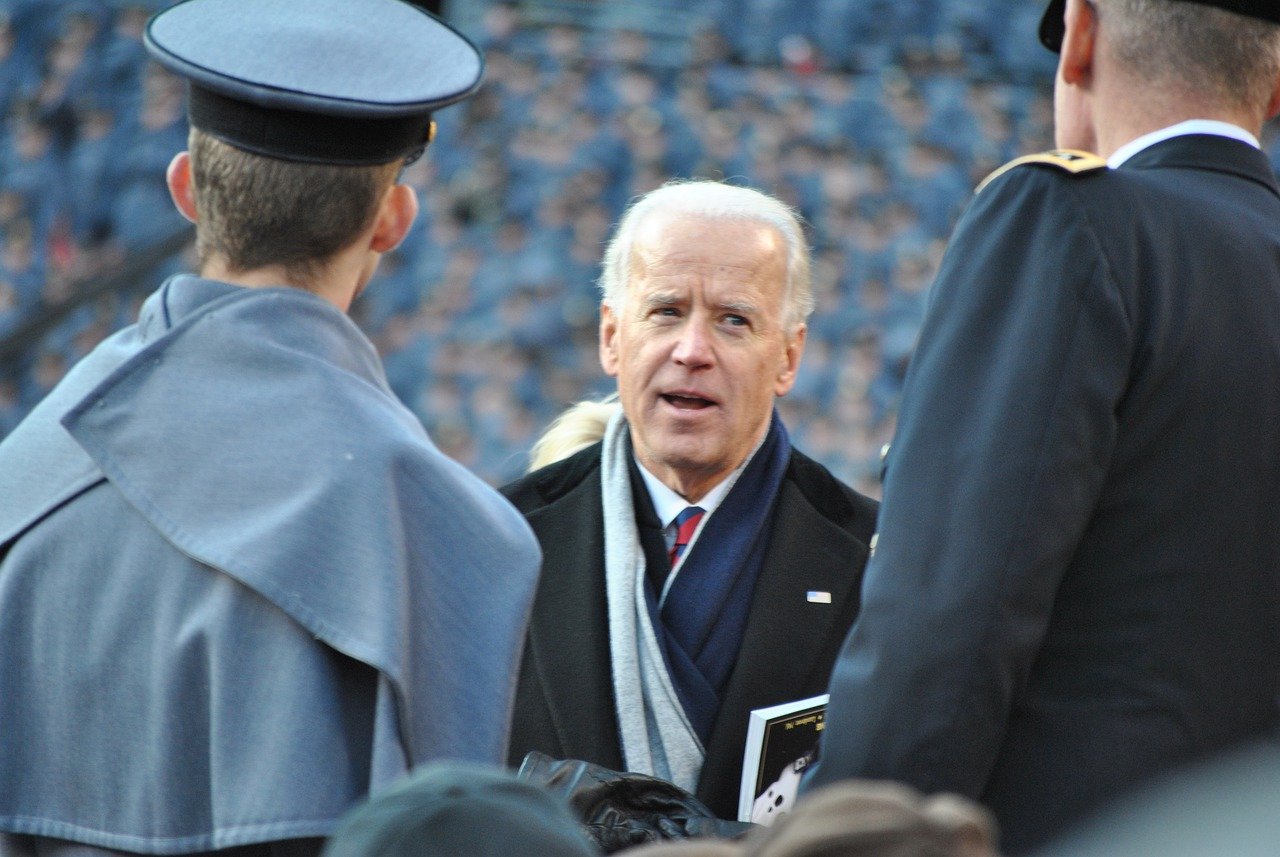

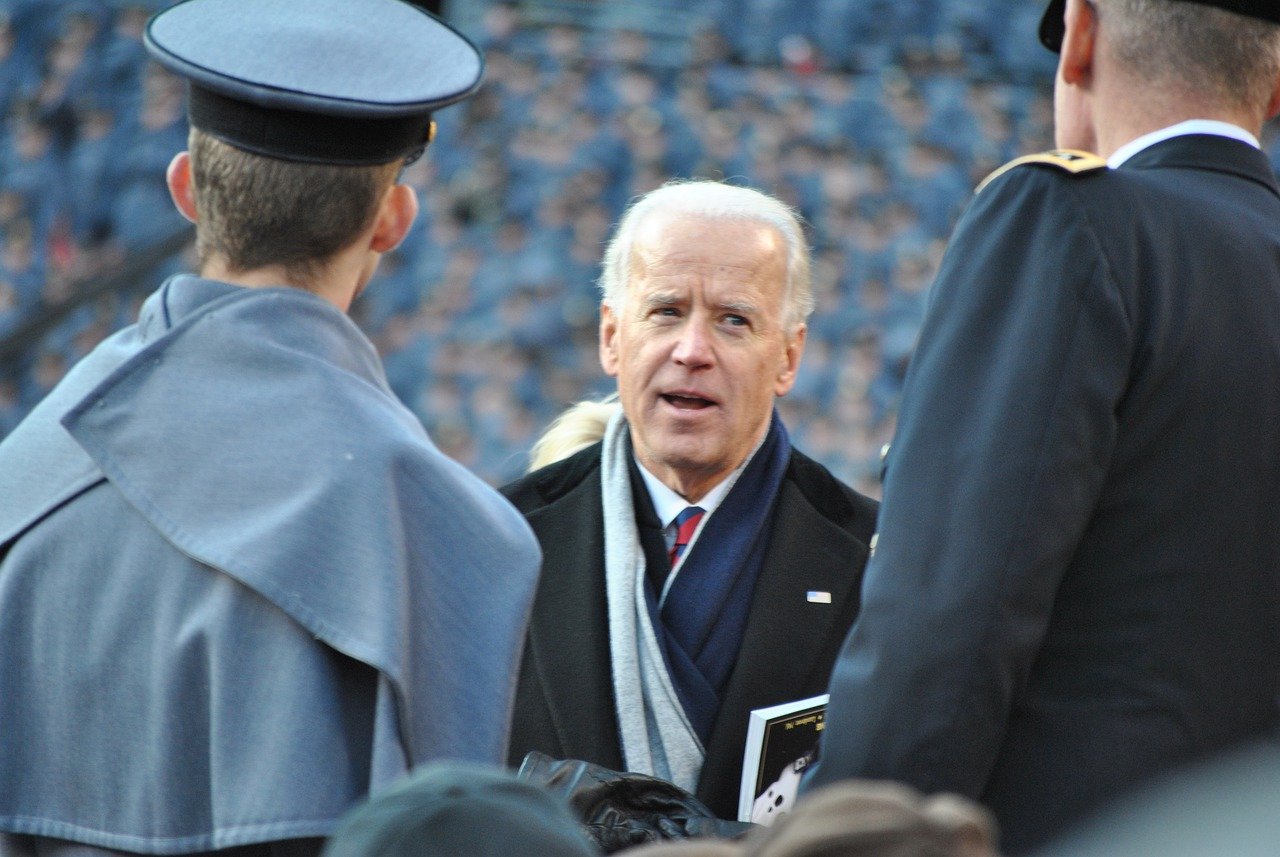

Commentators are drawing several parallels between the opening policy gambits of President Ronald Reagan and President Joe Biden. Both administrations started with large increases in the budget deficit aimed, not just at changing economic policies, but the trajectory of the country. There could be more symmetry than paralleling, though: the Reagan deficits, driven by tax cuts and military spending, started the conservative revolution. By contrast, the Biden deficits, driven by social spending, could begin that revolution’s reversal.

This article is only available to Macro Hive subscribers. Sign-up to receive world-class macro analysis with a daily curated newsletter, podcast, original content from award-winning researchers, cross market strategy, equity insights, trade ideas, crypto flow frameworks, academic paper summaries, explanation and analysis of market-moving events, community investor chat room, and more.

Summary

- As Reagan’s did, Biden’s budget deficits aim to change the trajectory of US society – just in the opposite direction.

- Policy settings are looser and more sustainable under Biden than Reagan.

Market Implications

- Less upside to yields and the dollar, but a steeper curve and rising real rates compared with the Reagan administration.

Reagan’s and Biden’s Gambits

Commentators are drawing several parallels between the opening policy gambits of President Ronald Reagan and President Joe Biden. Both administrations started with large increases in the budget deficit aimed, not just at changing economic policies, but the trajectory of the country. There could be more symmetry than paralleling, though: the Reagan deficits, driven by tax cuts and military spending, started the conservative revolution. By contrast, the Biden deficits, driven by social spending, could begin that revolution’s reversal.

Looser, More Sustainable Policies Under Biden

The economic policy backdrop to both revolutions is very different. First, the deficit is much larger now: close to 15% of GDP in 2021 compared with 4.5% in 1985 (Table 1). But the macro backdrop today is much more supportive of large fiscal deficits than under Reagan, with rates much lower. In turn, these lower rates reflect several factors including lower trend GDP growth and inflation, a structural increase in the demand for safe assets post-GFC, and negative rates in several jurisdictions that suggest global excess savings inexistent under Reagan.

This backdrop suggests much less pressure to implement fiscal consolidation today. By contrast, the Reagan tax cuts preceded a series of gradual tax increases that, by 1992, had fully reversed the impact of the 1981 tax cuts.

Similarly, monetary policy is also easier under Biden than Reagan. In 1981-82, Chair Volcker fixed the quantity of money and let rates soar to lower inflation. Now, the Fed is trying to raise US inflation against a backdrop of deep, global disinflationary trends.

Also, after decades of disinflation and falling inflation expectations, possibly because the Reagan revolution was too successful, the zero bound is increasingly constraining Fed policy. Asset purchases have become, for now, the Fed’s de facto main policy instrument to support the economy. These also happen to help fund the budget deficit, in what Vice Chair Richard Clarida might call a ‘copacetic coincidence’.

Market Consequences

The market consequences are therefore different under the Biden and Reagan revolutions. Due to the Reagan revolution, yields and the dollar soared in the mid-1980s before returning to their pre-Reagan level in the late 1980s. And since then, yields have consistently trended down.

Today, the upside to nominal yields is much more limited, per the factors listed above. Yet there could be significant upside to real yields as inflation expectations adjust more slowly than nominal yields to the improved outlook. Also, the curve could get steeper this time due to the change in the Fed framework, with average inflation targeting (AIT) anchoring the curve’s short end and pulling up the long end through its impact on inflation expectations. That is, once AIT becomes credible.

There is also the perennial question of whether the four-decade-long bull bond market has ended. I cautiously answer ‘yes’, based on the Biden political revolution strengthening workers’ market power, which could steepen the Phillips curve and reduce income inequalities. I believe these structural changes could lift both growth and inflation trends. This, however, is a multi-year process and would require the Democrats to retain control of Congress in 2022 – by no means a done deal.

In terms of the dollar, an appreciation on the scale of the mid-1980s seems highly unlikely. Yet some appreciation is probable because the US is first to emerge from the pandemic. This is due to stronger fiscal policies but also the ‘grassroots normalization’ visible in the surging US mobility indicators. Compare that with Europe’s renewed lockdowns and vaccine fumbles. The US front-runner status suggests a bigger US current account deficit but also bigger bond and equity flows into the US.

A significant difference from the 1980s, though, is that the Fed knows the US economy depends much more on global demand than under Reagan. When deciding its policy stance, the Fed will therefore likely account for negative spillbacks into the US from tighter global dollar funding conditions. This could limit downside risks for EM FX.

For equities, market performance under Reagan will be hard to match. By his presidency’s end, the stock market was up 250% relative to its 1982 nadir during the Volcker recession. I still expect about 5-10% more to the SPX by year-end because, in my view, the strong, noninflationary recovery is not yet priced in.

After 2021, further gains could get more difficult. This is because the factors supporting equity market performance up to now (negative real yields, low inflation, high profits, and high income inequality) could reverse over the next few years. Also, the rebalancing of the policy mix towards fiscal policy suggests more Treasury issuance and a weaker Fed put.

Dominique Dwor-Frecaut is a macro strategist based in Southern California. She has worked on EM and DMs at hedge funds, on the sell side, the NY Fed , the IMF and the World Bank. She publishes the blog Macro Sis that discusses the drivers of macro returns.

(The commentary contained in the above article does not constitute an offer or a solicitation, or a recommendation to implement or liquidate an investment or to carry out any other transaction. It should not be used as a basis for any investment decision or other decision. Any investment decision should be based on appropriate professional advice specific to your needs.)