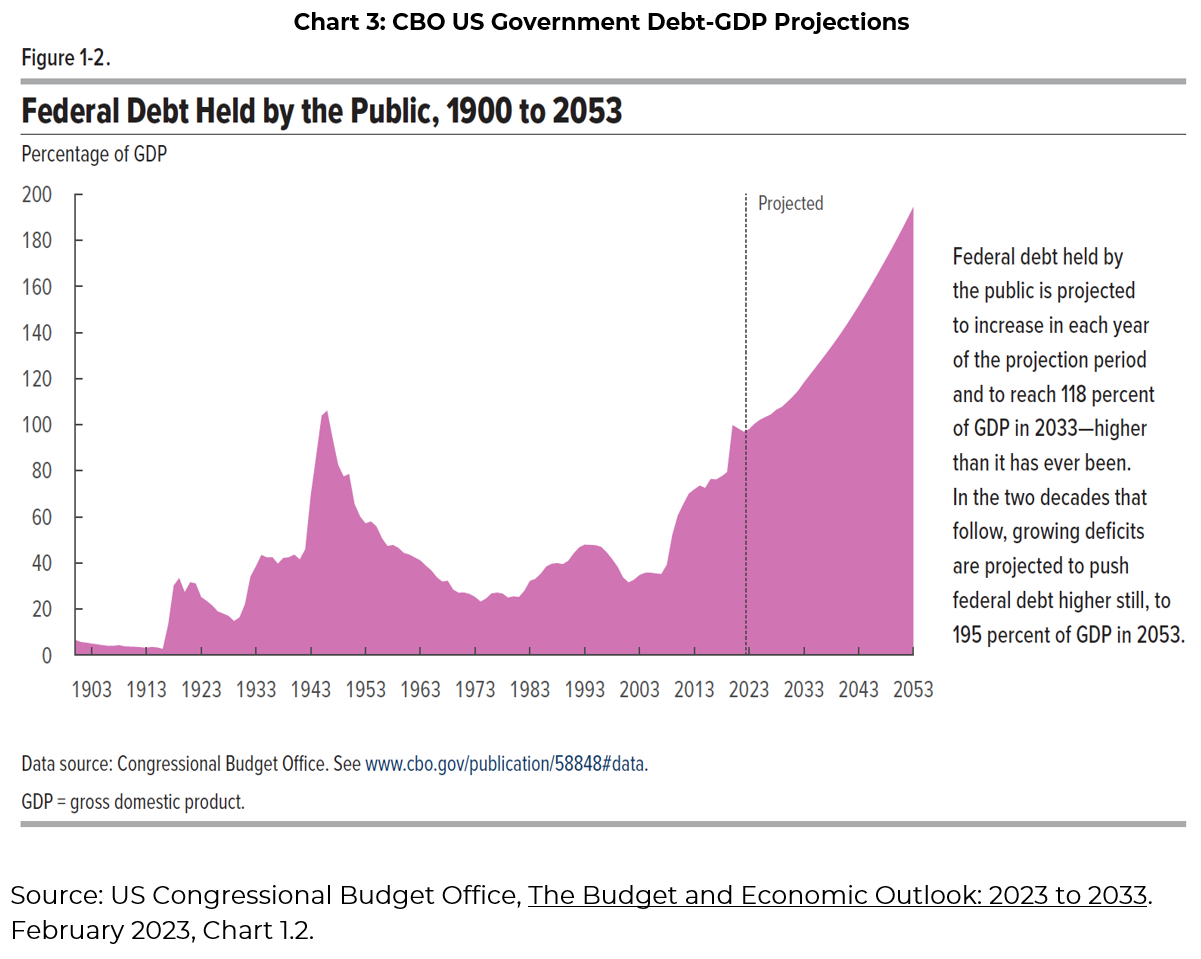

The CBO’s projections for the government debt-GDP ratio reflect this as well, with the ratio exploding to almost 200% of GDP (Chart 3). Of course, these projections are impossible as either inflation will accelerate, or a future government will react by imposing a likely painful fiscal adjustment. The CBO assumes inflation will fall to 1.3% in 2033 from 2022’s 5.7%. Inflation is more likely to explode than the debt-GDP as fiscal dominance erodes the credibility of both the US Fed and US Treasury.

The Fed has taken on a much-improved austere stance since we last wrote on the subject. It is now tighter, leading many to argue that lagged effects will take time to reduce inflation.

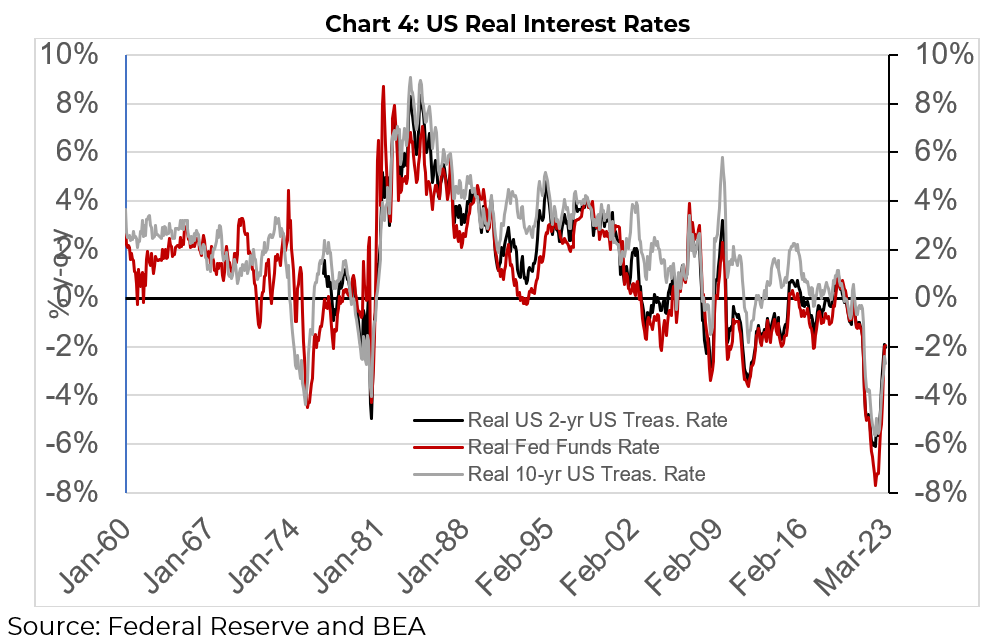

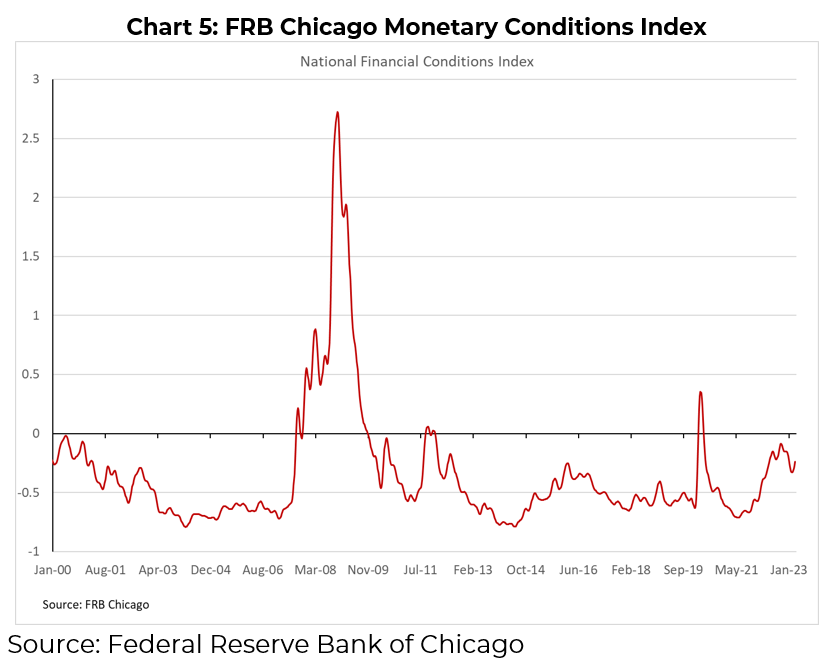

The Fed stance, however, is just less loose, with real interest rates remaining negative (Chart 4) and monetary conditions not yet in the tight region (Chart 5). Moreover, the prior looseness also works with lags and has not played out yet, in my view. We are already beyond secondary and tertiary price increases, and the Fed response is still too weak. Witness the number of labour strikes occurring all over the United States.

The market has already erroneously expected the Fed to stop hiking at least five times only to run into inflation stubbornness and surprises. I expect a few more of these before the US Fed is done and expect the terminal Fed Funds rate to be nearer 6% than 5%. It could very well end up higher if fiscal policy does not change.

The Fed, belatedly, has improved its monetary stance and communication over the last eight months. But unfortunately, overly loose fiscal policy is progressively eroding its ability to control inflation. Therefore, as before, I expect more US Treasury market volatility, more false expectations of a Fed stop, and continued higher interest rates, interrupted by temporary recoveries.

[1] Presentation at the Fundação Getulio Vargas, “Inflation Targeting with Fiscal Fragility,” Aloísio Araujo, March 2023. Based upon the paper Aloísio Araujo, Vitor Costa, Paulo Lins, Rafael Santos, Serge de Valk: “Inflation Targeting with Fiscal Fragility,” Working Paper, 18 December 2022.

[2] Several others found the same effects in G7 countries, especially when adjustment came through expenditure cuts including Giavazzi, F. and M. Pagano, “Can Severe Fiscal Contractions Be Expansionary? Tales of Two Small European Countries,” NBER Macroeconomics Annual, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990): 95–122; and Alberto Alesina (2010): “Fiscal Adjustments: What Do We Know and What Are We Doing?” Working Paper No. 10-61, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, September.

Spring sale - Prime Membership only £3 for 3 months! Get trade ideas and macro insights now

Your subscription has been successfully canceled.

Discount Applied - Your subscription has now updated with Coupon and from next payment Discount will be applied.